159. An Overview of the Kantian Sublime

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

Introduction

We sometimes refer to experiences, things, and even people as sublime. In doing so we try to convey something exalted, overwhelming, astonishing, and even infinite about them. We may also try and express feelings of delight and terror in their presence. William Wordsworth, in lines 556-572 of his poem The Prelude (Book VI), describes a sublime experience which suggests such feelings:

The immeasurable height

Of woods decaying, never to be decayed,

The stationary blasts of waterfalls,

And every where along the hollow rent

Winds thwarting winds, bewildered and forlorn,

The torrents shooting from the clear blue sky,

The rocks that muttered close upon our ears,

Black drizzling crags that spake by the way-side

As if a voice were in them, the sick sight

And giddy prospect of the raving stream,

The unfettered clouds and region of the heavens,

Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree,

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first and last, and midst, and without end.

Oswald Achenbach, Moonlit Alpine Landscape (1827)

In 1688 John Dennis wrote a letter which explicitly expresses the delightful terror he felt among the Alps:

“We entered into Savoy in the Morning, and past over Mount Aiguebellette. The ascent was the more easie, because it wound about the Mountain. But as soon as we had conquer’d one half of it, the unusual heighth in which we found our selves, the impending Rock that hung over us, the dreadful Depth of the Precipice, and the Torrent that roar’d at the bottom, gave us such a view as was altogether new and amazing. On the other side of that Torrent, was a Mountain that equall’d ours, about the distance of thirty Yards from us. Its craggy Clifts, which we half discern’d, thro the misty gloom of the Clouds that surrounded them, sometimes gave us a horrid Prospect. And sometimes its face appear’d Smooth and Beautiful as the most even and fruitful Vallies. So different from themselves were the different parts of it: In the very same place Nature was seen Severe and Wanton. In the mean time we walk’d upon the very brink, in a literal sense, of Destruction; one Stumble, and both Life and Carcass had been at once destroy’d. The sense of all this produc’d different emotions in me, viz. a delightful Horrour, a terrible Joy, and at the same time, that I was infinitely, pleas’d I trembled.”

And we can think of plenty of other examples, like the sea or the stars, that invoke this delightful terror due to their vast size and might. But how can we make sense of this dual aspect of the sublime?

One plausible explanation came from Edmund Burke in his book A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). In Part I, Section VII (read it here) he writes:

“Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling….When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience.”

Edmund Burke (1729-1797)

So terrible things can be delightful if experienced at a safe distance. But he also points out that this delight is a function of physiological and emotion stimulation. In Part IV, Section VI he notes that “Melancholy, dejection, despair, and often self-murder, is the consequence of the gloomy view we take of things in this relaxed state of body. The best remedy for all these evils is exercise or labor; and labor is a surmounting of difficulties, an exertion of the contracting power of the muscles; and as such resembles pain, which consists in tension or contraction, in everything but degree.” He then claims that sublime stimuli cause physical contractions and tensions which generate emotions that, in clearing “the [bodily] parts, whether fine or gross, of a dangerous and troublesome incumbrance,” are “capable of producing delight; not pleasure, but a sort of delightful horror, a sort of tranquillity tinged with terror; which, as it belongs to self-preservation, is one of the strongest of all the passions.” So a sublime object can, if we experience it at a safe distance, give us a delightful increase of bodily strength inseparable from a memory of the terror it caused.

Burke’s physiologically-based account is certainly plausible and can be seen as a forerunner to contemporary neuroesthetics which tries to understand aesthetic experience at the neurological level. However, Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790), was able to build upon and expand Burke’s insights to provide an equally influential and yet far more interesting theory of delightful terror. In this essay I give an overview of the two forms of the sublime he discusses in sections 25-28 of his book, namely, the mathematical and the dynamic (you can read the sections as well as the whole book here). We will see how Kant’s theory has far reaching consequences for aesthetics, metaphysics, morality, religion, and culture. We will also see how his account raises plenty of questions and concerns which can help us critically probe the depths of this fascinating yet elusive aesthetic category. Let’s begin with some preliminary ideas and distinctions that can be approached by way of a comparison with his account of beauty.

Some Preliminary Ideas and Distinctions

Kant claims that judgments of the sublime, like judgments of the beautiful, are (1) aesthetic which means they are based on our feelings of pleasure and pain in response to certain things; (2) reflective rather than determinate judgments which means that, rather than starting with a clear concept of something and judging a particular thing to fall under that concept (as we do when we judge a particular shape to be a triangle), we start with a particular thing and then try and find a concept for it; (3) disinterested insofar as we contemplate something for its own sake and not for its use value, truth value, or moral value; (4) universal because our feelings led us to assert that everyone should agree with our judgments even if they do not; and (5) necessary that they should agree since these judgments are grounded in the innate capacities common to all humans.

However, judgments of the sublime differ from judgments of the beautiful in a variety of ways. Here are a few:

(1) Kant states that the “beautiful in nature concerns the form of the object, which consists in [the object’s] being bounded. But the sublime can also be found in a formless object, insofar as we present unboundedness, either [as] in the object or because the object prompts us to present it, while yet we add to this unboundedness the thought of its totality.” This unbounded formlessness differentiates the sublime from the beautiful that exemplifies bounded form.

(2) Judgments of beauty reveal that there is something beautiful in the object: some formal properties that trigger what Kant refers to as a “free play of the imagination.” But Kant startles us by claiming that judgments of the sublime are completely about our minds: “We hence see also that true sublimity must be sought only in the mind of the subject judging, not in the natural object the judgment upon which occasions this state. Who would call sublime, e.g., shapeless mountain masses piled in wild disorder upon one another with their pyramids of ice, or the gloomy, raging sea?” So the unboundedness of a raging sea is not, technically, sublime; rather, it just serves as an occasion for us to experience the sublime within ourselves. Kant doesn’t expect that everyone will know the true grounds of the sublime. He knows that many will mistakenly attribute the sublime to something external rather than internal. Kant calls this mistake “subreption.” But we can come to understand the true grounds of the sublime if we reflect carefully on the conditions for the possibility of having sublime experiences.

Karl Eduard Biermann, The Wetterhorn (1830) Kant: there is nothing sublime about those ice-covered peaks!

(3) Judgments of beauty are marked by “purposiveness” insofar as we feel that our imagination and understanding are made for the form it enjoys. Beauty makes us feel at home in nature which is experienced as amenable to our faculties. But sublime experiences, while they do eventually bring us pleasure, at first give rise to displeasure and even terror when we realize that we can’t adequately represent and/or resist nature. We do not feel at home in the world and experience “contrapurposiveness” or a disconnect between our faculties and nature.

Now let’s turn to Kant’s two forms of the sublime. In doing so we can explore some of the above concepts and distinctions in more detail.

