217. Fighting the Gravity of Vice: An Essay on Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth

Fighting the Gravity of Vice: An Essay on Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth

Dwight Goodyear

Introduction (Spoiler Alert)

The cult classic The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) is one of my favorite films. It was directed by Nicolas Roeg (1928-2018), written by Paul Mayersberg, and is based on the novel of the same name by Walter Tevis (1928-1984). It also presents David Bowie (1947-2016) in a justly celebrated debut role as an alien who comes to earth to obtain water for his drought-ridden planet. To accomplish this task, he uses his superior knowledge to secure a set of revolutionary patents and launch World Enterprises Corporation. This successful business venture makes him wealthy enough to fund a space program that will enable him to bring water to his planet. This intelligent, peaceful, telepathic, and trusting alien, who goes by the name of Thomas Jerome Newton, experiences plenty of wonderful things the earth in general, and America in particular, has to offer. But he also directly or indirectly encounters plenty of destructive influences as well. For the most part he is able to keep his good nature intact despite being affected by them. But, in the end, he can’t escape alcohol addiction and a government that insures the failure of his mission. He falls to earth both literally and metaphorically.

The film is odd in that it intentionally employs aspects of multiple genres such as sci-fi, horror, melodrama, erotica, psychedelia, satire, western, and mystery. It also unfolds with plenty of poetic associations, obscure flashbacks, cuts that jump through space and time, image driven narrative, abrupt emotional shifts, literary and cultural references, meaningful background activity such as TV dialogue, and quick juxtapositions of highly charged meanings. These innovative traits make the film challenging despite the interesting ideas, beautiful images, excellent soundtrack, and superior acting. Fortunately our attention is rewarded in many ways. In fact, every time I see the film I encounter something new and make new connections. But in this essay I want to focus on how the film empowers us to think and feel deeply about various conditions that both prevent and enable human flourishing. Hopefully my analysis will contribute to the growing awareness that the film deserves far more respect than it often receives.

The Gravity of Vice

One thing that is made clear early on in the film is that the physically fragile Mr. Newton struggles with our planet’s gravity. He struggles to walk down a mountain after first arriving in New Mexico (fittingly nicknamed “the land of enchantment”), he asks his driver to keep it to 30 miles per hour, and he faints, bleeds from the nose, and vomits when an elevator accelerates too quickly. But there is another gravity represented in the film, something we might call the gravity of vice. This gravity is expressed through a network of influences that make us worse people and threaten to ground our lofty aspirations. Let’s take a look at this network in relation to the central characters, namely, Newton, his lover Mary-Lou (Candy Clark), his scientific advisor Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), and his exclusive business partner Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry). After doing so we can look at ways the film suggests we can escape, or at least fight, this gravity to some extent.

Alcohol and sex addiction

Alcohol is a powerful presence from the beginning to the end of the film. The first human Newton encounters after his arrival is a homeless alcoholic. Newton, initially a lover of water who can’t seem to drink enough of what he sees as a priceless resource, ends up becoming an alcoholic just like Mary-Lou and Bryce. Indeed, the film concludes with him passing out. Given this central role, David Bowie is surely right when, in The Criterion Collection edition commentary, he points out that alcohol can be considered a main character in the film.

Moreover, the film emphasizes the powerful role of libidinal desire through Bryce whose sex addiction leads him into countless adulterous affairs with his students. And we see the close connection between alcohol and sex in this exchange between Mary-Lou and Newton that comes later in the film:

Mary-Lou: What happens to you when you drink?

Newton: I see things.

M: What things?

N: Bodies.

M: Bodies? Women?

N: And men.

M: Men! Men? Mmm! Mmm! Bad boy!

And sure enough the two go on to drink and have wild sexual relations with gun play. These relations are in strong contrast to their initial sexual experiences which are sober, tender, and loving.

Suspicion

At various points in the film Newton says “don’t be suspicious” and plenty examples of the suspicious nature of humans can be found. Those who are suspicious of Newton include the first woman he meets at the pawn shop (who also has a gun in a drawer showing her suspicion of customers), the police officers who see him pull up in his limousine in New Mexico, Mary-Lou who asks if he is “hiding out,” Bryce who thinks Newton might be funding the development of a weapon rather than a space craft, Farnsworth’s partner Trevor (Rick Riccardo) who says of Newton “I don’t trust him,” and the scientists who believe he is a fake. There are other examples as well. Bryce tells his initial boss Professor Cannuti (Jackson D. Kane) about the innovative practices of World Enterprises and Canutti responds: “If you can’t spot a piece of bullshit commercial publicity when you hear it you’re even more naive than I thought.” Bryce then goes on to say he believes he will get a job with World Enterprises and Canutti says “I believe you won’t.” Mary-Lou says “Thank you. Merry Christmas” to the clerk at a liquor store and receives a cynical “uh-huh.” In a moving reflection she says to herself “I know I’ll never be like a character in a story. I’ll just be like everybody else. Well, maybe, maybe, maybe. I don’t know.” And even Newton refuses to leave his revolutionary designs with Farnsworth overnight. He says: “It’s not that I don’t trust you.”

