121. Soren Kierkegaard’s Theory of Demonic Evil

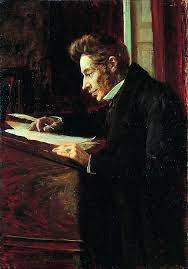

Soren Kierkegaard

Introduction

It is popular these days to think about evil from a scientific perspective that sees evil as, for example, a function of an improperly working brain. Such approaches typically remove free will and the more traditional parameters in which discussions of evil have taken place such as moral accountability, damnation, turning away from God, etc. These changes can be helpful since many actions once perceived as a function of free agency are indeed determined by brain functions over which we have no control. But in some cases these approaches may explain away, rather than explain, important aspects of evil we desperately need to understand. So it may be helpful to consider a view of evil firmly grounded in human freedom which has impressive explanatory power.

The Danish existentialist philosopher Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), via his pseudonym Vigilius Haufniensis (a Latin transcription for “the watchman of Copenhagen”), put forth a disturbing and ground-breaking account of demonic evil in chapter four of his eccentric work The Concept of Anxiety (1844). In this work he claims the demonic person has anxiety about the Good which means he is both repelled by, and attracted to, the Good. This anxiety gives rise to freely chosen defiant actions that seek to undermine the Good in order to be free from the anxiety it causes. This active defiance reveals that demonic evil is not evil for evil’s sake; rather, it a form of instrumental evil that seeks to accomplish something. Demonic defiance has three modes of interrelated behavior: shutupness or inclosing reserve, the contentless or the boring, and the sudden. In this essay I will explain these forms with the help of Kierkegaard’s writings, insights from other thinkers, and some examples from life and art. I will also show how each form has something self-defeating and inscrutable about it. Finally, I will discuss why, according to Kierkegaard, demonic evil exists and what we can do about it. I close with an extended definition of the demonic as a summary. I will be quoting from the Princeton edition of The Concept of Anxiety.

Shutupness

Kierkegaard notes that “The Good, of course, signifies the restoration of freedom, redemption, salvation, of whatever one would call it” (119). And these aspects of the Good can only come about through meaningful communication and disclosure. Thus the demonic person’s initial and fundamental strategy for defying the Good is to shut himself up with himself to avoid meaningful communication. Kierkegaard notes that this is the basic form of activity the demonic takes—a form of withdrawal from other people. He refers to this form as shutupness or inclosing reserve and notes that the demonic individual “becomes more and more inclosed and does not want communication” (124).

Francis Bacon, Figure Crouching (1949)

Since the expansive, communicating power of language is “precisely what saves” (124), the demonic person ultimately chooses to be mute in the sense of not revealing anything about himself. Shakespeare’s Iago offers a perfect slogan – I am not what I am – for this aspect of demonic evil in Othello, 1.1.66-67:

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at. I am not what I am.

As Harold Bloom points out in his book Iago: The Strategies of Evil (Scribner, 2018), this contrasts with God’s declaration to Moses in Exodus 3:14 —“And God answered Moses, I AM THAT I AM” — and Paul’s claim at 1 Corinthians 15:10 that “But by the grace of God I am that I am: and his grace which is in me, was not in vain: but I labored more abundantly than they all: yet not I, but the grace of God which is in me” (Geneva Bible). These Biblical quotations affirm both God’s authenticity and how God’s authentic grace can, in turn, make us more authentic. Demonic withdrawal is the opposite: what is shown is not authentic. Such deception is an initial way to thwart interpersonal relationships in order to remain alone.

The Self-Defeating Aspects of Shutupness

Kierkegaard asserts that a complete break with communication “is and remains an impossibility” (123) since selfhood, even evil selfhood, is oriented by God to have an other-regarding social orientation. This orientation can also be given a non-theistic justification. We might turn to evolutionary psychology for an account of our inescapable social nature. We might, as Agnes Heller points out in her book Immortal Comedy (Lexington, 2005), focus on how carnal desire can undermine attempts at complete closure: “The daemon is unreachable; he is moved neither by pity nor by love, and he is deaf to the claims of justice. But the body is something else again, going its own way, lusting, following a different obsession” (69). And we might emphasize the role of language as well. Ronald L. Hall, in International Kierkegaard Commentary: The Concept of Anxiety (Mercer University press, 1985), points out that Kierkegaard connects selfhood to language and that language “in its proper use presupposes a genuine community” (165). So the demonic self, if there is to be a self at all, cannot avoid language and the intersubjective action that language involves. This isn’t to say that the demonic individual can’t remain mute, talk to himself, and mime to the extent that, for all practical purposes, the person remains shut up. But complete isolation is incoherent.