The Mathematical Sublime

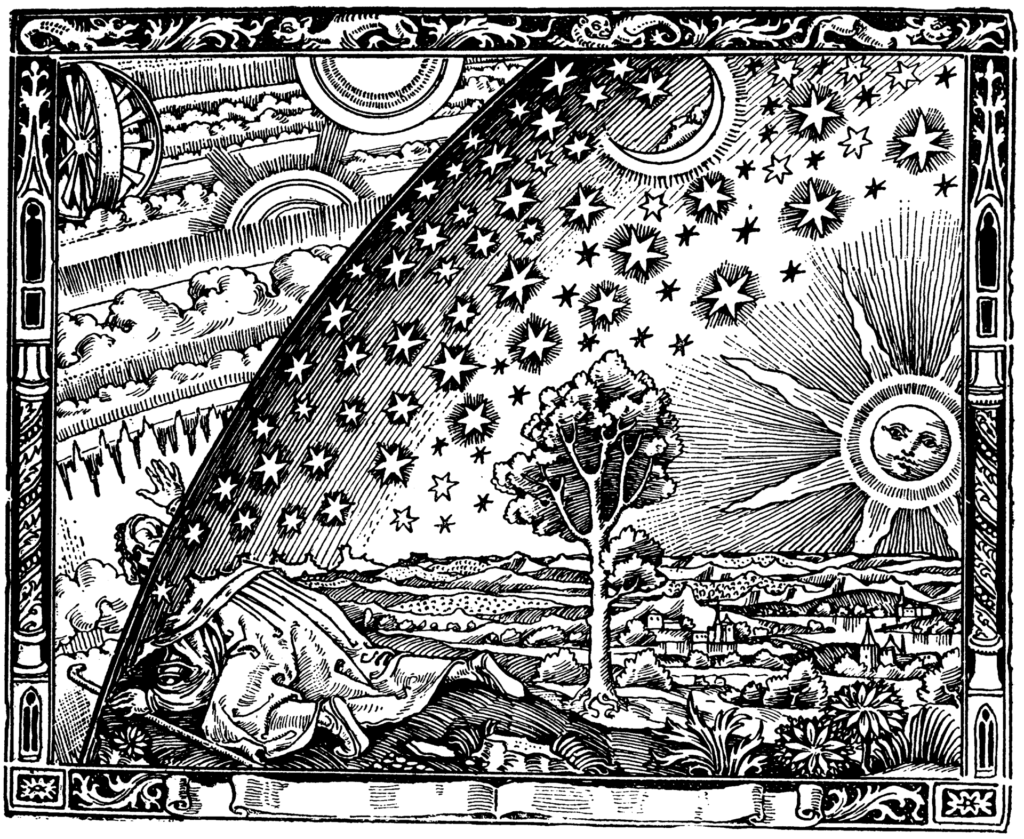

In an experience of the mathematical sublime we perceive something to be boundless in numerical extent or spatial extension, say the starry heavens with its seemingly infinite number of stars, which triggers our reason, which is our “ability to seek and find unity and completeness among concepts and principles themselves,” to demand that our imagination represent the boundless expanse. Our imagination “strives to progress towards infinity” in order to find a standard of measure appropriate to the boundless magnitude. And this standard must be “aesthetic” or one which enables it to represent the boundlessness “by the eye” in a unified “comprehension.” But in the mathematical sublime there is a limit to what we can take in all at once and we fail to capture boundlessness in a bounded representation. Thus “in the immensity of nature, and in the inadequacy of our faculties for adopting a standard proportionate to the aesthetical estimation of the magnitude of its realm, we find our own limitation.”

As a result,

(1) we experience displeasure when we realize there are things we can’t get our imaginations around. This realization makes us feel profoundly alienated and diminished in the presence of that which we are experiencing. Indeed, Kant notes that the task of imagining the infinite “is for the Imagination like an abyss in which it fears to lose itself.” Blaise Pascal, in section 72 of his Pensées (1670), beautifully expressed this abyss that can unveil our insignificance: “For in fact what is man in nature? A Nothing in comparison with the Infinite, an All in comparison with the Nothing, a mean between nothing and everything. Since he is infinitely removed from comprehending the extremes, the end of things and their beginning are hopelessly hidden from him in an impenetrable secret, he is equally incapable of seeing the Nothing from which he was made, and the Infinite in which he is swallowed up.”

But then

(2) this inability makes us aware that our reason can think, rather than imagine, “infinity as a whole” which is “absolutely large” or “large beyond all comparison.” This thought is the mathematical sublime and it gives us a feeling of pleasure. And it is the condition for the possibility of our imagination’s failure. After all, if we didn’t have the idea of infinity as a whole we wouldn’t know what the imagination is falling short of. Think of what it means to fail in a sport, in school, or in a career: in all these cases we know what it means to fail because we know what it means to succeed. Something similar is happening with the mathematical sublime: we must be able to think infinity if we are to experience the failure of our imagination to represent it.

Thus the stars (or any other similar phenomena of astonishing magnitude) are not sublime. But they help us experience what IS sublime, namely, THE IDEA OF INFINITY AS A WHOLE.

Kant likens the dynamic struggle between imagination and reason to a “vibration, i.e., to a rapidly alternating repulsion from, and attraction to, one and the same object.” It is this struggle which, insofar as it includes both pleasure and displeasure, allows him to account for the delightful terror of the mathematical sublime. Our victory in this struggle, our grasping of the idea of infinity as a totality, allows us to see how our reason has a “supersensible” power which transcends our finite human bodies in space and time. Without this power we wouldn’t experience the sublime in the first place. Kant expresses this when he notes that the “Sublime is what even to be able to think proves that the mind has a power surpassing any standard of sense.”

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Life (2011; room with mirror, LED lights, water pool)

Thus it appears Kant is putting forth a transcendental argument or an argument that reasons from the experience of something to the condition(s) necessary for the possibility of having that experience. In this case, he is beginning with our aesthetic experience and inferring what makes that experience possible, namely our supersensible capacity to think infinity as a whole. This argument can be formalized as follows:

Premise 1: In the face of certain phenomena which appear boundless in number and/or spatial extent we experience, on the one hand, the painful failure of our imagination which makes us feel diminished to nothing and, on the other hand, the subsequent pleasure of feeling exalted above that which appears to diminish us.

Premise 2: If our reason didn’t have a supersensible capacity to think the idea of infinity as a whole then we wouldn’t feel pain (there would be no idea of infinity as a whole for the imagination to fall short of) nor would we have any pleasure (the idea of infinity as a whole would be inaccessible to us).

Conclusion: Therefore our possession of the supersensible idea of infinity as a whole is the condition for the possibility of having an aesthetic experience of the mathematical sublime.

Kant’s inclusion of infinity and supersensibility shows how different his account is from Burke’s physiological approach. And we can see another difference when we see that this capacity for surpassing our finitude in the mathematical sublime, far from just vitalizing us physiologically, actually exalts and dignifies us. Robert Doran, in his book The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant (Cambridge, 2015), explains how:

“In this idea of “superiority over nature,” what one could call Kant’s heroic vision of the human being as self-transcending and self-exalting comes to the fore. The experience of sublimity demonstrates that human greatness is superior to natural greatness – that human greatness alone is absolute. In our struggle with nature in its inhospitable aspects (in this case its immeasurability), which exposes the limits of our sensible nature (our inability to provide a sensible standard for certain magnitudes), the mind’s encounter with the seemingly absolute greatness of nature becomes an image of its own absolute grandeur. The attempt to grasp the immeasurable in nature can thus be seen as a kind of challenge or duel, in which the seemingly inferior party discovers itself to be superior – hence the paradox of being exalted by being overwhelmed.” (226-227)

Rather than feeling insignificant in the face of the stars, we realize we have a rational capacity that makes us greater than the stars since the stars, despite their vastness, are finite: “Thus in our mind we find a superiority to nature even in its immensity.” Indeed, the stars are small in comparison to the infinity of the mathematical sublime: “That is sublime in comparison with which everything else is small.” And we should note that, while our imagination does experience a humiliating defeat in one way, in another way it is liberated by being expanded to the very brink of an abyss: “For though the imagination, no doubt, finds nothing beyond the sensible world to which it can lay hold, still this thrusting aside of the sensible barriers gives it a feeling of being unbounded; and that removal is thus a presentation of the infinite. As such it can never be anything more than a negative presentation—but still it expands the soul.”

The Milky Way photographed by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope

But we must keep in mind that infinity as a whole cannot be represented as a bounded image nor can it be empirically (through sense experience) demonstrated in the limits of space and time. As Kant says in his Critique of Pure Reason: “Any such magnitude, as being that of a given infinitude is empirically impossible, and, therefore, in reference to the world as an object of the senses, also absolutely impossible.” We can only represent or demonstrate potential infinities or sequences which, while having no end point, do not exist as finished or actual infinities. Thus there can be no scientific demonstration of the mathematical sublime. But aesthetic experience allows us to directly feel it and rationally infer its transcendent existence.

Before moving on to the dynamic sublime I would like to share an experience I had that seemed to exemplify the mathematical sublime. I was on a plane leaving Japan when I witnessed an astonishing merging of sea and sky upon which a few white boats sailed. This picture captures a taste of the vision which, from my view in the plane, had no discernible limits:

Pacific Sublime (copyright Dwight Goodyear)

This vision of boundless blue, with its boundless ripples that gradually disappeared into boundless folds of clouds, caused me to suddenly lose my depth perception. I couldn’t tell where the sea ended and the sky began. Everything merged into a shimmering two-dimensional expanse which defeated my imagination. But I took great pleasure in contemplating it at length and felt what might be called a vertigo of the infinite.

