222. Plato on virtue and its connection to soul, beauty, and love

Plato (detail from Raphael’s The School of Athens)

When we engage in the philosophical activity of ethics we ask questions like: what are right and wrong actions? What does it mean for something to be good or bad? What is just and unjust? What is virtuous and vicious? What is evil? Typically, philosophers offer normative theories which define our general and fundamental moral terms and offer principles with which to make moral judgments. For example, utilitarianism is a moral theory that defines good as pleasure and bad as pain. It then offers a principle, the greatest happiness principle, which states an action is right if it generates pleasure for the majority of those involved in the situation. One can then follow this principle in order to discern the right course of action in a morally problematic situation. And one can, in turn, use the principle to justify one’s actions. Of course, many other theories have been offered (Kantian ethics, virtue ethics, natural law theory, ethical egoism, ethics of care, etc.) and contemporary students of ethics typically work through these theories and then see how they apply to a wide variety of moral issues such as euthanasia, abortion, capital punishment, the death penalty, cloning, war, and so on.

The activity of ethics has continued to be an important and popular aspect of philosophy since at least ancient Greece. In looking at the history of the subject, one can find continuities over the centuries in terms of the questions asked and the answers explored. But there are discontinuities as well. In this post I want to explore what I take to be a few of these discontinuities, namely, that ancient, medieval, and even enlightenment-era ethics had implicit or explicit connections to soul, love, and beauty. Most people who study philosophical ethics today never come across these topics. This would perplex many earlier philosophers. Perhaps, above all, it would perplex Plato (427-347 BC). Therefore, in this post I will give a brief overview of Plato’s views on the soul, love, and beauty in order to show how closely they are connected to the development of virtue. These views and connections can certainly be controversial and may even seem outlandish to some. But I think they are as interesting as they are inspiring and deserve far more attention than they typically receive. Let’s begin with Plato’s vision of the soul.

Plato on the Soul

Plato wrote dialogues that feature Socrates talking with various characters about various topics. The topic of the soul appears in many of his works and various insights into its nature are offered. If we take these insights into account, then I think we can piece together the following tentative definition: the soul is a self-moving, immaterial substance with three fundamental desires. These desires are metaphorically and dynamically described in his dialogue Phaedrus as a charioteer with a team of two horses. The charioteer represents reason, the obedient white horse represents spirit, and the disobedient dark horse represents appetite. Our appetite comprises those desires related to physical pleasure and well-being: food, drink, and sex. It also represents a desire for the material conditions to acquire these things such as money. Our spirit comprises those desires for social well-being: honor, fame, power, recognition, etc. And reason comprises those desires we have for intellectual well-being: truth, knowledge, and understanding. These are not physical parts of the soul since the soul is not physical. Rather, they are different functions or powers of the soul that can be distinguished upon analysis. We should also note that Plato writes various passages suggesting that appetite and spirit, unlike reason, exist due to our embodied state which brings with it concerns for physical pleasure and social esteem.

Plato articulates a set of virtues that correspond to these aspects of the soul. If the soul is predominantly directed by reason then the soul exhibits wisdom. The charioteer will be able to intelligently guide the obedient white horse, the horse that desires honor, to run after the appropriate objects of social esteem. If such intelligent guidance of the desire for honor is present then the spirited function will manifest the virtue of courage. And with the help of the white horse, the charioteer can moderate the unruly appetites. If this is the case then appetite will manifest the virtue of moderation. When the rational part of the soul moderates appetite with the help of spirit then we have the virtue of the whole soul, namely, justice. Like a well-regulated state, each aspect of the soul will know its place and will contribute to the well-being of the whole person.

