4. In Search of a Profound Stillness with Agnes Martin and John Zorn

Agnes Martin, Falling Blue (1963)

In his book Human, all too Human (Cambridge University Press, 1986), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) wrote:

Without Melody: There are people who repose so steadily within themselves and whose capacities are balanced with one another so harmoniously that any activity directed towards a goal is repugnant to them. They are like music which consists of nothing but long drawn out harmonious chords, without even the beginning of a moving, articulated melody making an appearance. Any movement from without only serves to settle the barque into a new equilibrium on the lake of harmonious euphony. Modern men usually grow extremely impatient when confronted by such natures, which become nothing without our being able to say that they are nothing. But in certain moods the sight of them prompts the unusual question: why melody at all? Why does the quiet reflection of life in a deep lake not suffice us? – The middle ages were richer in such natures than our age is. How seldom do we now encounter one able to live thus happily and peaceably with himself even in the turmoil of life, saying to himself with Goethe: “the best is the profound stillness towards the world in which I live and grow, and win for myself what they cannot take away from me with fire and sword.” (aphorism 626, translated by Hollingdale)

Friedrich Nietzsche

Most of us long for melody in music. Melody is one of those factors of music that enable the music to say something to us. It is often through melody that music can appear to us as, to use Roger Scruton’s phrase, an “image of the subject”: a free subject, moving according to its own laws, unencumbered by the necessities that undermine so much of our freedom in life. This subjectivity can be expressed in melody so well because the line of a melody, with its metaphorical risings, fallings, and so on, can imitate human action as it works towards a goal. When you add rhythm and harmony you can establish a world in which the journey takes place and one that can provide an ideal analogue against which we can understand and evaluate our own less ideal efforts.

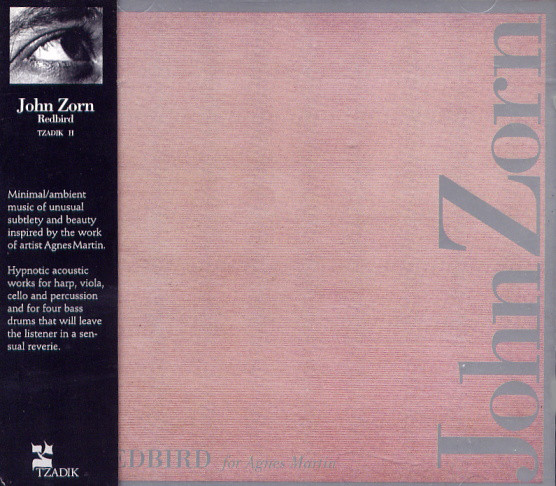

But what if we take away melody? Can we still have an image of the subject? Many would say it is difficult to see how. Perhaps rhythm would help. But what if we take away all or most rhythm and leave only chords? Some minimalist works are indeed primarily chords such as Peter Garland’s solo piano works Two Persian Miniatures I (1971), A Song (1971), and The Fall of Quang Tri (1972). John Cage’s One 8 (1991) is almost 45 minutes of mostly chords played on a cello. But one of my favorite examples is John Zorn’s profoundly moving work Redbird (Tzadik, 1995), inspired by the painter Agnes Martin, which is “a hypnotic work for harp, violin, cello and percussion mirrors the detailed and complex painting for which it is named, as a series of chords are ordered and reordered, creating a play of memory and surprise that will leave the listener in a sensual reverie” (for more info on the piece go to the Tzadik site here).

Zorn’s CD Redbird; the cover is Agnes Martin’s painting Redbird

One way to account for the minimalist power of Redbird (and other works similar to it like those by Morton Feldman) is given in the Nietzsche quotation above: instead of providing an image of a subject directed toward goals amidst the turmoil of life, we have an affirmation of the self as a “deep lake” marked by equilibrium, reflection, and peace. It is interesting to note that Martin has a work Dark River (see below) and Zorn’s recording includes a work for four bass drums by the same name dedicated to her as well. These titles resonate nicely with Nietzsche’s lake metaphor. All these works invite us to transcend our modern impatience and enter into the still depths of our being or, perhaps, reach what Clive Bell in his book Art referred to as a rarified “aesthetic emotion” found on the “cold, white peaks of art” far away from the “snug foothills of warm humanity.”

Martin in her studio, 1954

Now it is certainly true that many artists associated with the minimalist movement employed serial methods of composition in order to remove traces of the world beyond the paint and canvas. They were designed not to refer to, imitate, or represent anything. For example, the painter Frank Stella, commenting on his painting The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II (1959), asserted “What you see is what you see.” And Robert Morris, commenting on his work Two Columns (1961), said his work was an “essentially empty” sculpture with “nothing to say.” But Agnes Martin was trying, through the minimalism of her work, to offer an experience of sublime transcendence. And I think Zorn’s work offers a satisfying musical analogue of this transcendence. Rather than negating transcendent meaning through repetitions, the minimalist gestures of Zorn and Martin seem to enhance it. They seem to offer us an autonomous world apart from our own which, despite its formal limitations, opens up an inexhaustible well-spring. We find, as Harold Budd so nicely put it in the liner notes to his classic ambient album with Brian Eno The Plateaux of Mirror (1980), “a complete world within the confines of a closed cell. That, incidentally, is my definition of minimalism.” And this inexhaustibility would allow them to satisfy a necessary condition for a beautiful thing according to Immanuel Kant, namely, that it always be new to us. When we are immersed in such closed yet vitalizing worlds we may very well experience a profound stillness which cannot, as Goethe said above, be taken away from us with fire and sword. And this stillness can, when we return to our noisy world of time and turmoil, help us remain centered and sane.

Agnes Martin, The Dark River (1961)

For my post on Clive Bell, go here.

For my post on sublime minimalist art, go here.

For my post on the Kantian sublime, go here

For my post which argues that music may be alive, go here.

For my post on demonic music, go here.

For my post on Nietzsche’s insights into musical consistency and personality, go here.

I’ve never thought about any of these things in this way..Really love this, thanks!!

You’re welcome! I am glad you enjoyed the post.