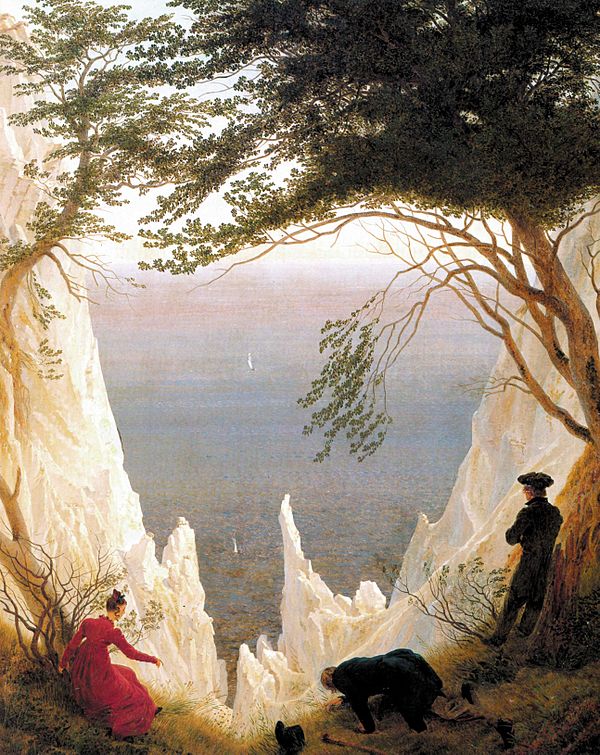

I was later pleased to see that a similar merging of sky and sea with tiny white boats was captured by Friedrich. I like to think the man on the right, who appears to be in a state of disinterested contemplation rather than curiosity (the woman) or fear (the man on the ground), is experiencing the mathematical sublime as well:

Caspar David Friedrich, Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (1818)

The Dynamic Sublime

In an experience of the dynamic sublime we experience something not boundless in magnitude as in the mathematical sublime but boundless in might that threatens to destroy us. But this might must be perceived in a safe and disinterested manner which removes it from any survival imperative: “He who fears can form no judgement about the Sublime in nature; just as he who is seduced by inclination and appetite can form no judgement about the Beautiful. The former flies from the sight of an object which inspires him with awe; and it is impossible to find satisfaction in a terror that is seriously felt.” Kant offers some examples of the sublime in nature: “Bold, overhanging, and, as it were, threatening rocks, thunderclouds piled up the vault of heaven, borne along with flashes and peals, volcanoes in all their violence of destruction, hurricanes leaving desolation in their track, the boundless ocean rising with rebellious force, the high waterfall of some mighty river, and the like, make our power of resistance of trifling moment in comparison with their might.”

John Martin, The Great Day of His Wrath (circa 1851)

Such experiences trigger us to imagine successful resistance to this might. In doing so we

(1) experience imaginary fear when we can’t imagine how, as human bodies, we can resist the seemingly boundless might.

But then

(2) we imagine ourselves courageously resisting nonetheless. This form of imaginary resistance makes us aware that we can transcend our physical fear and respond as free persons rather than determined bodies. And this capacity for free, independent action is the dynamic sublime. Our experience of this capacity produces a feeling of self-esteem that replaces fear. Indeed, this capacity is the condition for the possibility of such esteem since without it we would be left with the despair of inevitable physical destruction.

Thus the mighty forces of nature or man are not sublime. But they help us experience what IS sublime, namely, OUR CAPACITY FOR FREE, INDEPENDENT ACTION.

Philip James de Loutherbourg, Storm and Avalanche near the Scheidegg in the Valley of Lauterbrunnen (1804) Can you imagine yourself doing what the figures on the right appear to be doing, namely, freely choosing to face nature’s power to help another?

Kant puts it this way: “The irresistibility of the might of nature gives us to recognize our physical helplessness, considered as creatures of nature, but at the same time reveals ourselves as independent of it and a superiority over nature on which is founded self-preservation of quite another kind than that which may be attacked and brought into danger by the nature outside us, one where the humanity in our own person remains undefeated.”

So again we see we have a “vibration”: not between pleasure and displeasure (terms Kant uses only with the mathematical sublime although these terms seem to apply here as well) but between fearfulness and self-esteem. It is this struggle which allows him to account for the delightful terror of the dynamic sublime. Our victory in this struggle, our awareness of ourselves as free, allows us to see another way in which our reason has a “supersensible” aspect which transcends our finite bodies in space and time.

Again, I think Kant can be interpreted as presenting a transcendental argument which shows how the idea of the dynamic sublime, the idea of our freedom, must be presupposed if we are to make sense of our aesthetic experience. He writes: “Sublimity, therefore, does not reside in anything of nature, but only in our mind, in so far as we can become conscious that we are superior to nature within, and therefore also to nature without us (so far as it influences us). Everything that excites this feeling in us, e.g. the might of nature which calls forth our forces, is called then (although improperly) sublime. Only by supposing this Idea in ourselves, and in reference to it, are we capable of attaining to the Idea of the sublimity of that Being [my italics], which produces respect in us, not merely by the might that it displays in nature, but rather by means of the faculty which resides in us of judging it fearlessly and of regarding our destination as sublime in respect of it.” This argument can be formulated as follows:

Premise 1: In the face of boundless physical might we experience, on the one hand, the fearful failure of our imagination to create an image of successful bodily resistance and, on the other hand, the self-esteem that comes with the realization that we can courageously resist such might no matter what the consequences.

Premise 2: If we didn’t have free will or a supersensible independence from physical nature then we would only admit defeat and would never experience the self-esteem which the awareness of our independence includes.

Conclusion: Therefore the possession of free will or the ability to act independently of nature is the condition for the possibility of having an aesthetic experience of the dynamic sublime.

Again, this inclusion of radical independence takes us far past Burke’s experience of physical strength and safety. And here, too, we see a moral implication that distinguishes Kant’s approach since the freedom revealed in the dynamic sublime is another source of our human dignity which sets our “supersensible vocation”: our ability to be moral agents not determined by the laws of nature and the limits of space and time. For Kant, morality is always a matter of obedience to a moral law that demands, if it is to be objective and not a function of egoism or moral relativism, that we put aside all our selfish inclinations and do our duty to a moral law that applies to all. In the experience of the dynamic sublime we have an aesthetic confirmation of our ability to do this. We see, despite the mighty powers of nature (including those of our bodies), that we can freely act in ways contrary to them and do what is universally right. This doesn’t mean that we will act morally. But it shows us we can. And, as Kant argued, an ought implies a can. This capacity for moral action invites us to live up to perfect ideals of reason rather than forsake ideals or have no means to approximate them.

Jacques Louis David, The Death of Socrates (1787) Socrates: “Anytus and Meletus may kill me, but hurt me they cannot.” – Plato’s Apology

Of course, our free subjectivity cannot, just like our idea of infinity as a whole cannot, be empirically demonstrated in space and time. If we could scientifically verify freedom, then our status as free subjects would be cancelled: we would become physical objects to be seen, analyzed, dissected, publicly verified, and so on. Thus “the inscrutableness of the Idea of Freedom quite cuts it off from any positive presentation” and “does not permit us to cast a glance at any ground of determination external to itself.” But aesthetic experiences of the dynamic sublime allow us to directly feel our freedom and rationally infer its existence.

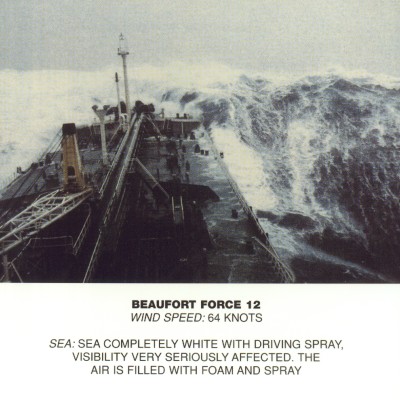

Before moving on I would like to share another experience I had that seemed to exemplify this form of the sublime. It came on a cruise ship which was very close to a hurricane. The turbulent waters and stormy conditions were rocking the ship back and forth, people were getting sick and falling, glass was shattering throughout the ship, and everything on the deck had been cleared. Nonetheless, out of curiosity I went up on the deck to take a look. For the first few minutes I was just taking in the vastness of the ocean and the power of the storm. But then I saw it: a massive wave coming towards the front of the ship as the bow ascended. It looked something like this:

Water spewed forth onto the deck and I felt overwhelming fear. And yet, given the massive size of the boat, I felt just safe enough to appreciate the situation aesthetically. As I watched in astonishment, I remember feeling at peace in the midst of the storm and felt strangely emboldened despite my powerlessness. I realized that, if the hurricane came even closer, my life could be in serious danger. And yet at the moment the prospect of death didn’t seem to matter at all. This revelation revealed a source of power and courage in me that I have been able to draw upon in the face of far less imposing adversaries.