These drives, addictions, and suspicions are ways the gravity of vice manifests itself through individuals. But the film also suggests a set of cultural factors that contribute to vice as well. Here are a few:

Mindless education

Bryce compares the university in which he initially teaches to a mindless computer. He tells Canutti “these kids are bored. They’re bored with you and these f***ing textbooks. They’re five years out of date. I mean what they need is some real stimulus. Ideas to pursue.”

A corrupt and interfering government that violates privacy

The film depicts a controlling government committed to maintaining a form of predictable change that lacks the innovation and uniqueness of World Enterprises. We hear a top level official say “We’re determining the social ecology. This is modern America, and we’re going to keep it that way.” His accomplice Peters (Bernie Casey), who is charged with taking over World Enterprises by violence if necessary, tries to reason with Newton’s partner Farnsworth as they walk while being observed from a distant roof top. But the latter simply says: “Frankly, what you’re suggesting sounds like interference.” Peters asks him to reconsider and adds that “The world is ever-changing, like our own solar system…and a corporation the size of yours has a duty to recognize that fact.”

But what form of change does our solar system possess? The kind whose novelty occurs within a system of cycles that can be predicted. After the government takes over World Enterprises, we find out that Professor Canutti has, unsurprisingly, been appointed “special adviser to the new administration on matters of economic development in the chemical industry.” He is asked on a TV show: “Are there any major new developments that have taken place recently, Professor?” Canutti responds: “Well, as we all know, a giant corporation, which had become a household word in this country…ran into financial difficulties. The main reason for this was the corporation relied heavily on that two-headed monster: Innovation. Now, the American consumer can assimilate only so many new products in a given period of time.” Of course, this may be true to some extent. Perhaps American consumers, indeed perhaps human beings in general, can only handle so much innovation. But what we really seem to have is an educator and government official offering propaganda for the social ecology that works best for those in power. Take note that in the film it is unclear who those in power really are. There is a mysterious observer who watches Newton’s initial fall to earth as well as his final fall into alcoholism. Is he part of the U.S. government? Some other government? No government at all? We don’t know. And this mystery works well with the theme of fate: like the inscrutable Fates who were above even the Gods in Greek mythology, the observer seems to be above it all as he calmly oversees the failure of Newton’s real challenge to the established system of power. Of course, this makes us think about to what extent we, too, are constantly being watched.

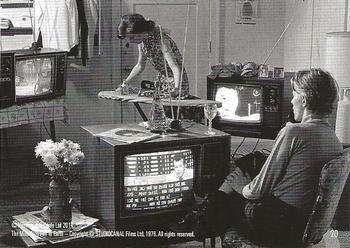

Psychologically detrimental television programming that doesn’t add up to much understanding

We should note that Canutti’s interview is on television which is a topic addressed throughout the film insofar as Newton, after moving in with Mary-Lou, becomes obsessed with it to the extent that he watches multiple TV sets at once. As a result, he begins to feel overtaken by images of nonsense, sex, and violence and screams “Get out of my mind, all of you! Leave my mind alone.” But despite all his TV watching – both on our planet and his as well – he doesn’t fully understand anything. He tells Bryce: “Television. The strange thing about television is that it doesn’t tell you everything. It shows you everything about life on Earth but the true mysteries remain. Perhaps it’s in the nature of television. Just waves in space.” This point can be generalized and applied to the other means of communication as well.