As a result, we should expect that the goal of muteness may be thwarted by involuntary disclosures. The demonic individual, when confronted with manifestations of the Good, may become so anxious that he will unfreely disclose something he has hidden: some cruel remark, some spiteful glance, some odd bodily gesture will betray the weakness of his stronghold. Kierkegaard claims such disclosures will have an uncanny dimension since the demonic person will seem possessed like a dummy through which a ventriloquist—or perhaps even a legion of ventriloquists—is speaking (129). On such occasions we may come to understand what particular form of the Good someone is anxious about: love, dialogue, beauty, meaning, truth, trust, confidence in their own abilities, intimacy, and so on.

The Inscrutability of Shutupness

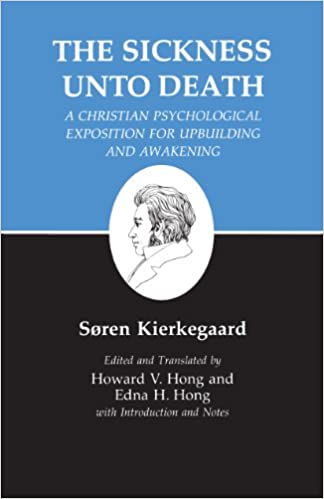

Involuntary disclosures may reveal something about the demonic person. But in many cases adequate understanding will elude us. Kierkegaard expresses this when, after discussing shut-upness, he writes: “However, I dare not continue further, for how could I finish even a merely algebraic naming, let alone an attempt to describe or break the silence of inclosing reserve in order to let its monologue become audible, for monologue is precisely speech, and therefore we characterize an inclosed person by saying that he talks to himself” (128). In The Sickness Unto Death (Penguin Publishing, 1989), Kierkegaard tells us that part of the problem is

“that the more spiritual the despair becomes, and the more the inwardness becomes a separate world for itself in reserve, the less consequence attaches to the external form under which the despair hides. But precisely the more spiritual the despair becomes, the more it attends with demonic cleverness to keep the despair enclosed in its reserve, and the more it therefore attends to neutralizing the externalities, making them as insignificant and inconsequential as possible” (104).

