175. Medusa and R.D. Laing’s Divided Self

R.D. Laing

In his book The Divided Self (Penguin: 1969) the Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing (1927-1989) attempts to existentially and phenomenologically, rather than biologically and clinically, understand “the schizoid individual” or “an individual the totality of whose experience is split in two main ways: in the first place, there is a rent in his relation with the world and in the second, there is a disruption of his relation with himself” (17). Such a person cannot be at home in the world and cannot feel unified with others; rather, he exists in an ongoing state of alienation that gives rise to anxiety and self-defeating attempts to escape this anxiety. To be sure, most of us do not experience the extreme “self-splitting” (chapter 5) and “unembodiment” (chapter 4) which Laing claims to be so characteristic of schizoid individuals. Nonetheless, we do experience the anxiety of alienation at some time or another. So I think his account is relevant to all of us and can help prevent our alienation from growing in unhealthy ways. In this post I will explore his ideas about the anxiety of petrification in relation to his interpretation of Medusa since, according to Laing, the “Myth of Perseus and the Medusa’s head…is referable to this dread” (110). In particular, I want to explore his suggestions for helping those who adopt a Medusa-like stance towards others. Let’s begin with Laing’s take on Medusa which differs from more well-known feminist and psychoanalytic interpretations:

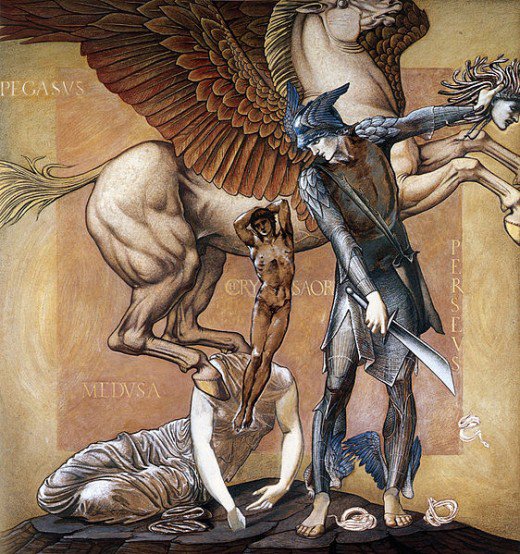

“Petrification, we remember, was one of Perseus’ methods of killing his enemies. By means of the eye in Medusa’s head, he turned them into stones. Petrification is one way of killing. Of course, to feel that another person is treating or regarding one not as a person but as a thing need not itself be frightening if one is sufficiently sure of one’s existence….but to the schizoid individual every pair of eyes is in a Medusa’s head which he feels has power actually to kill or deaden something precariously vital in him. He tries therefore to forestall his own petrification by turning others into stones. By doing this he feels he can achieve some measure of safety.” (76).

Here Laing is building off of Jean-Paul Sartre’s account of “the look” in Being and Nothingness (for my notes on Sartre’s existentialism, go here). Sartre argues, following Soren Kierkegaard, that we are free beings who find our radical freedom burdensome given the anxiety to which it gives rise. Typically this anxiety is in relation to choosing from among possibilities about our future and taking responsibility for our past. But Sartre also emphasizes we are anxious about having our freedom compromised by others. We may experience this compromise viscerally when we are looked at. In some cases the look of others can cause us to act in ways we think others would want us to act. In those moments we feel our freedom momentarily dissipate and, rather than existing for ourselves, we exist for others. Picking up on Laing’s Medusa metaphor, we can say that in the presence of the look we feel as if we have become depersonalized by Medusa’s petrifying gaze.