Corporations that commodify our lives, create radical dependencies, establish monopolies, and generate waste

World Enterprises Corporation itself can be seen as part of the problem insofar as it seeks to make life easier for everyone. Take, for example, their advertisement for a revolutionary form of film: “We help you to a better life. W.E. Film is self-loading, self-focusing, self-exposing. Self-developing. No light necessary. Is there a malfunction? We do it for you.” This effort to establish an ethos of doing as little as possible is fundamental to many corporations. Such an ethos is problematic since achieving great things requires hard work and radical dependencies undermine autonomy. We also can’t overlook the fact that World Enterprises seems to have taken over a wide array of markets. Have they monopolized those markets? Put tremendous numbers of people out of business and work? Finally, as Newton is preparing to blast off, we hear a television announcer say: “There’s widespread feeling that Mr. Newton’s latest experiment is wasteful” and that it doesn’t “result in any special benefit to the nations of this Earth.” This raises a common concern about corporations, namely, that they all too often use workers, consumers, and natural resources primarily for their own benefit. It certainly makes us wonder about the current “space tourism” being undertaken by incredibly wealthy figures like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. Moreover, the widespread use and production of commodities creates waste that pollutes the earth. We see a lot of this waste when Newton first arrives on earth in the form of an abandoned mill, garbage in the river, and old trains:

Soon after their initial encounter Mary-Lou tells Newton: “You know, this [the earth] is a very unhealthy place. Water here is all polluted. They put all kinds of chemicals in it to keep people from gettin’ sick. It’s a very unhealthy place.” And Newton’s memories of his planet raise grim concerns about ours as Graham Fuller, in his excellent Criterion Collection essay on the film, points out:

“Newton, of course, is not only from the “ancient time” of Blake’s “Jerusalem”—which he sings distractedly in Mary-Lou’s church—but also from the future. His memories of his planet could certainly be of Earth centuries (or less) after the events depicted in the film. Thirty years after Roeg filmed The Man Who Fell to Earth, over six weeks in July and August 1975, mostly around Lake Fenton, in New Mexico, it seems eerily prophetic of Earth’s own fate should global warming remain unchecked. Should we seek “outside” help, as Newton does? Roeg has that base covered: when Bryce apologizes to Newton for the way he has been betrayed and corrupted on Earth, Newton says a visitor to his planet could have expected the same treatment. The idea that human nature is the same the universe over, even when it’s nonhuman, is a bitter cosmic joke. But the joke doubles back on itself, because Newton’s planet is our own.” (read the whole essay here)

Superficial religion

Going to church, which strikes Newton as outlandish, is something Mary-Lou values. But she describes it more as a psychological crutch than a living faith: “It’s a real good church. You won’t feel out of place. Makes me feel so good. Gives me something to believe in. Everybody needs that – a meaning to life. I mean, when you look out at the sky at night…don’t you feel that somewhere out there…there’s gotta be a god? There’s gotta be.”

One integrated way to interpret all these factors is this: cultural practices like mindless education, governmental control, idiotic television programming, corporate commodification, and superficial religion have the potential to generate individual vices, which, in turn, can help strengthen those practices. This feedback loop is the gravity that threatens to ground our efforts to transcend the limitations of vice, acquire virtues, and actualize human potentials.

At one point Bryce, the morning after having yet another sexual experience with one of his students, picks up an art book (published by World Enterprises of course) sent to him by his daughter who, it can be surmised, he doesn’t see very often. In flipping through the pages, he pauses to read – and Roeg admirably allows us time to read it as well – an excerpt from W.H. Auden’s poem Musée des Beaux Arts (1938) which is accompanied by Bruegel’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus to which it refers. The full poem reads:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1560)

Auden’s wonderful expression of suffering according to the old masters might seem to capture the meaning of the film as well. To be sure, there are miraculous births and martyrdoms from time to time. And everyone may be a little interested in amazing things. But overall we have somewhere to go and sail calmly by. Of course, this might not be the worst thing in the world. There can be something comforting in the realization that the widespread suffering in the world, which seems to be a cause for despair, is put in its place and cannot paralyze us: we might, like those in Bruegel’s painting and the characters in the film, carry on in a kind admirable stoicism. We might even be decent enough people despite the gravity of vice that neutralizes our sensitivity to transcendence and keeps us firmly earthbound.

The Persistence of Virtue and Aspirations

But this interpretation is not comprehensive enough. For the film also presents us with plenty of virtues, aspirations, and accomplishments. Let’s look at some examples.

We see Mary-Lou exhibit great kindness when she helps Newton, a stranger to her at the time, upon his collapse in the elevator. She literally and symbolically lifts up the fallen man. As we have seen, she is aware of the dangers of pollution. She seems to have a sincere wonder about God despite her superficial means of expressing it. She appreciates stargazing and looking through a microscope. She appreciates beauty when, after going out into the country with Newton, she exclaims: “Lord, I never knew America was so beautiful. This is beau-ti-ful.” She tries to keep lines of communication open with Newton when their loving relationship starts to deteriorate due to his to drinking and TV obsession. And perhaps most importantly, she tries, although understandably doesn’t completely succeed, in making love to Newton after he has revealed his terrifying alien nature to her. She courageously engages in, to invoke the name of a wonderful David Bowie song, loving the alien rather than shutting out or attacking that which is different.

