213. Sublime Minimalism

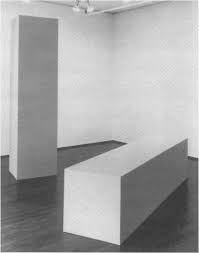

Donald Judd, Untitled (1980-84)

The art movement known as minimalism is not easy to define and, when applied to artists, their works, and their audiences, usually ends up oversimplifying things. Nonetheless, there is a set of family resemblances that can help us put the word to good use. James Meyer, in his book Minimalism (Phaidon, 2000), provides a helpful account of such resemblances:

“Although never exactly defined, the term ‘Minimalism’ (or ‘minimal art’) denotes an avant-garde style that emerged in New York and Los Angeles during the 1960s, most often associated with the work of Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt and Robert Morris, and other artists briefly associated with the tendency. Primarily sculpture, Minimal art tends to consist of single or repeated geometric forms. Industrially produced or built by skilled workers following the artist’s instructions, it removes any trace of emotion or intuitive decision-making, in stark contrast to the Abstract Expressionist painting and sculpture that preceded it during the 1940s and 1950s. Minimal work does not allude to anything beyond its literal presence, or its existence in the physical world. Materials appear as materials; colour (if used at all) is non-referential. Often placed on walls, in corners, or directly on the floor, it is an installation art that reveals the gallery as an actual place, rendering the viewer conscious of moving through this space” (15).

It is important to note that some artists associated with the minimalist movement, such as Agnes Martin and Anne Truitt, tried to use minimal techniques to convey transcendent, spiritual, and sublime meanings (see my post on Agnes Martin here). But most minimalist works will not be a function of (1) any imitation or representation of other things or events; (2) any transcendent experience or metaphysical vision; and (3) any intellectual experience that might come from metaphor, allegory, symbolism, and so on. For example, Frank Stella, commenting on his painting The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II, asserted, “What you see is what you see.”

Frank Stella, The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II (1959)

At the MoMA site we get this helpful description: “Frank Stella used commercial black enamel paint and a house painter’s brush to make The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II. The thick black bands are the same width as the paintbrush he used. The thin white lines are not painted; they are gaps between the black bands in which the raw canvas is visible. Stella painted the black bands parallel to each other, and to the canvas’s edges, rejecting expressive brushstrokes in favor of an overall structure that recognized the canvas as both a flat surface and a three-dimensional object. Stella identified his materials and process with those of a factory laborer. About his manner of painting, Stella famously said, “My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there… What you see is what you see.” Instead of painting something recognizable, Stella’s painting is about the act of painting, and its result.”

In contrast to expressionists and abstract expressionists, who tried to convey emotions and/or ideas, Stella’s black paintings from the late fifties and early sixties employed serial methods of composition in order to remove traces of the world beyond the paint and canvas. They were designed not to refer to, imitate, or represent anything. They simply are what they are and the viewer is invited to experience them as such.

Robert Morris’ work Two Columns (1961) provides another example of this aesthetic agenda. Morris said his work was an “essentially empty” sculpture with “nothing to say”:

Many experience the 120 fire bricks that comprise Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966) as empty and mute as well:

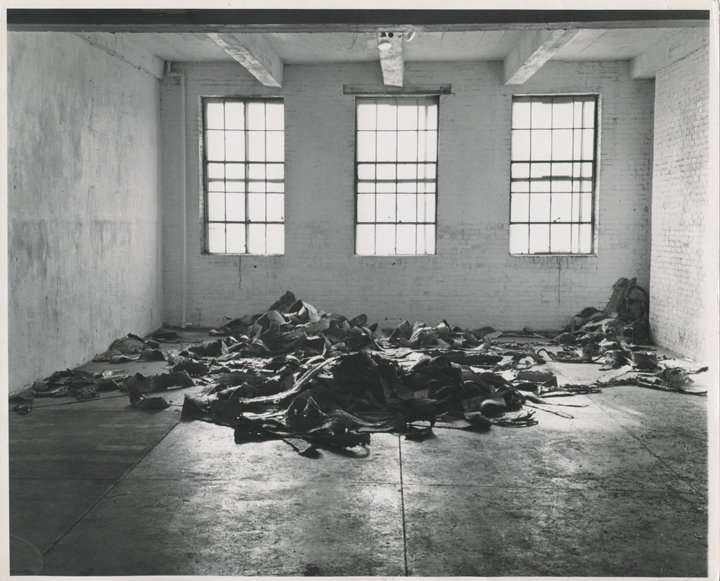

Ditto for Richard Serra’s Scatter Piece (1967) comprised of rubber:

However, these works can draw our attention to the materials out of which they are made for their own sake. How often do we really look at rubber, bricks, columns, and paint as such? All too often we are interested in what things represent rather than things themselves. And when we look at so-called ordinary things like bricks we may come to be amazed by the nuances that are revealed. This capacity of certain minimalist works to illuminate the ordinary shouldn’t be overlooked. It can reveal that many seemingly meaningless minimalist works really have meaning after all: not instrumental meaning, where the materials are a means to representational ends outside themselves, but rather the inherent meaning of the materials themselves and their own expressive properties.

But, let’s face it, staring at rubber, bricks, columns, and silver paint might leave us without that sense of dramatic intensity and power we often long for in art. This disappointment, however, may be unnecessary since, paradoxically, the lack of transcendent meaning so prominent in many minimalist works can be the occasion for transcendent meaning. How might this be the case?

Well, consider that there can be an uncanny sensation when we confront art that doesn’t speak to us by way of external reference. Our expectations are thwarted by mute objects with their meaningless repetitions and lack of subjectivity. In such a confrontation we may have an aesthetic experience of death insofar as the development, meaning, and communication so integral to life is eerily suspended. Such an experience wouldn’t be surprising given the inorganic aspect of geometric shapes. As Donald Judd noted: “The main virtue of geometric shapes is that they aren’t organic, as all art otherwise is.” And Michael Leyton, in his work Symmetry, Causality, Mind (MIT Press), argues that symmetry is really a form of indistinguishability that “prevents the inference of history”, that is, it prevents us from extracting any information about where something came from (586). This indistinguishability can invoke a sense of temporal suspension: “According to our analysis, symmetry is the destruction of time. It is the absence of process, development, growth, action. In contrast, asymmetry means change—it means interaction, progressive organization, unfolding.” This connection between symmetry and timelessness allows Leyton to go on and assert that “life requires asymmetry” and that “death is, technically, an example of symmetry” (35).

Donald Judd, Untitled (1967)

Now, this aesthetic confrontation with death certainly sounds like the opposite of a transcendent experience! But we might see things differently if we invoke something which Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), in his book Critique of Judgment (1790), referred to as the dynamic sublime. Typically this form of the sublime occurs when we make judgments about mighty things that have the capacity to destroy our physical well-being. Kant offers some examples: “Bold, overhanging, and, as it were, threatening rocks, thunderclouds piled up the vault of heaven, borne along with flashes and peals, volcanoes in all their violence of destruction, hurricanes leaving desolation in their track, the boundless ocean rising with rebellious force, the high waterfall of some mighty river, and the like, make our power of resistance of trifling moment in comparison with their might.”

John Martin, The Great Day of His Wrath (circa 1851)

In such cases we experience the might of nature and, to be sure, experience displeasure in the revelation that our physical powers, even when extended by technology, are so exceedingly small. But if we are making a judgment of the sublime we also imagine that we are free to stand up to such overpowering might if we so choose. This imaginative resistance reveals that, while our body and personal belongings are obviously dependent on the forces of nature, our personhood exists as free and independent of these forces. This awareness of our transcendent freedom allows pleasure to follow displeasure. Thus the sublime is able to edify us as free souls even as it shows us the limits of our bodies. This is important since for Kant our capacity to act freely is what makes morality possible (for my thorough account of the sublime in Kant’s philosophy go here).

Now, we have seen that minimalist works may be interpreted as having a lack of drama, intensity, power, and so on. They certainly don’t confront us with images like John Martin’s sublime painting above. But if we include the silent experiences of minimalist death as a means to invoking fear, then I think we can see how, when confronted with such aesthetic analogues of annihilation, we might have an occasion to experience the sublime and thus our transcendental freedom. And this experience, far from being undramatic, could be quite transformative indeed. Perhaps, then, minimalist works can be the means to the very transcendence many think they exclude.

Anne Truitt, Southern Elegy (1962)

For more of my posts on aesthetics, go here.