Medusa by Caravaggio

Laing asserts that a “partial depersonalization of others is extensively practiced in everyday life and is regarded as normal if not highly desirable. Most relationships are based on some partial depersonalizing tendency in so far as one treats the other not in terms of any awareness of who or what he might be in himself but as virtually an android robot playing a role or part in a large machine in which one too may be acting yet another part” (47). This partial depersonalization is no doubt a function of our limited time and energy: seeing each other superficially allows us to conduct the superficial transactions we make in our lives. But a tendency towards more extreme forms of petrification can develop if we become anxious about “the look.” We may become more inclined to preemptively neutralize the look by casting a depersonalizing gaze first. This was the case with one of Laing’s schizoid patients who had “an inner intellectual Medusa’s head he turned on the other” (48) in order to avoid depersonalization. Such an intellectual Medusa might, for example, filter the living reality of others through a system of fixed labels and characteristics in order to compartmentalize, predict, master, and ultimately disregard them as dead. This, however, is problematic since “our relatedness to others is an essential aspect of our being…” (26). Indeed, without such relatedness our inner self “develops an overall sense of inner impoverishment, which is expressed in complaints of the emptiness, deadness, coldness, dryness, impotence, desolation, worthlessness, of the inner life” (90).

So becoming more like Medusa ourselves is a self-defeating solution for dealing with Medusa! Perhaps we might, as Perseus did, try to look at those who would depersonalize us indirectly on a reflective shield that makes their image bearable: perhaps a theory of their illness would do. In this case we wouldn’t be looking to kill but to safely strategize for survival. But there is another option.

Medusa, at least according to Ovid’s account of her life in his work Metamorphoses, was a beautiful young virgin who served as a priestess to the Goddess Athena. Unfortunately, she caught the eye of Poseidon who ended up raping her in one of Athena’s temples. Athena, rather than helping her servant, thought it appropriate to punish Medusa, the victim, by transforming her into someone so ugly nothing could look at her without turning into stone. The details of the story are less important than an insight to be gained from it: people who objectify have often gone through traumatic objectification and, as result, may think it wise to hide their beauty from us.

This interpretation offers us a task more difficult, perhaps, than Perseus’ own burden: look directly at Medusa and, rather than shying away from her ugliness and the suffering from which it sprung, seek to enhance the beauty and freedom her exterior hides. Take note that in one version of the myth two things sprang out of Medusa’s dead body: Pegasus, the winged horse which can symbolize freedom, and Chrysaor, a giant wielding a golden sword which can represent courage. Can we see such powers even in those who would take away our freedom and courage? If we can then we just might relax their Medusa-like glances. Laing notes that “what the schizophrenic is to us determines very considerably what we are to him, and hence his actions” (34). So if we choose to send out a very different type of ray from our eyes – one that enhances freedom in love rather than petrifying it in hate – we just might come to understand, as Laing mentioned above, the person “in himself” rather than a mere robot playing a role. After all, in place of understanding “we might say love” (34).

Unfortunately love, as much as hate, is feared by those who fear others: “If the self is not known it is safe. It is safe from penetrating remarks; it is safe from being smothered or engulfed by love, as much as from destruction from hatred” (164). But the love that is rightly feared by the schizoid individual is really a “purely intellectual process” rather than a “knowing how the patient is experiencing himself and the world, including oneself” (34). Only through such mutual existential encounters can people learn to develop a sense of who they are for themselves rather than for others. This is really the foundation for all other interpersonal growth since a “firm sense of one’s own autonomous identity is required in order that one may be related as one human being to another” (44).

R.D. Laing was, and continues to be even after his death, controversial and challenging. We might not agree with his radical claims and treatments given all we know know about, say, neurophysiology. But one thing is clear: he tried to make real contact with his patients and always presupposed, despite so called abnormal and even horrific behavior to the contrary, a common humanity. To be sure, thinking about others this way may prevent us from seeing causes for mental illness that have nothing to do with will and voluntary isolation. But such an existential orientation may, on the other hand, help us make progress that a more biological approach would thwart. In any case, I find his efforts to liberate humans in bondage inspiring and see his place as one of the great minds in the humanist school of psychology fully justified. For the official R.D. Laing site, go here. For an informative NYTimes obituary, go here. For Soren Kierkegaard’s account of evil that focuses on voluntary isolation and other ideas that influenced Laing, go here.

For my series of posts on Dracula, go here.

For my post on the cognitive and moral worth of Halloween, go here.