Bryce, too, has many good traits. He sees what is wrong with education and admires World Enterprises for their novel approach of “dumping computers” and “installing human beings.” He tells Canutti: “Want to know why? They want to bring back human error because that’s the way you get new ideas – by making mistakes. Back to man and his imagination.” This interest in reform leads to a reform of his libido:

“For a whole year I concentrated on two things. F***ing and World Enterprises. It was neck and neck. Suddenly, I got this letter from Farnsworth. I’d landed a job in the research department of the fuel division. Strangely, after that I gradually began to lose my interest in 18-year-olds. I don’t know what happened to me. I’m not sure. But my mind had developed a libido of its own and I didn’t need the stimulation of legs and so forth. Last time I remember feeling so exhilarated was 10 years back when I’d been experimenting with heat photography. It came to nothing, of course, because academia got in the way. But this time I knew I was gonna be given a proper chance. And you know how I knew that? Because I had faith in myself. What I didn’t know then was someone else had faith in me as well.”

Nathan in the process of having his libido redirected from a sexy body to the astonishing self-developing film of World Enterprises!

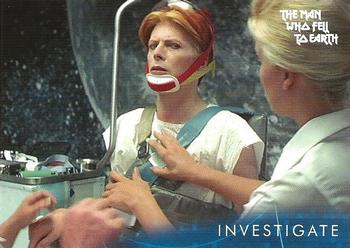

In Karl Marx’s terms, Nathan was alienated from his creative potentials and, as a result, was engaging in sex as a substitute for the actualization of meaningful labor. But when he lands a research job with World Enterprises he breaks his addiction. Instead of having his ideas dismissed by his old boss, his new boss Newton says: “I want to show you this because I value your contribution to my work.” We should also note that he is obviously intelligent, cares for his daughter despite his separation from his wife, and doesn’t appear to be materialistic. His observation “I believe Christmas is less commercial this year” towards the end of the film suggests this. And he is only committed to working with Mr. Newton if his space program is not going to manufacture weapons. Of course, in the end he does end up betraying Newton despite Newton’s faith in him. He photographs him with an X-ray and helps turn him over to the government where he is subjected against his will to torturous scientific experimentation. But he still seeks out Newton after his disappearance and finds him. He doesn’t forget about him and go on living in denial.

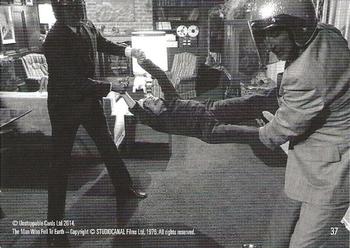

Oliver Farnsworth, while enamored with power and wealth, is also quite courageous in his effort to stand up to the government who he sees as interfering with the innovation of World Enterprises. He also genuinely cares for Newton and, against the wishes of his partner Trevor, is loyal and stays with him to the end. Unfortunately, his courage and loyalty lead him (and subsequently Trevor) to literally fall to earth when he is thrown out of his high-rise apartment by government thugs.

And Newton himself, while an alcoholic who became a bit too enamored with power, material goods, TV, and a sexist domestic set up, seems to keep most of his good nature intact. Despite betrayal, governmental manipulation, and torturous scientific examination he is not embittered.

Consider these passages from the last scene of the film:

Bryce: Don’t you feel bitter about it – everything?

Newton: Bitter? No. We’d have probably treated you the same if you’d come over to our place.

This is consistent with an earlier claim he made to Mary-Lou, namely, that he simply cannot hate others. He also asks how Mary-Lou is and expresses his hope that she is not lonely (Bryce, however, doesn’t tell Newton that he is now in a relationship with her). He even offers Bryce, the man who betrayed him, money should he need it! Newton is certainly an imperfect and vulnerable man. In fact, he tells Mary-Lou that is not a good man. But his care, generosity, and lack of hatred and bitterness also make him a savior figure who, despite trying to make others less hateful and bitter, suffers at their inconsiderate hands.

So we see that the central characters are by no means completely vicious or indifferent to greatness: they all have some virtues and aspirations which, despite their many vices and failures, allow them to accomplish many things. Perhaps, then, we should see the film’s vision of the human condition as one in which we, rather than being stoic and relatively indifferent to wondrous things as the passing ship in Auden’s poem, are indeed capable of great things but, given our fallible state beset by so many dehumanizing forces, can only ascend so far and accomplish so much. To put it differently: many of us want to love the alien and get closer to it but, should it really appear in all is strangeness, chances are we will recoil. This reading does justice to the complexity of the film and can be seen as an antidote to views of the world that are hopelessly pessimistic and superficially optimistic. It appears to offer us a melioristic view of the human condition that says we can, in certain situations, make things better.