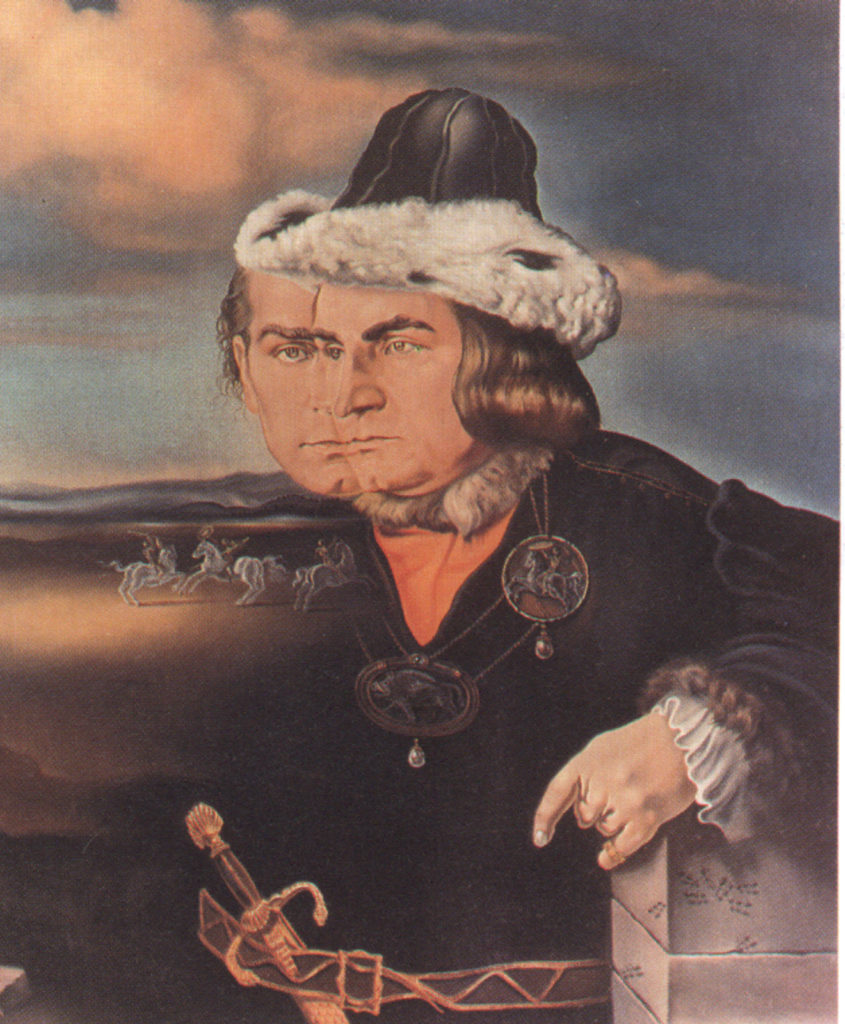

Salvator Dali, Portrait of Laurence Olivier in the Role of Richard III (1955) Dali masterfully captures Richard’s demonic nature hidden beneath his regalia and feigned indifference.

In the end we may have to accept that in some cases the demonic individual “is like the troll in the fairy-tale who disappears through a crevice that no one can see” (104). One thinks here of the many descriptions given by people who were acquainted with individuals who committed evil acts like “he was so quiet”, “we never knew much about him”, “who would’ve thought he’d do something like that”, “never really talked much”, “I can’t believe it”, and so on.

The Contentless or The Boring

The fact that the demonic individual’s reserve disappears into a crevice doesn’t imply he or she lacks all continuity with the world: he or she still talks and interacts. But this interaction, rather than being authentic, will seek to negate those aspects of the Good which, in speaking to our social nature, inevitably and continually generate anxiety. Such acts of negation seek to empty the world of Good content and the vitality it offers. Thus we have the second aspect of the demonic, namely, the contentless or the boring. Note that we are not dealing with people who want to open up and unify with others but, due to their anxiety, struggle and fail to do so. Rather, we are dealing with people who want to open up but then choose to defy and even destroy those sources of the Good that call them out of their hiding places.

Kierkegaard notes that “a legend has already represented [Mephistopheles] correctly. It relates that the devil for 3,000 years sat and speculated on how to destroy man—and finally he discovered it. Here the emphasis is on the 3,000 years, and the idea that this brings forth is precisely that of the brooding, inclosing reserve of the demonic” (131). He then connects the shutupness of inclosing reserve to the contentless and boring: “The prodigious span of time evokes the notion of the dreadful emptiness and contentlessness of evil” and “the quietness that comes to mind when one sees a man who looks as if he were long since dead and buried” (133).

Franz von Stuck, Lucifer (1890)

And what was the Devil’s way to destroy man? Perhaps, as Roger Scruton points out in his book Modern Philosophy (Penguin, 1994), to convince us that we are all alone in the world: “Religion is the affirmation of the first-person plural [i.e., we]. It tells us that, actually or possibly, we are members of something greater than ourselves, which is the source of consolation and continuity. Nor do you have to believe in the devil to accept the corollary: that communities may dissolve under the stress of disaffection, and that the force of dissolution can become active and willful in the manner of a god. The devil has one message, which is that there is no first-person plural. We are alone in the world, and the self is all that we can guarantee against it. All institutions and communities, all culture and law, are objects of sublime mockery: absurd in themselves, and the course of absurdity in their adherents. By promising to ‘liberate’ the self, the devil establishes a world where nothing but the self exists. This is the final triumph of the demon” (480). Demonic people, too, are out to mock, corrupt, and even destroy the first-person plural in order to convince themselves and others that the fellowship promised by the Good is a sham. Like Mephistopheles, who declares in Goethe’s Faust II (1338-1340) “Ich bin der Geist, der stets verneint” (I am the spirit that forever negates), demonic people are primarily negators rather than creators.

For example, in his book Two Ages (Princeton, 2009), Kierkegaard discusses “chatter,” or empty talk, which provides a doppelgänger—an evil double perhaps—of real conversation that can negate sincere and meaningful connections with others. He notes that talkativeness, despite its mania which “chatters about anything and everything and continues incessantly”, can be painfully boring precisely because its content is so superficial (99). It is precisely this superficiality that enables one to be mute while speaking. But we shouldn’t think this superficiality is inconsequential. Indeed, one form of chatter, gossip, can be evil. In Works of Love (Harper Row, 1962) Kierkegaard observes: “The evil element in the world is still, as I have always said, the crowd — and small-talk. Nothing is as demoralizing as gossiping small talk.” At times this gossiping takes on a “raging, demonic passion in a man, almost on a terrifying scale.”