Sublime Culture

Kant makes many interesting observations about the significance of the sublime for culture. His observations suggest that a sublime culture is one in which the two forms of the sublime are made readily accessible to help people develop their human dignity and moral fortitude. This is especially important during times of peace in which a “spirit of commerce” prevails with “selfishness, cowardice, and effeminacy.” Now one might think that a sublime culture would be readily embraced given our shared supersensible moral nature. After all, “Pleasure in the Sublime…presupposes…that of our supersensible destination, which, however obscurely, has a moral foundation.” But Kant goes on to express some doubt: “But that other men will take account of it, and will find a satisfaction in the consideration of the wild greatness of nature…I am not absolutely justified in supposing.” Kant’s lack of absolute justification seems to derive from the fact that a sensitivity to the sublime is harder to develop than a sensitivity to the beautiful. As we have seen, experiences of the sublime, unlike experiences of the beautiful which have no struggle at all, include both pain and pleasure. As a result, many will react to the pain involved in sublime experiences in ways that completely forestall aesthetic experience or terminate the aesthetic experience before any pleasure is reached. Moreover, both forms of the sublime, but especially the dynamic sublime, require a lot of our imagination and some people may lack a powerful imagination. Nevertheless, Kant’s view that all humans are moral beings leads him to generously “impute such satisfaction [in the sublime] to every man” which can be “prepared through culture” and “the development of moral ideas” like the ideas of participating in something transcendent and supersensible, being free, having access to an objective moral law, not being determined by selfish motives and base needs, and so on. Interestingly, Kant’s insights serve as a loose criterion for critiquing aspects of our cultures that are not facilitating these ideas or, what is worse, doing quite a bit to undermine them.

Some Guides to Sublime Experiences

But how can we extend this satisfaction of the sublime through culture? Perhaps the best answer is this: develop practices and institutions that help people experience the magnitude and might of nature. F.W.J. Schelling, in his 1801 lectures on art compiled in the book The Philosophy of Art (Minnesota, 1989), observes that “moral and intellectual flaccidity, weakness, and cowardice of disposition invariably shy away from these great perspectives [of the sublime] that hold up to them a terrible image of their own nothingness and contemptibility.” Nonetheless, he goes on to assert that experiencing the sublime with the help of nature is the best means to overcoming an aversion to the sublime!

“In an age of petty resolve and crippled sensibility I doubt one could find a more appropriate means of preserving and cleansing oneself from such pettiness than such acquaintance with the greatness of nature. I doubt also that there is a richer source of great thoughts and heroic resolve than the ever renewed pleasure in the vision of that which is concretely and physically terrible and great” (87).

Friedrich Schiller, in his essay On the Sublime (1793), agrees: “Who can tell how many luminous ideas, how many heroic resolutions, which would never have been conceived in the dark study of the imprisoned man of science, nor in the saloons where the people of society elbow each other, have been inspired on a sudden during a walk, only by the contact and the generous struggle of the soul with the great spirit of nature? Who knows if it is not owing to a less frequent intercourse with this sublime spirit that we must partially attribute the narrowness of mind so common to the dwellers in towns, always bent under the minutiae which dwarf and wither their soul, whilst the soul of the nomad remains open and free as the firmament beneath which he pitches his tent?”

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) by Ludovike Simanowiz

Schiller also emphasizes the role art can play in the effort to extend the sublime to people: “The sublime, like the beautiful, is spread profusely throughout nature, and the faculty to feel both one and the other has been given to all men; but the germ does not develop equally; it is necessary that art should lend its aid.”

But pointing out that nature and art can help us connect with the sublime is a bit vague. So let’s see if we can clarify these two approaches with some specific tips for distinguishing triggers of the sublime.

Referring to Pyramids at Giza in Egypt, Kant notes “that we must keep from going very near the Pyramids just as much as we keep from going too far from them, in order to get the full emotional effect from their size. For if we are too far away, the parts to be apprehended (the stones lying one over the other) are only obscurely represented, and the representation of them produces no effect upon the aesthetical judgement of the subject. But if we are very near, the eye requires some time to complete the apprehension of the tiers from the bottom up to the apex; and then the first tiers are always partly forgotten before the Imagination has taken in the last, and so the comprehension of them is never complete.”

So this seems to be too far away (photo by Jerome Bonn):

This seems to be too close (photo by Mgiganteus1):

But this would probably be ideal:

So Kant’s tip can help us identify the mathematical sublime in both nature and art.

Paul Crowther, in chapter three of his book How Pictures Complete Us: The Beautiful, the Sublime, and the Divine (Stanford, 2016), offers us four helpful tips to identify both the mathematical and dynamic sublime in art or nature. I list them here and provide a painting after each to exemplify his points:

“Insistent repetition. This occurs when an item’s component elements, or a series of items, present visual rhythms that seem to suggest indefinite continuation beyond the limits of the perceptual field. Here, our sense of what the thing is, is overwhelmed by the challenge to form an image or images of the parts or forms that suggest such indefinite continuation” (60).

John Martin, Pandemonium (1841)

“Insistent and/or complex irregularity or asymmetry, or exaggeratedly large size. Here a familiar kind of vast thing is configured or encountered in a context that deviates from the customary appearance of things of this kind, and thence challenges to consider how this deviation is possible – through attentiveness to the many parts that it involves. But precisely because it is a deviation (is, in some sense, ‘monstrous’) the usual ‘formula’ of the whole does not apply, and thence the parts seem set loose into formless diversification. We cannot form a stable image of the vast whole because principle of its unity has broken down. There is the suggestion of sensory chaos” (60).

John Martin, Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion (1812)

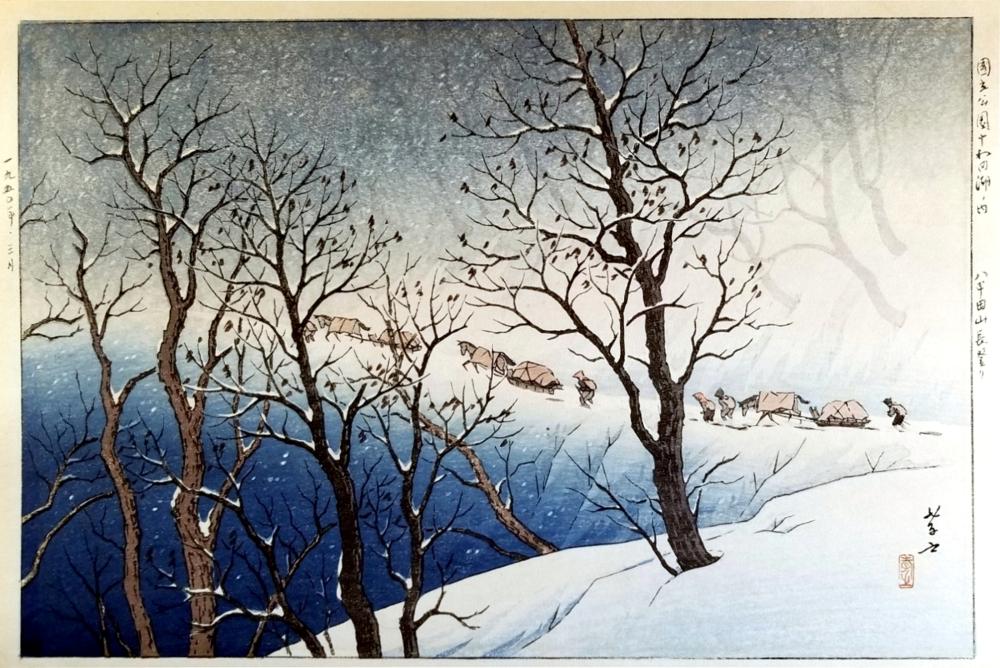

“Animation or the suggestion of it. Very large phenomenal items or states of affairs are usually stationary. When set in motion – as in the case of a stormy sea, or a windswept a forest – the motion of the individual elements, their overlaps, and potential for further motion, attract our perceptual attention. Even static phenomena such as mountains and mountain ranges may set up visual rhythms that challenge us to imaginatively comprehend all the elements that compose the (apparently) animated body” (60).

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840)

“Suggestive concealment. If a large thing is concealed by mist or shadow, this can provoke us to imagine all the parts which are thus hidden. The more visually interesting the idiom of concealment, the more keenly will our imagination try to comprehend the vastness that is so concealed” (61).

John Martin, The Deluge (1834)

Edmund Burke, in part II of his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), discusses many triggers for the sublime as well: privations (e.g., amorphousness, vacuity, darkness, solitude, silence), various degrees of overwhelming power, vast magnitudes in nature or building, perceptions of infinity through repetitions, an awareness of perceptions of difficulty (he uses the example of assembling of Stonehenge but we can easily use the Pyramids at Giza we looked at above), magnificence or the profusion of things that are splendid (he mentions the stars), loud sounds, frightening sounds like the cries of animals, noxious smells and taste, and various images of pain, suffering, and terror. Naturally, we would have to encounter these triggers from a safe distance.