Some Prescriptions

Is this where we should leave it? Perhaps. But the question arises: how much better can we make things? In many ways the film offers us a clear answer: not much better at all. But I think the film also allows us to infer a set of prescriptions for improving things far more than we think is possible. Some are fairly obvious given the above analysis. For example,

(1) We shouldn’t drink so much! As Peters puts it: “You know, if all of you drank less, we’d get better results. Take my advice and stick to mineral water. Keep your perspective.” A similar prescription would go for other potentially addictive pursuits such as taking drugs, shopping, having sex, etc.

(2) We should follow Mary-Lou’s exhortation to Newton to turn off the televisions and talk. This is something we can all take to heart in our screen-addicted an increasingly isolated cultures full of incoherence, sound bites, cliches, impersonal modes of expression, and so on.

(3) We should resist excessive corporate and government control (although in the film the government seems to be a corporation), stand up for our rights, and do our best to prevent ecological disaster both locally and globally.

(4) We should cultivate more critical thinking and imagination in education, religion, and elsewhere.

But there is another set of four closely related prescriptions which are less obvious and warrant some discussion. And I think these are less about what we should do for reform and more about developing certain attitudes or capacities that can help us engage in such reform. I don’t maintain all these prescriptions are explicitly addressed in the film. I am taking what I take to be hints and elaborating on them a bit. And I certainly don’t claim they are completely convincing or comprehensive. But I do think they may help us improve in unexpected ways.

Have more faith and don’t be so suspicious

As we have seen, Newton thinks humans are excessively suspicious and periodically says “don’t be suspicious.” In the film the antidote for this excessive suspicion seems to be faith. When Nathan is overcoming his sex addiction he comes to have faith in himself in large part because, as he admits, Newton had faith in him; Newton says he trusts both Bryce and Mary-Lou once they know about his alien nature; Farnsworth has faith in Newton whose schemes are all too often absurd to him but generate astonishing financial profits; and Mary-Lou, who had no faith that her life would be part of a unique story, ends up being part of a truly astonishing one indeed. The film suggests faith can lead to unexpected innovations. Here we might bring in an insight from the American philosopher and psychologist William James who, in his essay “The Will to Believe” (1896), claimed “faith in a fact can help create the fact”: “There are, then, cases where a fact cannot come at all unless a preliminary faith exists in its coming. And where faith in a fact can help create the fact, that would be an insane logic which should say that faith running ahead of scientific evidence is the “lowest kind of immorality” into which a thinking being can fall.”

And the film certainly helps us be on the lookout for those who would crush this faith under the weight of their suspicions. When Newton is preparing to blast off into space, a television announcer rightly says: “There’s no parallel to be found with what this man has done and is now doing. It’s difficult to compare him with anyone. He is unique.” Of course, after he is captured and examined, a scientist confidently and cheerfully tells him: “Don’t worry, Mr. Newton. You’re perfectly normal.” Haven’t we all met this kind of person who is more than happy to assuage our worries by demonstrating our normality? More than happy to tell us to live a life in service of perpetuating the all too often oppressive norms? Such people may not see uniqueness and potentials for innovation because they don’t believe such things exist. Thus we have a nice slogan which appears on one of the more interesting posters for the movie: “You have to believe it to see it.”

Try to remember

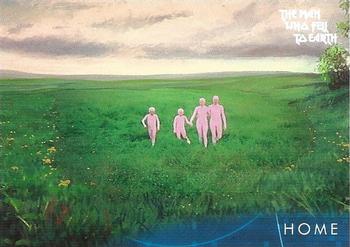

One of the interesting things about the film is how it handles memory. In one of Roeg’s most powerful sequences, Newton is looking at a running white horse from the moving car. He then imagines his family amidst a green pasture instead of the barren home he left:

As the images pass we hear the Kingston Trio’s beautiful version of the song Try to Remember. Here is the passage from the film:

Try to remember

The kind of September

When life was slow

And oh so mellow

Try to remember

The kind of September

When grass was green

And grain so yellow

Try to remember

The kind of September

When you were young

And a callow fellow

Try to remember

And if you remember

Then follow

Follow

Newton then dreams of his family and a train on his home planet. He is suddenly awakened by Mary-Lou who excitedly shares her own train memory (this passage was improvised by Candy Clark):

“Tommy. Tommy, look. A train. I like trains. I remember when Mama used to put us on the train. I was about 10. And we’d go to Oklahoma City to visit Granny. The trains were really nice then. They had concession stands and they would sell, uh, magazines and candy bars and sodas. And then, about six years later I rode the train again and the concession stands were gone. There weren’t too many people on the train. There weren’t any dining cars, and the seats were all shabby. It’s a shame. I used to like trains.”