Thomas Sully, Gossip

This passion to gossip is in contrast to love which, rather than multiplying and exaggerating people’s sins, “hides the multiplicity of sins, for what it cannot avoid seeing or hearing, it hides in silence, in a mitigating explanation, and in forgiveness” (270). Love enhances the freedom of others and helps them transcend their past and move into a better future through forgiveness and promising. Gossiping thwarts such freedom enhancement and makes people more beholden to their past or, in some cases, beholden to a past that they did not create but is created by the gossip itself. In doing so, it helps transform humans into unlovable beings. Clearly the demonic person can anxiously resort to such chatter in order to negate potentially loving relations with others in order to remain alone. So we have shutupness maintained via the contentless.

Another example arises in part one of Kierkegaard’s book Stages on Life’s Way (In Vino Veritas) through the troubling words of a demonic “fashion designer” who seeks to reduce all vestiges of taste, beauty, and virtue to crassness, vanity, and silliness. The designer in his boutique, like the Devil in hell with his legion of trained minions, snares virtuous women, sacrifices the humble content of their characters, and sends them into the world of fashion. This world facilitates a fall from grace in which a desire for superficial sameness replaces the desire to be profound individual. Thoughtful humans are miraculously transformed into dolls that, despite being objectified, manipulated, and mocked, feel no dismay in their blissful world. This is a world where the content of the self gradually empties into lunacy. Such an emptying of character can serve the demonic person well: who would want to forge a relationship with such a woman? Thus removing the virtuous content of others through temptation can remove the threat of a meaningful relationship that would offer various aspects of the Good such as love, redemption, salvation, and so on (here we should also think of the many ways women are perceived to be sluts as a means to neutralize the threat of a real relationship). Again, we have shutupness via the contentless (for more on the demonic fashion designer, go here).

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897)

These examples of chatter and fashion should not lead us to overlook even more sinister dimensions of the contentless/boring. Consider this passage from psychologist R.D. Laing’s book The Divided Self (Penguin, 1969):

“If the patient contrasts his own inner emptiness, worthlessness, coldness, desolation, dryness, with the abundance, worth, warmth, companionship that he may yet believe to be elsewhere (a belief which often grows to fantastically idealized proportions, uncorrected as it is by any direct experience), there is evoked a welter of conflicting emotions, from the desperate longing and yearning for what others have and he lacks, to frantic envy and hatred of all that is theirs and not his, or a desire to destroy all the goodness, freshness, and richness in the world” (91).

Here we can think of the many ways defiant people have attacked people, things, and places that signified the Good. Schools, sacred places of worship, successful people, events expressing solidarity, and even beautiful works of art and landscapes have been mocked, desecrated, and even destroyed in order to escape the anxiety they cause. In his book The Face of God (Continuum, 2012), Roger Scruton mentions an example that may make this dynamic clear: “The monk who burned down the famous temple of the Golden Pavilion at Kyoto — the greatest treasure of Japanese architecture — said that he set fire to it because it was so beautiful, and its beauty was a judgment against himself. Surely an inter-personal response if ever there was one” (133).

Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺) or The Golden Pavilion

The monk, Hayashi Yoken, claimed that his hatred of all beauty motivated him to perform the deed. Given the foregoing, we can say this: rather than open himself to the splendor of the Pavilion in order to become more beautiful himself, rather than see the work as an ideal to live up to, his anxiety in the face of the Good led him to burn it down so there was nothing to deal with at all. Again, we see the same strategy: this act of destruction was undertaken in order to stay enclosed within himself. Of course, we should expect, given the impossibility of complete closure we have considered above, that the monk would not rest easy with his decision. And so it was: he tried, unsuccessfully, to kill himself after the deed. This leads us to our next section.