Of course, we need not be confined to visual art. We can explore musical analogues of the above traits (for example, Toshio Hosokawa’s Circulating Ocean, Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victim’s of Hiroshima, and Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes) and literary ones as well such as the above selections from Wordsworth and Dennis or a classic like Edgar Allan Poe’s “Descent into the Maelstrom.” Schiller was convinced that the heroic actions of tragic drama are the best means to experiencing the dynamic sublime. In his essay On the Pathetic he writes:

“Judged from a moral perspective, this action portrays for me the moral law being carried out in complete contradiction of instinct. Judged aesthetically, it portrays to me the moral capability of a human being, independent of all coercion by instinct.”

Schiller’s Kantian interpretation of tragedy also offers one way to resolve the paradox of tragedy, namely, why we enjoy the upsetting events that tragedy depicts: it is painful to see how determined bodies are destroyed by fate but pleasurable to see how fate cannot destroy the moral action of souls. But we need not rely on tragic drama alone. The actual world offers us plenty of examples of people pursuing the good undeterred by physical might. And these examples can be appreciated aesthetically in ways that activate our imagination, invoke the dynamic sublime, and help us become aware of our super sensible moral vocation:

Alabama state troopers attack civil rights demonstrators on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965

“Tank Man” temporarily stopping the advance of a column of tanks on June 5, 1989, in Beijing (photograph by Jeff Widener of The Associated Press)

Lastly, I want to add that the sublime can be accessed intellectually if we study subjects that push our imagination to the limit. This essay itself may be a case in point: studying the sublime philosophically may invoke the sublime! And science offers us many subjects as well. Earlier we saw a photograph of the Milky Way that gives us a sense of the sublime. But perhaps we could just think about a set of facts that pertain to the Milky Way to get that sense as well. Joseph Campbell, in his book The Inner Reaches of Outer Space (New World Library, 2002), offers us just such a set of facts which I quote at length:

“And so now, of all the possible centers, our own earth, of course, is the only one available to us. Revolving on its own axis once every twenty-four hours, this operational still point is annually circling one of the several hundred billion suns that constitute our galaxy, this sun is meanwhile traveling at the rate of 136 miles per second around the periphery of our native galaxy, circling it once every 230 million years. The diameter of this galaxy, this Milky Way of exploding stars, is now described as 1000,000 light years, a light year being the distance light travels in one year. But light travels at the rate of 186,000 miles per second, and the number of seconds in a year (if I calculate correctly) is 31,557,600. So that if we multiply 186,000 miles by 31,557,600 seconds, we arrive at the idea of one light year, which is, namely (if again I calculate correctly), 5 trillion, 869 billion, 713 million, 600 thousand miles. And 100,000 of these will then amount to 586 quadrillion, 971 trillion, 360 billion (586,971,360,000,000,000) miles. And within this galaxy of that diameter, the nearest sun to our sun, nearest star to our star, is Alpha in Centauri, which is about 4 light years, which is to say, a mere 25 trillion miles, away. From our position in this inconceivable galaxy, when we look up at night at the Milky Way, we are sighting, as it were, along the radius of a great disk. The other stars that we see in the night sky are members also of this galaxy, but are situated to one side or the other of the crosscut. And this disk, this galaxy of which our sun is a minor member, is but one of what is know as a “local group” of galaxies, the number in our particular group being twenty: twenty Milky Ways of billions of exploding nuclear furnaces, flying from each other through spaces not to be measured, the universe (of which we speak so easily) comprising, literally, quintillions of such self-consuming stars” (4).

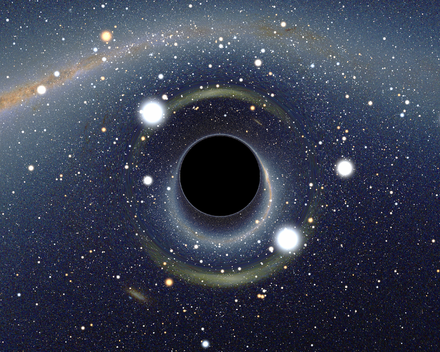

And we could let our thoughts follow facts about black holes into the infinitely small as well: “Given the usual understanding that relativity theory rules out any physical process propagating faster than light, we conclude that not only is light unable to escape from such a body: nothing would be able to escape this gravitational force. That includes the powerful rocket that could escape a Newtonian black hole. Further, once the body has collapsed down to the point where its escape velocity is the speed of light, no physical force whatsoever could prevent the body from continuing to collapse further, for that would be equivalent to accelerating something to speeds beyond that of light. Thus once this critical point of collapse is reached, the body will get ever smaller, more and more dense, without limit” (see the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry “Singularities and Black Holes”).

Simulated view of a black hole in front of the Large Magellanic Cloud by Alain r

So those are some guides for the sublime that we might explore in nature, ideas, human action, and various art forms like painting, music, dance, poetry, theater, cinema, literature, opera, photography, sculpture, and so on. In doing so we might become more attuned to the sublime both individually and collectively for a more sublime culture. To be sure, if people have weak imaginations and deny the existence of moral ideas then these strategies may be far less effective. But Kant stresses that, while the sublime often requires some culture, the sublime is not produced by culture. Thus it can still enter our lives by experience regardless of our conventions and conditioning.

Questions and Concerns

Kant’s account of the sublime is clearly as ingenious as it is influential. As you may have gathered, I am quite sympathetic to it. But it raises plenty of closely connected questions and concerns. Here are a few to generate critical thinking.

(1) Recall Kant’s question: “Who would call sublime, e.g., shapeless mountain masses piled in wild disorder upon one another with their pyramids of ice, or the gloomy, raging sea?” The answer seems clear: a lot of people! So we need to ask: can we really accept Kant’s radical claim that the sublime is, ultimately, just about our reason and not about nature at all? Isn’t it clearly the case that mountains, the sea, the stars, and so on are sublime? At the very least, can’t we have both ideas and objects as sublime? Could it be that John Dennis was right when he observed that the sublime is located in neither mind nor object alone but is a function of both? As he said: “Take the Cause and the Effects together…and you have the Sublime.” Or could it be that the sublime occurs precisely when we are removed from the experience as much as possible? For example, Arthur Schopenhauer, in Vol. 1, section 39 of his The World as Will and Representation, claims that in experiences of the sublime we experience complete defeat as individuals but are exalted as manifestations of one eternal knowing subject. To gain this exaltation, however, we must forget individuality: “This we find ourselves to be [modifications of the one eternal knowing subject], as soon as we forget individuality.” In dealing with these questions a lot will ride on whether we include freedom and infinity in our account of the sublime. For if we do include them then we can readily see how the inclusion of mountains and raging seas, since they are finite and not free, must be excluded. And if we choose to bypass our finite individuality as Schopenhauer prescribes then we may find that the whole logic of personal elevation falls apart since, in the end, we are not elevated but rather the one eternal knowing subject is. And does it make sense to speak of an eternal subject being elevated?

(2) We can also ask: must it be the case that sublime experiences have to include pain, displeasure, terror, and so on? Can’t we experience the exalted states of the sublime without suffering? Rachel Zuckert has shown, in her article “The Associative Sublime: Gerard, James, Alison, and Stewart,” that some theorists of the sublime, such as Alexander Gerard, Lord Kames (Henry Home), Archibald Alison, and Dugald Stewart, described sublime experience as serene and pleasant elevation alone. So why must the sublime be a delightful terror? Can’t this scene captured by Thomas Cole be sublime too? One way to deal with these questions is to readily admit that the sublime is many things to many people and that the Kantian sublime is one in a family of similar, yet different, accounts. Adopting his account to make sense of a particular kind of experience (one that includes both pain and pleasure) need not invalidate other accounts that explore sublime experiences without such extreme contrasts. We might also follow a suggestion made by Paul Crowther who, in his book How Pictures Complete Us: The Beautiful, the Sublime, and the Divine (Stanford, 2016), claims that the sublime doesn’t necessarily require our imagination be overwhelmed; rather, “we can “read off” from our recognition of the appropriate cues” that a certain phenomenon of vast magnitude or might would, if we attended to it, quickly exceed our imagination (70). If this is the case then we could have sublime experiences in accordance with Kant’s model but without the displeasure he emphasizes.