Just the opposite occurs if the dark horse or appetite runs the soul. For without the guidance the dark horse runs after everything it wants and the white horse, the sense of honor and shame, can’t do much to stop it. And the charioteer’s reason can’t intelligently direct the appetites since the dark horse doesn’t listen to reason. At best, the charioteer is reduced to calculating the means to the next physical pleasure. So what we end up with is an unjust soul that is immoderate since the appetites have free reign; cowardly because spirit can’t veto the viciousness and induce effective shame; and profoundly ignorant since intelligence doesn’t direct the soul’s actions. Naturally, this unjust soul configuration can have serious consequences. In relationships, it can lead to an immoral form of love in which people are only interested in satiating their selfish needs and pursue these needs with little or no shame. In politics it can lead to injustice, unjust war, and tyranny. But perhaps the greatest toll is on the unjust soul itself which fails to rationally direct itself and actualize its nature as self-moving. Rather than becoming a being which can originate actions for which it can be morally responsible, it becomes more akin to an addict lacking autonomy and shame due to its immoderation.

This analysis of virtue has resonances with modern day virtue ethics which also offer prescriptions to develop a character that is wise, courageous, moderate, and just. But Plato’s inclusion of the soul is not something you will find too often. Moreover, his prescription for developing a self-moving and virtuous soul includes both the experience of beauty and love. So let’s take a look at how both these factors play a role.

Beauty and its Role in Forming a Just Soul

In his dialogue Symposium, Plato has his character Socrates describe an eternal and perfect form of beauty which he says he heard from a priestess by the name of Diotima:

“He who has been instructed thus far in the things of love, and who has learned to see the beautiful in due order and succession, when he comes toward the end will suddenly perceive a nature of wondrous beauty (and this, Socrates, is the final cause of all our former toils) – a nature which in the first place is everlasting, not growing and decaying, or waxing and waning; secondly, not fair in one point of view and foul in another, or at one time or in one relation or at one place fair, at another time or in another relation or at another place foul, as if fair to some and foul to others, or in the likeness of a face or hands or any other part of the bodily frame, or in any form of speech or knowledge, or existing in any other being, as for example, in an animal, or in heaven or in earth, or in any other place; but beauty absolute, separate, simple, and everlasting, which without diminution and without increase, or any change, is imparted to the ever-growing and perishing beauties of all other things.”

