252. Some Notes on Freud’s Death Instinct

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) offered the world plenty of fascinating and often shocking ideas. His seduction theory, infantile sexuality, parapraxes (Freudian slips), Oedipus complex, Electra complex, penis envy, castration anxiety, forms of fixation, and vision of an unconscious mind full of repressed content that nonetheless affects our conscious life are as influential as they are controversial. But one of his ideas, one to which he was profoundly committed, was that humans have a death instinct. This idea was not well-received even in Freud’s day and has since found few champions. I am sympathetic to it although I will not be defending it in this post. Rather, I offer some notes about it to facilitate some basic understanding. My opinion is that Freud’s most powerful intuitions, while certainly not beyond criticism, are worthy of our serious attention and what follows is an aid for developing such attention.

In chapter 6 of his Civilizations and its Discontents (1930) Freud recalls his earlier work and how he made a central distinction between ego-instincts, which are directed at self-preservation, and libidinal-instincts which strive towards external objects and are often at odds with the self: “Thus the antithesis was between the ego-instincts and the ‘libidinal’ instincts of love (in its widest sense) which were directed to an object.” This antithesis allowed Freud to explain neurosis: “Neurosis was regarded as the outcome of a struggle between the interest of self-preservation and the demands of the libido, a struggle in which the ego had been victorious but at the price of severe sufferings and renunciations.” Freud continues and notes that he came to see things weren’t quite so simple when he explored narcissism and discovered “that the ego, indeed, is the libido’s original home, and remains to some extent its headquarters. This narcissistic libido turns towards objects, and thus becomes object-libido; and it can change back into narcissistic libido once more.” So ego-instincts turned out to be libidinal as well.

But things became even more complicated when he realized there was more than one basic instinct: “My next step was taken in Beyond the Pleasure Principle [1920] when the compulsion to repeat and the conservative character of instinctual life first attracted my attention. Starting from speculations on the beginning of life and from biological parallels, I drew the conclusion that, besides the instinct to preserve living substance and to join it into ever larger units, there must exist another, contrary instinct seeking to dissolve those units and to bring them back to their primaeval, inorganic state. That is to say, as well as Eros there was an instinct of death. The phenomena of life could be explained from the concurrent or mutually opposing action of these two instincts.” Here is the passage from Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Norton and Company, 1961):

“Every modification which is thus imposed upon the course of the organism’s life is accepted by the conservative organic instincts and stored up for further repetition. Those instincts are therefore bound to give a deceptive appearance of being forces tending towards change and progress, whilst in fact they are merely seeking to reach an ancient goal by paths alike old and new. Moreover it is possible to specify this final goal of all organic striving. It would be in contradiction to the conservative nature of the instincts if the goal of life were a state of things which had never yet been attained. On the contrary, it must be an old state of things, an initial state from which the living entity has at one time or other departed and to which it is striving to return by the circuitous paths along which its development leads. If we were to take it as a truth that knows no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons—becomes inorganic once again—then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones’” (32).

Freud notes that in Goethe’s Faust Mephistopheles offers an “exceptionally convincing identification of the principle of evil with the destructive instinct” and quotes a few lines:

For all things, from the Void

Called forth, deserve to be destroyed…

Thus, all which you as Sin have rated—

Destruction,—aught with Evil blent,—

That is my proper element.

He also notes that “The Devil himself names as his adversary, not what is holy and good, but Nature’s power to create, to multiply life—that is, Eros” and quotes these lines:

From Water, Earth, and Air unfolding,

A thousand germs break forth and grow,

In dry, and wet, and warm, and chilly:

And had I not the Flame reserved, why, really

There’s nothing special of my own to show.

(all lines from Part I, Scene 3; translated by Bayard Taylor)

Faust and Mephistopheles by Eugène Siberdt (ca. 1900)

Thus Freud finally accepts this conceptual distinction as fundamental: “The name ‘libido’ can once more be used to denote the manifestations of the power of Eros in order to distinguish them from the energy of the death instinct.”

Freud observes that many people resist the idea of the death drive. They are like “little children who don’t like it” because they think they are made in God’s image and exempt from an inherent drive that causes so much evil. And others, even fellow psychoanalysts, find it far too speculative to be taken seriously as a scientific hypothesis. Freud admits that he, too, initially had doubts about the drive but now he can “no longer think in any other way.” True, Eros is far easier to detect than the death drive. But he claims the latter can be detected when sadism and narcissism appear alongside Eros: “It must be confessed that we have much greater difficulty in grasping that instinct; we can only suspect it, as it were, as something in the background behind Eros, and it escapes detection unless its presence is betrayed by its being alloyed with Eros. It is in sadism, where the death instinct twists the erotic aim in its own sense and yet at the same time fully satisfies the erotic urge, that we succeed in obtaining the clearest insight into its nature and its relation to Eros. But even where it emerges without any sexual purpose, in the blindest fury of destructiveness, we cannot fail to recognize that the satisfaction of the instinct is accompanied by an extraordinarily high degree of narcissistic enjoyment, owing to its presenting the ego with a fulfilment of the latter’s old wishes for omnipotence. The instinct of destruction, moderated and tamed, and, as it were, inhibited in its aim, must, when it is directed towards objects, provide the ego with the satisfaction of its vital needs and with control over nature.” Moreover, he claims accepting the death drive allows us to simplify our world view and explain many otherwise inexplicable masochistic and sadistic phenomena not related to love under one heading. And it promises to bear fruit in many other inquiries: “The opposition which thus emerges between the ceaseless trend by Eros towards extension and the general conservative nature of the instincts is striking, and it may become the starting-point for the study of further problems.”