Thomas Cole, The Hunter’s Return (1869)

(3) In this essay I have emphasized romantic-era painting as a means of conveying something about the sublime. But other styles can be employed as well. For example, Barnett Newman’s large (7′ 11 3/8″ x 17′ 9 1/4″) abstract expressionist work Vir Heroicus Sublimis (Man, Heroic and Sublime) from 1951 was meant to convey the sublime. Indeed, Newman’s influential essay ‘The Sublime is Now’ (1948) made a case for non-representational modern art being sublime rather than beautiful in its power to say something that cannot be shown:

And we have already encountered Wordworth’s poetry, Dennis’ prose, and Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Life which show that other mediums can be employed as well. However, many have argued that Kant didn’t think art could convey the sublime. But I think a careful reading of his text shows that he thought it could if (1) its terrible aspects were given a beautiful presentation thus neutralizing their threat and allowing for disinterested contemplation and (2) it allows for an indirect presentation of that which can’t be presented. Obviously, Newman’s painting is not representational and so does seem to point us to something beyond it. But we might argue that all indirect presentation presupposes something substantially direct to transcend…something which modern art like Newman’s my fail to provide. Conversely, some of the romantic works in this essay may be too direct. Perhaps a middle ground is to be sought after. Of course, this whole line of inquiry presupposes that art can express the sublime. Plenty of subsequent and diverse theorists of the sublime, such as Schiller, Schelling, Hegel, Schopenhaur, Nietzsche, Lyotard, and Newman, would agree with Kant that it can. But are they right? And if so, which art forms, if any, are superior in conveying it? Under what conditions can art be best perceived as sublime? Could it be that art is in some way superior to nature as far as conveying the sublime is concerned? If so, why? Or could it be that, despite all the efforts to indirectly present the sublime, only nature really succeeds in doing so?

(4) Must we follow Kant in claiming that sublime judgments are disinterested, that is, made without any concern for morality, truth, or use-value? Isn’t this criteria too restrictive? Isn’t it the case that the contemplative terrors associated with might or magnitude require that we know, for example, that a storm could actually destroy us and that the stars are actually immeasurable? Doesn’t this show that truth is inseparable from judgments of the sublime? I think so. But I don’t think this is a major problem for Kant. For there is a big difference between examining a storm scientifically in order to learn facts about it and experiencing a storm aesthetically in way that is primarily about feeling despite keeping certain facts in mind. Thus I can grasp a truth about something, for example that a wave can destroy me as a physical being, but perceive this thing in a disinterested manner if (1) my purpose is not to examine that truth, connect to other truths, find new truths, and so on and (2) I experience this truth in and through the thing itself for its own sake in a way that is felt.

(5) Are we prepared to accept the metaphysical framework in which Kant embeds his analysis, namely, the distinction between the supersensible or noumenal realm on the one hand and the sensible or phenomenal realm on the other? If not then it is hard to see how can we make sense of the supersensible ideas of freedom and infinity. I myself am sympathetic to dualistic visions of the world and ourselves, so adopting something similar to Kant’s divide is not unacceptable to me (go here for my posts on dualism). But perhaps we can make an effort to account for the feelings involved in the Kantian sublime in a less metaphysical and more naturalistic way. Or perhaps we can adopt a post-modern approach to the sublime which tends to remove the rational exaltation of Kant’s model and just explore the ramifications of the imagination’s failure to present the unpresentable. But whatever the case may be, wrestling with Kant’s highly complex metaphysical baggage is a requirement if we are to take his theory seriously.

(6) Many have pointed out that the Kantian sublime seems to be offering a secular replacement for religion. Like many religions, it shows how we are exalted in some ways and humbled in others. But unlike many religions it appears to offer us transcendence through the rational ideas of infinity and freedom alone: no God needed. But things are a bit more complicated. After all Kant, as Paul Guyer points out in his Kant and the Experience of Freedom (Cambridge, 1996), thought that “God’s creation is humbled before our own free reason and even the sublimity of God himself can be appreciated through the image of our own autonomy” (259). This is, to say the least, no traditional religious narrative! But we do see Kant moving from thoughts about the sublime to thoughts about God in a way that echoes Thomas Burnet in his 1681 book The Sacred Theory of the Earth (Vol. I, Chapter 11):

“The greatest objects of Nature are, methinks, the most pleasing to behold; and next to the great Concave of the Heavens, and those boundless Regions where the Stars inhabit, there is nothing that I look upon with more pleasure than the wide Sea and the Mountains of the Earth. There is something august and stately in the Air of these things that inspires the mind with great thoughts and passions; We do naturally upon such occasions think of God and his greatness, and whatsoever hath but the shadow and appearance of INFINITE, as all things have that are too big for our comprehension, they fill and over-bear the mind with their Excess, and cast it into a pleasing kind of stupor and admiration.”

Moreover, Kant’s Enlightenment agenda to reconcile reason with religion leads him to claim that the sublime freedom we share with God allows us to forge a harmonious relationship that transcends fear: “Only if he is conscious of an upright disposition pleasing to God do those operations of might serve to awaken in him the Idea of the sublimity of this Being, for then he recognises in himself a sublimity of disposition conformable to His will; and thus he is raised above the fear of such operations of nature, which he no longer regards as outbursts of His wrath.” And the importance of aesthetics here is clear: without the disinterested contemplation we find in the sublime we would never be able contemplate God’s greatness: “The man who is actually afraid, because he finds reasons for fear in himself, whilst conscious by his culpable disposition of offending against a Might whose will is irresistible and at the same time just, is not in the frame of mind for admiring the divine greatness. For this a mood of calm contemplation and a quite free judgement are needed.” Those who fear God can only relate to God through interested judgments that preclude contemplation. As a result, they will never come to understand God’s sublime nature. Indeed, they will remain in the grip of “superstition” which is “not reverence for the Sublime, but fear and apprehension of the all-powerful Being to whose will the terrified man sees himself subject, without according Him any high esteem. From this nothing can arise but a seeking of favour, and flattery, instead of a religion which consists in a good life.” Again, Kant’s conception of relating to God without fear and trembling may break from many traditional religious narratives. But it is certainly not a concern you would find in a purely secular account.

We should also note that Kant’s claim that nature has no dominion over us seems to imply the immortality of the soul. William Hund, in his article “The Sublime and God in Kant’s Critique of Judgment,” explains:

“Although Kant did not explicitly state that this ‘self-preservation of quite another kind’ is the immortality of the soul and not merely our moral and intellectual superiority over the brute forces of nature, I think that the context demands this interpretation. For if nature could kill the soul as well as the life of the body, then nature would have dominion over us. But since Kant held that nature has no dominion over us, then it follows that it is because nature cannot kill our soul.”

This implication, along with all the other claims about access to the supersenisble realm in his account, reveal that Kant’s account is far more religious than some think. Of course, it doesn’t follow that his account is explicitly religious. After all, Kant doesn’t quite sound like Joseph Addison who, in the Spectator (1712, No. 413), wrote:

“One of the Final Causes of our Delight, in any thing that is great, may be this. The Supreme Author of our Being has so formed the Soul of Man, that nothing but himself can be its last, adequate, and proper Happiness. Because, therefore, a great Part of our Happiness must arise from the Contemplation of his Being, that he might give our Souls a just Relish of such a Contemplation, he has made them naturally delight in the Apprehension of what is Great or Unlimited.”

Or Blaise Pascal who claimed that “The whole visible world is only an imperceptible atom in the ample bosom of nature. No idea approaches it. We may enlarge our conceptions beyond all imaginable space; we only produce atoms in comparison with the reality of things. It is an infinite sphere, the centre of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. In short it is the greatest sensible mark of the almighty power of God, that imagination loses itself in that thought” (Pensées, section 72).

In light of these tensions, we can ask: is Kant’s account not religious enough? Is it not secular enough? Is it just right?

(7) We have seen that the mathematical and dynamic sublime are supposed to reveal our capacities to act independently of nature and to think infinity as a whole. But could it be that sublime experiences reveal only illusions of independence and infinity? Perhaps a feeling that we are free when, in fact, we are determined or necessitated to act as we do? Perhaps a feeling of thinking actual infinity when we are completely and inescapably finite? These questions help us see one of the problems with transcendental arguments like those we saw above, namely, their inability to exclude other ontological interpretations of the datum from which they start. For example, in this case we begin with the experiences of being both diminished and exalted in the face of immeasurable magnitude and might. These are very visceral and intense experiences which need explaining. Kant then offers us an explanation in terms of necessary conditions: what must be present (the rational ideas of infinity and independence) if we are to have them. But can his arguments exclude other interpretations that, for example, reduce the sublime to neurological factors that have nothing to do with freedom or infinity at all? It is hard to see how. It is not like we can just consider the initial data and see, in a self-evident way, that certain conditions are required. If that was the case we wouldn’t even need a transcendental argument in the first place. But then this means that what is offered as necessary conditions for the data might not be necessary after all. However, Charles Taylor has argued (see here) that what a transcendental argument can do is articulate for us what we must assume if we try and make sense of the initial experience within a certain conceptual framework – in this case, the framework of ourselves as rational beings with reason, imagination, will, understanding, and so on who have aesthetic experiences with unique feelings and make judgments about those experiences that are reflective, universal, and necessary. Given this framework we can see how Kant’s arguments help us peer into it with more depth and articulate an account consistent with it. This is a boon since it is something with which we are intimately familiar and it helps us explain the sublime as it is to us rather than explain our experience away by reducing it to principles inconsistent with independence and infinity.