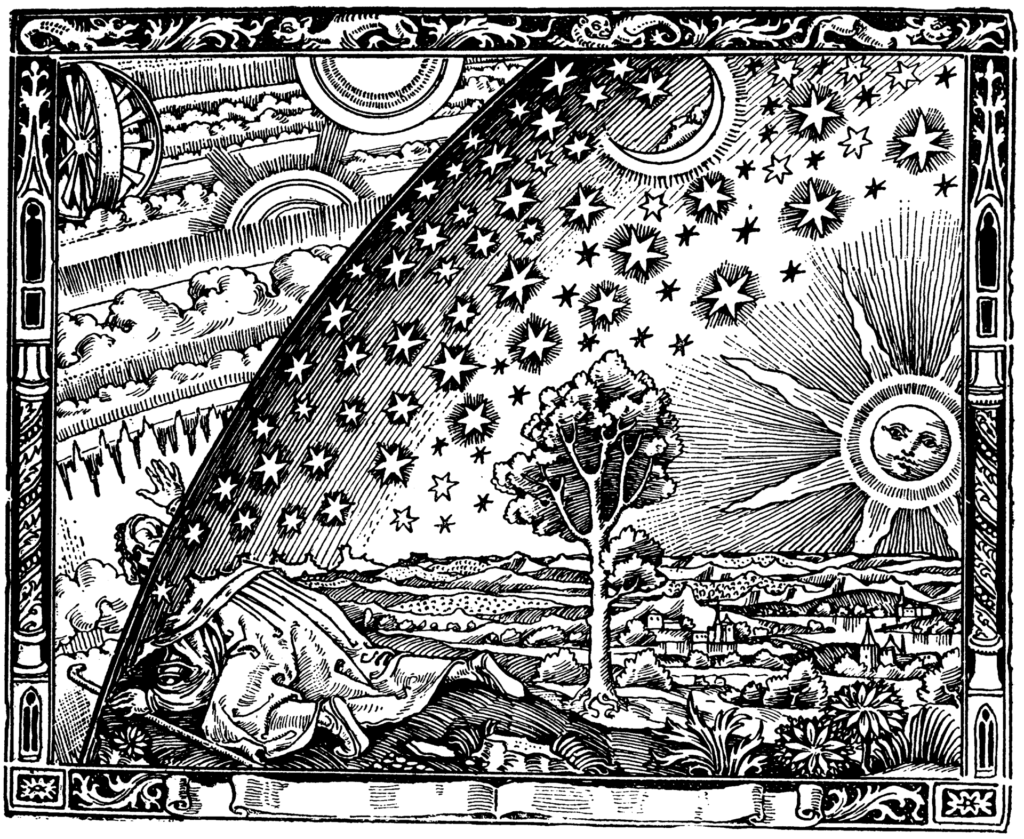

So the imperfect and changing beautiful things of our physical world participate in the perfect and unchanging Form of the Beautiful Itself. In his dialogue Phaedrus, Plato points out that our encounter with sensible beauty allows the rational part of our soul to come into contact with this Form as well as the Form of Moderation to which it is closely related. In sensing these transcendental realities we are reminded of our kinship to the divine. Consider these remarkable passages from Phaedrus in which Plato explores the transformative dimension of this encounter:

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486) Venus calls us to unite with her through the soul in a way that transcends the carnal appetites!

“As I said at the beginning of this tale, I divided each soul into three-two horses and a charioteer; and one of the horses was good and the other bad: the division may remain, but I have not yet explained in what the goodness or badness of either consists, and to that I will proceed. The right-hand horse is upright and cleanly made; he has a lofty neck and an aquiline nose; his colour is white, and his eyes dark; he is a lover of honour and modesty and temperance, and the follower of true glory; he needs no touch of the whip, but is guided by word and admonition only. The other is a crooked lumbering animal, put together anyhow; he has a short thick neck; he is flat-faced and of a dark colour, with grey eyes and blood-red complexion; the mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf, hardly yielding to whip and spur. Now when the charioteer beholds the vision of love, and has his whole soul warmed through sense, and is full of the prickings and ticklings of desire, the obedient steed, then as always under the government of shame, refrains from leaping on the beloved; but the other, heedless of the pricks and of the blows of the whip, plunges and runs away, giving all manner of trouble to his companion and the charioteer, whom he forces to approach the beloved and to remember the joys of sex. They at first indignantly oppose him and will not be urged on to do terrible and unlawful deeds; but at last, when he persists in plaguing them, they yield and agree to do as he bids them. And now they are at the spot and behold the flashing beauty of the beloved; which when the charioteer sees, his memory is carried to the true beauty, whom he beholds in company with Modesty like an image placed upon a holy pedestal. He sees her, but he is afraid and falls backwards in adoration, and by his fall is compelled to pull back the reins with such violence as to bring both the steeds on their haunches, the one willing and unresisting, the unruly one very unwilling; and when they have gone back a little, the one is overcome with shame and wonder, and his whole soul is bathed in perspiration; the other, when the pain is over which the bridle and the fall had given him, having with difficulty taken breath, is full of wrath and reproaches, which he heaps upon the charioteer and his fellow steed, for want of courage and manhood, declaring that they have been false to their agreement and guilty of desertion. Again they refuse, and again he urges them on, and will scarce yield to their prayer that he would wait until another time. When the appointed hour comes, they make as if they had forgotten, and he reminds them, fighting and neighing and dragging them on, until at length he, on the same thoughts intent, forces them to draw near again. And when they are near he stoops his head and puts up his tail, and takes the bit in his teeth. and pulls shamelessly. Then the charioteer is worse off than ever; he falls back like a racer at the barrier, and with a still more violent wrench drags the bit out of the teeth of the wild steed and covers his abusive tongue and jaws with blood, and forces his legs and haunches to the ground and punishes him sorely. And when this has happened several times and the villain has ceased from his wanton way, he is tamed and humbled, and follows the will of the charioteer, and when he sees the beautiful one he is ready to die of fear. And from that time forward the soul of the lover follows the beloved in modesty and holy fear.”