One problem which the death drive can help solve is the problem of Civilizations and its Discontents itself: the problem of civilization. Freud writes: “I was led to the idea that civilization was a special process which mankind undergoes, and I am still under the influence of that idea. I may now add that civilization is a process in the service of Eros, whose purpose is to combine single human individuals, and after that families, then races, peoples and nations, into one great unity, the unity of mankind. Why this has to happen, we do not know; the work of Eros is precisely this. These collections of men are to be libidinally bound to one another. Necessity alone, the advantages of work in common, will not hold them together. But man’s natural aggressive instinct, the hostility of each against all and of all against each, opposes this programme of civilization. This aggressive instinct is the derivative and the main representative of the death instinct which we have found alongside of Eros and which shares world-dominion with it. And now, I think, the meaning of the evolution of civilization is no longer obscure to us. It must present the struggle between Eros and Death, between the instinct of life and the instinct of destruction, as it works itself out in the human species. This struggle is what all life essentially consists of, and the evolution of civilization may therefore be simply described as the struggle for life of the human species. And it is this battle of the giants that our nurse-maids try to appease with their lullaby about Heaven.”

Death and Life (1910) by Gustav Klimt

One of the most enduring and startling insights from his investigation of civilization in these terms of Eros and death comes in chapter 4 with his account of sublimation which shows how our libidinal instincts, in becoming necessarily repressed by the norms and laws of civilization, come out indirectly in ways that end up generating many impressive aspects of that very civilization such as music, art, religion, and so on. These sublimations, according to Freud, are substitutions for what we really want, namely, satisfying genital love: “We said there that man’s discovery that sexual (genital) love afforded him the strongest experiences of satisfaction, and in fact provided him with the prototype of all happiness, must have suggested to him that he should continue to seek the satisfaction of happiness in his life along the path of sexual relations and that he should make genital erotism the central point of his life.” As a result we find them disappointing on some level. But they are nonetheless capable of giving us some degree of happiness in our compromised and civilized state—a state far safer than living without the protections, cleanliness, law, and cultural experiences it offers.

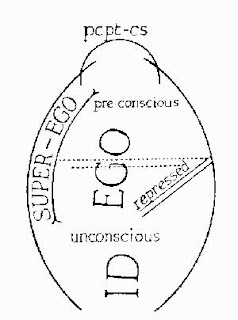

Freud’s diagram of the relationship of id, ego, and superego. The area labeled “pcpt-cs” (perceptual-conscious system) is the the interface with the external world.

Another enduring insight of his analysis of civilization in terms of Eros and death focuses on the latter and postulates that the conscience or super-ego is actually the death instinct turned toward the ego as a result of social prohibitions. What is interesting is that this aggression towards the self ends up, on one hand, serving Eros’ civilization-building dynamics by keeping people obedient in accordance with their own internal censors and, on the other hand, making them discontented since so many super-egos set up impossible standards that cause suffering. He explains: “Another question concerns us more nearly. What means does civilization employ in order to inhibit the aggressiveness which opposes it, to make it harmless, to get rid of it, perhaps? We have already become acquainted with a few of these methods, but not yet with the one that appears to be the most important. This we can study in the history of the development of the individual. What happens in him to render his desire for aggression innocuous? Something very remarkable, which we should never have guessed and which is nevertheless quite obvious. His aggressiveness is introjected, internalized; it is, in point of fact, sent back to where it came from—that is, it is directed towards his own ego. There it is taken over by a portion of the ego, which sets itself over against the rest of the ego as super-ego, and which now, in the form of ‘conscience’, is ready to put into action against the ego the same harsh aggressiveness that the ego would have liked to satisfy upon other, extraneous individuals. The tension between the harsh super-ego and the ego that is subjected to it, is called by us the sense of guilt; it expresses itself as a need for punishment. Civilization, therefore, obtains mastery over the individual’s dangerous desire for aggression by weakening and disarming it and by setting up an agency within him to watch over it, like a garrison in a conquered city.”

He concludes the book with a question written just a few years before WWII began: “The fateful question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction. It may be that in this respect precisely the present time deserves a special interest. Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man. They know this, and hence comes a large part of their current unrest, their unhappiness and their mood of anxiety. And now it is to be expected that the other of the two ‘Heavenly Powers’, eternal Eros, will make an effort to assert himself in the struggle with his equally immortal adversary. But who can foresee with what success and with what result?”

So according to Freud Eros and the death drive are the two closely connected fundamental forces of the universe and their interplay allows us to understand the dynamics of civilization and its discontents. Given their close connection it can be hard to decipher them. But one reason for trying is this: by understanding the machinations of the death drive we can reduce some of its power, make people less discontented, and aid Eros in its struggle with its immortal adversary Thanatos.

Further reading:

Freud’s Civilizations and its Discontents, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and “The Economic Problem of Masochism.” I also found the following books helpful in understanding and critiquing the death instinct: Terry Eagleton’s Holy Terror which explores the death drive in relation to forms of terrorism in history and contemporary society; Death and Delusion: A Freudian Analysis of Moral Terror by Jeffrey Piven which analyzes and applies death-related issues in Freud; Modern Man and Mortality by Jacques Choron (chapter 3) which offers an informative, sympathetic, and critical analysis; The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker (chapter 6) which offers a critical analysis; and Psychoanalytic Reflections on The Freudian Death Drive: In Theory, the Clinic, and Art by Rossella Valdrè which “investigates the relevance, complexity and originality of a hugely controversial Freudian concept which, the author argues, continues to exert enormous influence on modernity and plays an often-imperceptible role in the violence and so-called “sad passions” of contemporary society” (official Amazon description).

For my other posts on Freud, go here.

For my ongoing blog series on Eros and Thanatos, go here.