That said, the general framework in which Kant situates his analysis may be mistaken and so we might want to supplement his transcendental arguments with other insights. Of course, one who has experienced the power of the sublime might find no need to defend this framework against alternative ontological interpretations. After all, why can’t aesthetic experience be enough? Joseph Addison, writing of the “agreeable horror” he experienced when perceiving the “troubled ocean,” claimed that “Such an object naturally raises in my thoughts the idea of an Almighty Being, and convinced me of his existence as much as a metaphysical demonstration” (see Spectator, 489).

Ivan Aivazovsky, Wave (1889)

Couldn’t we say something similar for the rational ideas of infinity and independence? Well, we have seen that Kant didn’t think our feelings of the supersensible and our reflective judgments about them offer us scientific knowledge. But this doesn’t mean they can’t count as some form of knowledge. Consider this passage from R.G. Collingwood’s book The Idea of Nature (Martino, 2014):

“Kant never for a moment thought that the thing in itself was unknowable…The words wissen, Wissenschaft in Kant have the same kind of special or restricted significance that the word ‘science’ has in ordinary modern English. Science is not the same as knowledge in general; it is a special kind or form of knowledge whose proper object is nature and whose proper method of procedure is exactly that combination of perception with thought, sensation with understanding, which Kant has tried to describe in the Aesthetics and Analytics of the Critique of Pure Reason. Kant has not given us a theory of knowledge in the modern sense of the term: what he has given us is a theory of scientific knowledge; and when he said that we could think the thing itself though we could not know it he meant that we had knowledge of it but not scientific knowledge.” (118).

And Rudolf Otto, in his book The Idea of the Holy (Oxford, 1958), makes a few points about feeling and knowing that resonate nicely with Kant’s observation that aesthetic judgments are reflective judgments which, rather than starting from known concepts, seek out concepts. He writes: “Something may be profoundly and intimately known in feeling for the bliss it brings or the agitation it produces, and yet the understanding my find no concept for it. To know and to understand conceptually are two different things, are often even mutually exclusive and contrasted” (135). And: “Kant employs sometimes another expression also to denote such obscure, dim principles of judgment, based on feeling, viz. the phrase ‘not-unfolded’ or ‘unexplicated concepts’ (unausgewickelte Begriffe)” (148). Finally: “To begin with, ‘the sublime’, like ‘the numinous’, is in Kantian language an idea or concept ‘that cannot be unfolded’ or explicated (unauswickelbar). Certainly we can tabulate some general ‘rational’ signs that uniformly recur as soon as we call an object sublime…But these are obviously only conditions of, not the essence of, the impression of sublimity. A thing does not become sublime merely by being great. The concept itself remains unexplicated; it has something mysterious, and in this it is like the numinous” (41).

So if we widen our understanding of knowledge then we might see a way forward to accept the feelings and unfolded concepts involved in aesthetic experience as knowledge of some kind. Moreover, we might try and find other arguments to support certain key ideas involved in his account. As already mentioned above, we can offer arguments in support of dualism to bolster the fundamental distinction between the sensible and the supersensible. And we might offer a defense of free will as well. In his essay On the Sublime Schiller offered the following argument for freedom based on the sublime:

“In presence of the sublime we feel ourselves sublime, because the sensuous instincts have no influence over the jurisdiction of reason, because it is then the pure spirit that acts in us as if it were not absolutely subject to any other laws than its own. The feeling of the sublime is a mixed feeling. It is at once a painful state, which in its paroxysm is manifested by a kind of shudder, and a joyous state, that may rise to rapture, and which, without being properly a pleasure, is greatly preferred to every kind of pleasure by delicate souls. This union of two contrary sensations in one and the same feeling proves in a peremptory manner our moral independence. For as it is absolutely impossible that the same object should be with us in two opposite relations, it follows that it is we ourselves who sustain two different relations with the object. It follows that these two opposed natures should be united in us, which, on the idea of this object, are brought into play in two perfectly opposite ways.”

And in his Foundations for the Metaphysics of Morals (see the third section entitled “Freedom Must be Presupposed as the Property of the Will of all Rational Beings”) Kant claims we are required to postulate free will in order to make sense of our moral agency and responsibility. After all, how can we be morally praised or blamed if we don’t assume we have the capacity to freely choose? If we find this line of reasoning sensible then we can build on it and offer the following rationally acceptable (not rationally compelling to be sure) argument for the existence of free will that is not explicitly connected to the sublime:

Premise 1: If we are morally responsible then we have free will: without free will the whole notion of choosing and being responsible for a choice would be nonsense. Indeed, ethics, which makes prescriptions or “oughts,” must assume people can choose.

Premise 2: We are indeed morally responsible as the practical aspects of our lives show: our personal relations, legal system, and political realities are infused with concepts and experiences of choice, regret, guilt, accountability, violations, responsibility, autonomy, punishment, and so on.

Conclusion: Therefore, we are free.

Those are just two ways we might supplement Kant’s account of the dynamic sublime (for more arguments for free will go to this helpful blog by William Vallicella). Let us now see if we can now further clarify and defend the idea of infinity in the mathematical sublime.

(8) We have seen that the mathematical sublime just is the idea of “infinity as a whole.” We have also seen that our grasping of this idea allows us to see how our reason has a “supersensible” aspect which transcends our finite human bodies in space and time. As Kant put it: “Sublime is what even to be able to think proves that the mind has a power surpassing any standard of sense.” And this certainly makes some sense: how could we think the infinite as a whole if we are just finite beings with finite minds that can only enact finite operations on completely finite material in finite time? But infinity is, to say the least, a perplexing and vast topic that has undergone significant changes in the 20th century (in the work of mathematician Georg Cantor for example). What exactly is infinity as a whole? We know it is not potential infinity. But can any positive account of it be given?

A.W. Moore, in his book The Infinite (Routledge, second edition, 2001), claims that Kant’s idea is a form of metaphysical infinity that is incoherent: “How can it be the case that what is infinite has to be understood on the model of what is finite [i.e., a bounded whole]? Must we conclude that the metaphysically infinite is, after all, incoherent, and that there is no way of describing the whole as a whole? Yes, I think we must – assuming that the metaphysically infinite really cannot be understood in any other way. The idea of the limited whole is incoherent” (193).

We have seen that Kant didn’t think we could represent the idea of infinity as a whole in our imagination. He also didn’t think we could empirically demonstrate it. But he did think we could theoretically project it as the result of a transcendental argument: the possession of the idea is the condition for the possibility of having our imagination defeated. He also claimed we can feel the presence of it through aesthetic experience. And he thought we could think it in a supersensible manner. Paul Crowther, in his book The Kantian Sublime: From Morality to Art (Oxford, 1989), elaborates:

“We can coherently think the idea of ‘given infinity’ if we regard the phenomenal world as limited or conditioned by the supersensible realm…The idea of ‘infinity as a whole’ or comprehended as a totality is coherent if we regard the supersensible substrate as serving, as it were, to circumscribe the world. Hence our very capacity coherently to think the idea of infinity as a whole is not only a manifestation of our rational supersensible being, but also entails reference to the supersensible as part of the content of the idea itself. This means that imagination’s inadequacy in an attempt to find an absolute measure both manifests the superiority of the supersensible and serves to draw our attention to the idea of it” (99).

And here we might incorporate a theistic line of thinking initiated by Rene Descartes who, in his Meditations on First Philosophy (Meditation Three), argued that our idea of an infinite being could only be caused by a truly infinite being that sustains our existence from moment to moment: “For although the idea of substance is within me owing to the fact that I am substance, nevertheless I should not have the idea of an infinite substance—since I am finite—if it had not proceeded from some substance which was veritably infinite.” This is his so-called “trademark argument” (see here for an overview).

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) by Frans Hals

These approaches might help a bit but they certainly leave us with a lot of questions and difficulties. In light of this, we might consider the possibility that the infinite is not even necessary for an adequate account of the mathematical sublime. In How Pictures Complete Us: The Beautiful, the Sublime, and the Divine (Stanford, 2016) Crowther writes: “Kant’s strained attempts to assign a role to infinity, here, is one of the major reasons why his account of the sublime is so difficult. Ironically enough, there is no philosophical necessity to invoke it at all. The very fact that we are led to search out an absolute measure for the vast phenomenon, logically entails that its vastness has already been found overwhelming. Some perceptual cue has engaged our rational interest in comprehending its totality – and challenged our imagination, but it is blatantly obvious in merely apprehending the object that its parts are not going to be comprehended adequately in a single image. The process that Kant describes in the above passage, in other words, is sufficiently accounted for as an immediate outcome of our attempt to apprehend vast phenomena as such. Imagination is overwhelmed without us ever having to bring in infinity as an aesthetic estimate. This being said, there are some occasions when the infinite may indeed play a role” (61). This interpretation of Kant is plausible although there are some, like Henry Allison, Patricia Matthews, and Simon Smith, who claim the notion of the infinite is necessary to Kant’s account. For a helpful overview of the controversy that shows the difficulties involved in both positions, go to this paper by Sacha Golob.