As Mary-Lou is talking he envisions himself boarding the alien train and leaving his family. This innovative sequence of memories and associations, which resonates with earlier scenes that include trains, creates a melancholic sense of the passage of time and its losses. But it also seems to suggest that we try to follow some of our memories, however melancholic, in order to be revitalized. Mary-Lou might really connect with her 10 yr. old self. Newton might really connect with his former life as a father. In doing so they might carry something inspiring from the past into the present and future. What memories can we follow into a better world?

Acknowledge our fallibility in order to progress

It is easy, after encountering some of the more depressing aspects of the film, to overlook that our fallibility, our radical capacity to be mistaken about so much or perhaps everything, offers us a good reason why we shouldn’t be pessimistic. In the final scene we encounter this exchange:

Bryce: Is there no chance then?

Newton: Of what? Of course there’s a chance. You’re the scientist, Dr. Bryce. You must know there’s always a chance.

Science is a method which is inherently fallible. This means that all results of the method are open to change in light of future experiments. We can know for certain that some hypothesis is wrong. But we can never prove something definitely right. So when Bryce asks whether there is hope, Newton simply shows him that, given his commitment to science, there is always hope since we can never dogmatically rule out in advance novel discoveries that might change our situation for the better (one might contrast this open-minded attitude of science to the mocking and condescending scientists who experiment on Newton). We should also note how mistakes can drive innovation. We saw this above with Bryce’s comment that World Enterprises wants to “bring back human error because that’s the way you get new ideas – by making mistakes.” And fallibility is crucial to moral self-examination as well. There is a great scene when we see the government official Peters at his home after the government take over of World Enterprises. He has a pool, a beautiful wife, a nice relationship with his children, and, given the pictures in his bedroom, appears to have had an impressive past as a football star and military man. We get a strong sense that the condition for the possibility of his American Dream is injustice and murder (Roeg seems to symbolize this by juxtaposing Farnsworth’s fall from the building with Peters’ dive into his pool over to his wife). He seems to sense this when, after having tucked his kids into bed, he has this exchange with his wife (Claudia Jennings):

Peters: I wonder if we do and say the right things.

Wife: To the children?

Peters: No. Everything.

Peters experiencing some doubts within the American Dream

One gets the sense that Peters is only going to take his self-examination so far. But he is wondering and his sense of fallibility that applies to everyone – he says we – and everything is bound to help us improve morally and in many other ways as well.

Try and see our lives from the point of view of eternity

Bryce and Newton have an interesting exchange in the desert in which Bryce boldly says “I’m a scientist” and Newton responds “Well, I’m not a scientist. But I know all things begin and end in eternity.” Newton, unlike the other characters, doesn’t age at all over the course of many years (this, incidentally, is the strongest reason against the view that he really an eccentric and ingenious human rather than an alien). He can see back into the past and forward into the future. He even has telepathy and can bilocate. As a result, there is a sense of eternity about him. He seems to have one foot within the limits of time and another foot outside those limits. Can we, somehow, relate to this condition? I think the film suggests at least two ways.

Screenwriter Paul Mayersberg, in his Criterion Collection edition interview, points out that our interest in time comes primarily from our interest in our death. Since Newton is never a day closer to his death, he is not very interested in time. Now obviously all of us age. So perhaps we would be unable to identify with Newton’s outlook. But Mayersberg says we do see this lack of concern for time in “mystics, and spiritual people, or even soldiers” since they are not concerned with their death. I think the film offers us an occasion to see our lives more sub species aeternitatis – from the point of the view of eternity. How? Primarily by seeing ourselves through Newton’s eyes. Mayersberg points out that, in the film and unlike the book, Newton “knows he is going to be discovered and he keeps saying to Bryce don’t be suspicious, don’t be afraid.” Newton is a man that “knows everything ahead of time” and knows, like Jesus, he will be betrayed. We are all, of course, denied such foreknowledge. In The Criterion Collection edition commentary, Buck Henry discusses Farnsworth’s thick glasses in relation to the theme of lacking sight in the film: we can only see so much and the film refuses to offer us all the connections we need to completely understand what is going on. This connects nicely with the thoughts on television discussed above.