Here we have an astonishing account of how the unruly, shameless, arational, and profoundly dangerous appetites come to be moderated with the help of the experience of beauty. In seeing the beauty of the beloved’s face, reason is reminded of its kinship to divine beauty and, being so reminded, it enters a state of contemplation which arrests appetite. In this state we also feel shame for having been pulled around by our appetites. As a result, our soul’s rational faculty can gain the control it needs to pursue virtue. The Form of Beauty is thus a supernatural aid – indeed the only one that appears to our physical senses according to Plato – which helps us avoid a vicious and completely earthbound life.

Cupid and Psyche, Francois-Edouard Picot (1817)

Eros and Character Types

In his dialogue Symposium, Plato has Socrates relate a narrative which describes love or Eros as an in-between spirit – a spirit that exists in-between mortals and immortals – that can inflame our desires and purposefully move them towards various objects. But different people channel this erotic energy differently. How they channel Eros contributes to who they are as people. If Eros gives a soul a love of wisdom (philosophy) then the soul will be dominated by the charioteer or reason. If Eros gives the soul a love of honor then the soul will be dominated by the white horse or spirit. If Eros gives the soul a love of bodily pleasure then the soul will be dominated by the black horse or appetite. Based on this account, we can see that we have three types of people: those who primarily love truth; those that primarily love honor; and those that primarily love physical pleasure.

Now a lover of honor is certainly better than a lover of appetite. This person will take shame seriously and be involved in social relations that afford praise, blame, sacrifice, and so on. But here, too, we have a danger. If one’s love of honor is not directed by reason then one is bound to pursue the wrong objects of esteem. One can think of so many people who do immoral things for their love of recognition. Their charioteers lose control and the white horse runs the show without much direction. So we will need to be lovers of wisdom if we are going to develop a just soul. And this means divine Eros must assist our souls in their efforts to transcend the immediate concerns of the world and seek truth which reason, the charioteer, needs as “nourishment.” Understanding this, we can think about the different ways education, in all its forms, can facilitate the love of wisdom – philosophy – in order to produce just souls that are fulfilled individually and collectively (see book 7 of Plato’s Republic for some insights about how philosophical education will require the trivium – grammar, rhetoric, and logic – as well as the quadrivium – geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music).

Is Modern Moral Theory Impoverished?

So we see that, according to Plato, the cultivation of virtue is inseparable from an understanding of the soul and how both beauty and love affect it. Most modern moral theory, whether it be metaethics, normative ethics, or applied ethics, has nothing to say about these topics. To be sure, there are many who think modern moral philosophy is far superior as a result. But it strikes me that the theory, distinctions, arguments, terminology, and so on that we now have at our disposal is, despite its sophistication and power, a bit impoverished and could greatly benefit from taking Plato’s insights more seriously. Naturally, we need not simply accept Plato’s account of soul, beauty, and love. We might think of love as, for example, agape rather than Eros. We might take Plato’s descriptions of the psyche’s dynamics seriously but try and ground them in brain functions or what naturally emerges from such functions. Or we might seek an evolutionary account of beauty that can dispense with Plato’s metaphysics. But the topics themselves seem profoundly relevant and exploring new ways in which they can be understood and integrated into our moral lives seems like a project well worth pursuing.

For my post which argues there cannot be a comprehensive science of Eros, go here.

For my many posts on beauty, go here.

For a series of posts that explore one of Plato’s arguments for the immortality of the soul, go here.

For Plato’s argument that the soul is an immaterial unity not reducible to the brain, go here.

Hi Dwight

Thanks for this website!

I’m teaching a subject called Law in context

Somebody else designed it and sometimes I feel it lacks certain dimensions

Do you have any Commentary written by yourself or that you recommend on beauty and its role in a liberal democracy? Or any thoughts you might Permit me to share with my students On that?

Thanks Dwight!