(9) Terry Eagleton, in his The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Blackwell, 1990), claims that the aesthetic category of the sublime is an ideology: “Both of these operations, the beautiful and the sublime, are in fact essential dimensions of ideology. For one problem of all humanist ideology is how its centring and consoling of the subject is to be made compatible with certain essential reverence and submissiveness on the subject’s part….The sublime in one of its aspects is exactly this chastening, humiliating power, which decentres the subject into an awesome awareness of its finitude, its own petty position in the universe, just as the experience of beauty shore it up” (90). But this doesn’t seem to apply to the Kantian sublime which, as we have seen, exalts us as moral beings and, despite the defeat the imagination experiences, allows the imagination to be expanded to its absolute limit in a way that is exhilarating. And we saw that, when Kant connects the sublime to religion, he stresses how one who realizes one’s dignity through the dynamic sublime will find a form of reverence that is not superstitious, submissive, or humiliating.

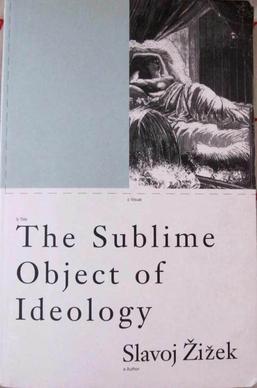

In his book The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989) Slavoj Žižek connects the Kantian sublime to ideology in a slightly different way. He claims various ideologies have central words, like God, Führer, King, and so on, which facilitate an irrational loyalty similar to the sublime. Consider this passage from the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Žižek: “Just as in the experience of the sublime, Kant’s subject resignifies its failure to grasp the sublime object as indirect testimony to a wholly “supersensible” faculty within herself (Reason), so Žižek argues that the inability of subjects to explain the nature of what they believe in politically does not indicate any disloyalty or abnormality. What political ideologies do, precisely, is provide subjects with a way of seeing the world according to which such an inability can appear as testimony to how Transcendent or Great their Nation, God, Freedom, and so forth is—surely far above the ordinary or profane things of the world.” This can lead such fanatical subjects to “transgress ordinary moral laws and lay down their lives.”

But this, too, can’t be right when applied to Kant. We have seen that the Kantian sublime is supposed to, among other things, make subjects aware of their capacity for rational moral duty. Moreover, the Kantian sublime can help prevent fanaticism. In his discussion of the sublime Kant claims fanaticism is the “delusion that we can will ourselves to see something beyond all bounds of sensibility.” But, as we have seen, “the inscrutableness of the Idea of Freedom quite cuts it off from any positive presentation” and “does not permit us to cast a glance at any ground of determination external to itself.” So the Kantian sublime can help us resist fanatics who think freedom and infinity can be possessed, objectified, represented, etc. in the form of a deceptive idol. Daniel Herwitz puts the point nicely in his book Aesthetics (Continuum, 2008):

“The sublime is that which resists incarnation in an individual, a nation, a group. Because it is an experience of an idea that has no presentation, no instance in the real world. It is meant to cause humility. When concretized as the aura of nation, of group, of individual, it causes the opposite, mass identification” (74).

And once we see that transcendence cannot be imaged we can resist the images used to conceal our transcendence. Kant observes that “governments have willingly allowed religion to be abundantly provided with the latter accessories [“images and childish ritual”]; and seeking thereby to relieve their subjects of trouble, they have also sought to deprive them of the faculty of extending their spiritual powers beyond the limits that are arbitrarily assigned to them, and by means of which they can be the more easily treated as mere passive beings.” But the sublime encourages us to be actively moral and to preserve our transcendent dignity in a media-saturated world of fanatics who seem to have forgotten that “there is no sublimer passage in the Jewish Law than the command, Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of anything which is in heaven or on the earth or under the earth, etc.” Thus I would argue Kant’s theory can help us resist ideologies of many kinds.

That said, we might still ask if there is the potential for ideology lurking somewhere. My suggestion is that it can lurk within his account of freedom itself. For if we think people are freer than they are then we might overlook various ways to truly liberate them which, in turn, can keep them in bondage. For example, I have epilepsy and I went undiagnosed for two years because everyone thought my complex partial seizures were acts of free will over which I had control. I was unable to get the medication that would restore my limited domain of freedom because people saw me as freer than I was. Something similar can happen on a political level when champions of liberty all too often deny help to people who suffer through no fault of their own. After all, if one thinks everyone is so radically free then one might think those who suffer must be the cause of their misery. Indeed, one might think they deserve to suffer the consequences of their so-called “free choices.” So a belief which overemphasizes freedom can be ideological insofar as it distorts our understanding of humanity and helps undermine the very freedom it champions.

(10) We have seen that the aesthetic judgments of the Kantian sublime are about individual feelings in response to the supersensible ideas of infinity and independence. Does this emphasis on feeling and supersensibility cut us off too much from each other and the realms of morality, politics, and culture? James Elkins, in his provocative article “Against the Sublime” which appears in the book Beyond the Finite: The Sublime in Art and Science (Oxford, 2011), claims that the sublime “has nothing to say about the things that count in visual culture – especially gender, identity, and politics.” It also “takes people away from the real world of politics and society, of meaning and narrative, and culture and value” insofar as it “can only sing a plaintive song about longing.” And he approvingly cites Richard Rorty’s assessment that the sublime is “one of the prettier unforced blue flowers of bourgeois culture” that is “wildly irrelevant to the attempt at communicative consensus” so important to culture. This irrelevance follows from the fact that the sublime is essentially a religious discourse “beyond the reach of critical thought” (87). Does this line of critique apply to Kant?

Well, Kant does say that “separation from all society is regarded as sublime” if, rather than being “unsociable,” it fosters “self-sufficiency” and a “dispensing with wants” that marks moral duty. Perhaps Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Monk by the Sea (1810) expresses this kind of sublime solitude:

But I think the foregoing can help us see that Kant’s account of the sublime, far from being some historical curiosity irrelevant to us today, is capable of contributing to contemporary culture in various ways.

First, the sublime reveals something fundamental to social, political, and cultural issues of value, namely, our moral agency. After all, we need to be autonomous moral agents who can value the world if we are to address various issues of value.

Second, the human dignity revealed in the sublime is often inseparable from such issues which are often a function of people not being treated with dignity. Thus the sublime can provide aesthetic grounds for taking this dignity seriously and extending it to others. I explored this extension of the sublime in my discussion of Kant’s notion of a sublime culture. Moreover, the sublime holds out the promise that the hostile forces of the world can never take away this dignity.

Third, we have just seen that Kant’s account is incredibly relevant to “visual culture” in that it helps us understand that there is more to human freedom and dignity than images. This can help us guard against ideologies, fanaticism, and various forms of idolatry in our image-saturated culture.

And fourth, the unpresentable aspects of the sublime need not exclude it from “communicative consensus.” Kant claims the sublime is “distinguishable from other aesthetical judgements by its universal communicability, but also because, through this very property, it acquires an interest in reference to society (in which this communication is possible).” Here we can recall Kant’s criteria of universality which requires us to make a gesture towards consensus guided by the belief that others should agree with us. This gesture can be accomplished by pointing people to the conditions under which we had an experience. I can tell others to look at something intersubjectively available – say a majestic landscape, the starry heavens, or artwork that imitates these things – so that they can make their own reflective judgments that seek and eventually find both infinity and independence as well. I certainly think anyone who witnessed what I witnessed from that plane and ship would experience what I experienced. And the necessity for such a projected consensus is grounded in our shared rational and imaginative nature which cuts across nationality, class, race, gender, party affiliation, and so on.

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon (ca. 1825-30)

If people can experience phenomena boundless in might or magnitude in a disinterested way then they can, despite their diverse experiences, beliefs, and cultures, have their shared mental faculties activated in the same way. And these shared experiences can provide a common ground for aesthetic critique. The fact that we cannot imagine or scientifically demonstrate the sublime may be a limitation some find difficult to accept. But Kant’s appeal to our shared nature offers a way to avoid a complete subjectivism of feeling and is certainly not a religious discourse “beyond the reach of critical thought.”