But I think the film inspires us to take a more comprehensive view of our lives that helps expand our consciousness past its narrow set of concerns. In taking such a view, we may come to see a kind of necessity in their unfolding. Such a view might help us more readily accept the limits, failures, disappointments, betrayals, contingencies, absurdities, and so on we are bound to experience. It might also help us reduce many of our cravings, fears, and unrealistic expectations. Here I am reminded of Spinoza (1632-1677) who, in his Ethics (part V, proposition 6), writes:

“The more this knowledge that things are necessary is concerned with singular things, which we imagine more distinctly and vividly, the greater is this power of the Mind over the affects, as experience itself also testifies. For we see that Sadness over some good which has perished is lessened as soon as the man who has lost it realizes that this good could not, in any way, have been kept.”

Steven Nadler offers a helpful elaboration in his Spinoza entry for the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“What we see when we understand things through the third kind of knowledge, under the aspect of eternity and in relation to God, is the deterministic necessity of all things. We see that all bodies and their states follow necessarily from the essence of matter and the universal laws of physics; and we see that all ideas, including all the properties of minds, follow necessarily from the essence of thought and its universal laws. This insight can only weaken the power that the passions have over us. We are no longer hopeful or fearful of what shall come to pass, and no longer anxious or despondent over our possessions. We regard all things with equanimity, and we are not inordinately and irrationally affected in different ways by past, present or future events. The result is self-control and a calmness of mind. Our affects or emotions themselves can be understood in this way, which further diminishes their power over us.”

Now one may not agree with Spinoza’s completely deterministic view of reality that denies free will and would, in helping remove fear from our heart, remove hope as well. But we can certainly accept that many aspects of our lives are necessary and, in doing so, come to see them more from the point of view of eternity.

Another way the film suggests we can relate to eternity is through contemplating the heavens. When Mary-Lou and Newton first move in together, Newton gets her a “prize”: a telescope. Mary-Lou is overjoyed, and says “You saw me looking in that magazine, didn’t you?” Here we can infer Mary-Lou’s interest in stargazing which can be connected to her earlier comment that looking at the stars makes her feel there is a God. Humans love to look at the heavens which invoke the beautiful, the sublime, and the divine. And when we don’t have ready access to the kind of wide open skies shown in the film, we enjoy pictures of them. It is interesting to note that pictures of stars or skies are present in Canutti’s office, Farnsworth’s office, and the room in which the experiments on Newton are conducted. We even see the picture from Farnsworth’s office hanging in Newton’s little desert cabin despite the fact that real sky is just a glance away.

The Milky Way photographed by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope

Of course, it could very well be that, despite these experiences that seem to elevate our soul from the confines of the earth, our fate is just what Mary-Lou says Newton’s fate will be: “You’re gonna die like an animal. Just an animal, a stupid creature.” But if we follow her earlier musings on God we might agree with the renaissance Platonist Marsilio Ficinio (1433-1499) who, in his Platonic Theology (Book X, Chapter II), writes:

“In justice, the rational soul should be called a kind of god, or a star ringed with cloud, or a daemon: not an inhabitant of the earth, but a guest. Guest, know yourself, know you are a citizen of a heavenly country, a citizen born to contemplate things celestial. Remember, if your end is contemplation, that your life should be enriched and perfected by contemplating. But since from this contemplating the body’s life in a way loosens its hold, it follows that in this very weakening and death of the corporal life, your life grows not fainter but stronger.” (translated by Michael J.B. Allen)

Mr. Newton, despite his temporal concerns, contemplates the heavens to the tune of Gustav Holst’s Venus, the Bringer of Peace (1914-1917) which expresses the descent of eternal beauty into time (listen here).

In contemplating the heavens we might be reminded that we are earthly guests separated from an eternal realm to which we are akin. We might then see the temporal struggles of our world less as occasions for despair and more as opportunities to grow spiritually in order to be prepared for our true celestial home. Such is, of course, one of the enduring messages of so many religions and philosophies over the centuries.

The practical significance of adopting one or both of these views is this: in coming to see things more from the point of view of eternity we might, like Mr. Newton, have our consciousness expanded and free ourselves from the bitterness and hatred that all too often accompany our narrow, temporal concerns. And this, in turn, might help us individually and collectively accomplish far more than we thought possible.

It is interesting to see how these four prescriptions for reform can be related. Perhaps, in having less suspicion and more faith, we can be less dogmatic and more experimental. This would feed into our sense of fallibility. Our ability to follow vitalizing memories might contribute to our faith and show us that our present circumstances aren’t as fixed as they may seem. And if certain circumstances are indeed necessary, an expanded sense of time and a sense of the eternal just might help us accept them without those damaging emotions that thwart our efforts to alter conditions that can be changed. And, when we think about how these four prescriptions connect to the earlier four – less drinking and more talking, thinking, and civic engagement – then we can make further connections which, in turn, link to the many ideas expressed in what I called the network of vice. In any case, the film presents a web of insights that reward our inquiry into their significance. Part of the fun of watching it is discerning and unraveling this web over the years.

Conclusion

We have seen that The Man Who Fell to Earth can be interpreted as a meditation on the conditions that both prevent and allow humans to flourish. We have seen that the film offers us a view of ourselves as creatures of vices that, while capable of some longing for innovation and uniqueness, are mostly operating within a cultural system whose gravity keeps us earthbound and indifferent. But we also saw plenty of virtues, aspirations, and accomplishments that resist this reading. Perhaps the most sensible view of the film is that it depicts both these tendencies in the human condition and gets us to think about them in relation to a wide network of biological, psychological, political, educational, religious, and technological influences. But, as I suggested in the last section, I think the film does more: it suggests a set of strategies that might help us ameliorate our condition far more than we thought possible. In doing so it might actually be more upbeat than it first appears. This reminds me of an exchange Bryce and Newton have in Newton’s spaceship:

Bryce: Well, anyhow, uh…”Per ardua ad astra.”

Newton: I beg your pardon?

Bryce: That’s Latin.

Newton: Latin?

Bryce: You must know that in England. Royal Air Force…their motto.

Newton: Yes.

Bryce: “Per ardua… ad astra.” Through difficulties, to the stars.

But perhaps it is wiser to say “through difficulties, closer to the stars.” For we are all, like the film’s characters, bound to be beset by forms of alienation no matter what we do. Perhaps we persist in pursuing the unattainable. Perhaps we live incognito. Perhaps we are perceived as freaks because of how we look, our interests, or where we come from. Perhaps those with whom we have relationships make us outcasts. Or perhaps we can’t connect with our family and home. Whatever the case may be, alienation is bound to be there even if it appears in the form of Mary-Lou’s wigs, fake nails, fake eyelashes, and hair dye.

And yet, in the end, this fact may be precisely what truly enables us to transcend as much as possible. In The Criterion Collection commentary, Roeg points out that he was trying to make a “disquieting and alien” film in which “even the familiar is strange…even the familiar is strange when looked at in another way, thought about in another way.” Newton, contemplating trains in New Mexico, says: “They’re so strange here – the trains.” We, of course, might think of the train on his home planet as strange…perhaps even low budget as well! But the film offers us an opportunity to really look at our trains as if for the first time. The aspects of Japanese culture in the film, such as the haunting music courtesy of Stomu Yamash’ta, the majestic Torii gates and minimalist style of Newton’s home, and the Kabuki sword play in the restaurant, may strike many viewers as alien indeed. But such aspects may allow them to reflect on how strange their own music, drama, and architecture might be to others. There is the wonderful scene when Newton perceives a group of pioneers, presumably from the 1800s, and they, in turn, see his moving limousine. They are absolutely astonished at the site of something which, for us, is so common. But the film invites us to see our cars through their wondering eyes. And we shouldn’t overlook how the film’s very fallen world nonetheless includes a happy interracial marriage (Peters is married to a white woman) and a happy gay couple (Farnsworth and Trevor) which may strike some as different and, in doing so, may help them reflect on their own relationships and conceptions of normality. The film’s material allows us to keep going: isn’t TV simply bizarre? Aren’t adults who do nothing but hang around and drink like aliens? Isn’t Christmas from another world? Aren’t the “dark satanic mills” (Blake) of industry that befoul the majestic landscape of earth something incomprehensible? And so on. But the key is that, in helping us see the familiar as unfamiliar in such a ubiquitous way, Roeg’s uncanny film helps us see that we are all vulnerable beings who, in one way or another, have fallen to earth. As Roeg also says in the commentary, “we are all strangers in a strange land…even in our families we are alone.” If we take this insight to heart then we just might connect with each other in unexpected ways that overcome some of our alienation, reduce our need for vices, and realize more of our daydreams.

© Dwight Goodyear 2021

For my post that explores Immanuel Kant’s account of the sublime, which resonates with the above insights about stargazing, go here.

For my post on Soren Kierkegaard’s conception of demonic evil, which resonates with some of the insights about vice and self-destruction above, go here.

For my post on William James’ melioristic account of heroism, which illuminates some insights about striving for greatness mentioned above, go here.

For more on fallibilism, go to my posts here.