Kinkaku-ji burning on July 2, 1950

The Self-Defeating Aspects of The Contentless

Meaning is relational: we find meaning in how we relate to things, how things relate to one another, how we relate to other humans in mutual respect and recognition, etc. Demonic people seek to drain the world of things and people that have the potential for relational meaning and, in doing so, end up living in a world to which they can’t really relate: they live in a world that is more and more meaningless. Of course this is what they want: they want to be alone and unrelated to everything but themselves. But without meaningful relationships there is no vitality, no passion, no growth, and no development of self; and so demons, like vampires, need to stay in contact with the living world of meaning to suck some Good content from it. This of course does nothing to assuage their anxiety since they remain both attracted to, and repelled by, meaning. And, since their meaning becomes the destruction of meaning, they are in a self-defeating position. In the end, the demonic end up more and more like addicts beholden to a world of human recognition without being able to enter into it. Far from destroying meaning, they become parasitic upon it.

The Inscrutability of the Contentless

One troubling implication of this view is that the more successful a demonic person is in pursuing contentlessness the less content can be known about them. But this ignorance isn’t simply because they are so well hidden. Rather it is because their inner life is so impoverished that there isn’t really much to be discovered. Indeed, Kierkegaard notes that those who seek to unravel the most intense forms of evil may end up with an x: “Let the inclosing reserve be x and its content x, denoting the most terrible, the most insignificant, the horrible, whose presence in life few probably even dream about, but also the trifles to which no one pays attention” (126). In his book On Human Nature (Princeton, 2017) Roger Scruton makes some comments about Iago that illuminate this notion of evil as an x: “Through his words and deeds Iago prompts the stunned recognition that he really means to destroy Othello, that there is no sufficient motive apart from the desire to do this terrible thing, and that there is no plea or reasoning that could deflect him from his path. After all, Iago seeks to destroy Othello by causing Othello to destroy Desdemona, who has done Iago no wrong. It is the incomprehensible, as it were noumenal, nature of Iago’s motive that enables him so effectively to conceal it. Peering into Iago’s soul we find a void, a nothingness; like Mephistopheles, he is a great negation, a soul composed of antispirit, as a body might be composed of antimatter” (137).

Iago tormenting Othello

And Terry Eagleton, in his book On Evil (Yale, 2010), makes an interesting connection connection between the contentless/boring and the Nazi Adolf Eichmann who, according to Hannah Arendt, was banal rather than demonic: “Traditionally, evil is seen not as sexy but as mind-numbingly monotonous. Kierkegaard speaks of the demonic in The Concept of Anxiety as “the contentless, the boring.” Like some modernist art, it is all form and no substance. Hannah Arendt, writing of the petit-bourgeois banality of Adolf Eichmann, sees him as having neither depth nor any demonic dimension. But what if this depthlessness is exactly what the demonic is like? What if it is more like a minor official than a flamboyant tyrant? Evil is boring because it is lifeless. Its seductive allure is purely superficial…Evil is a transitional state of being—a domain wedged between life and death, which is why we associate it with ghosts, mummies, and vampires. Anything which is neither quite dead nor quite alive can become an image of it. It is boring because it keeps doing the same dreary thing, trapped as it is between life and death.” (123-124)

The Sudden

The sudden is shutupness from a temporal point of view. Communication is about meaning unfolding over time and this unfolding presupposes continuity. One thing comes after another in some ordered way so that meaning can accumulate and reach a consummation that brings together what went before it. For example, we see how a story comes to a dramatic end, how an argument reaches a conclusion, or how a melody reaches its final note. In each of these cases the final step is not just a step or a termination; it is a fulfillment or consummation of some sort that is organically connected to what precedes it. But the sudden is a negation of continuity: “At one moment it is there, in the next moment it is gone, and no sooner is it gone than it is there again, wholly and completely. It cannot be incorporated or worked into any continuity, but whatever expresses itself in this manner is precisely the sudden” (130). According to Kierkegaard, a self is integrated when its choices and actions establish a thread of continuity from the past into the future. The sudden disrupts this integration since “the sudden is a complete abstraction from continuity, from the past and the future” (132). Kierkegaard gives us a helpful illustration from ballet that again invokes Mephistopheles:

“Without being the sudden as such, the mimical may express the sudden. In this respect the ballet master, Bournonville, deserves great credit for his representation of Mephistopheles. The horror that seizes one upon seeing Mephistopheles leap in through the window and remain stationary in the position of a leap! This spring in the leap, reminding one of the leap of the bird of prey and of the wild beast, which doubly terrify because they commonly leap from a completely motionless position, has an infinite effect. Therefore Mephistopheles must walk as little as possible, because walking itself is a kind of transition to the leap and involves a presentiment of the possibility of the leap. The first appearance of Mephistopheles in the ballet Faust is therefore not a theatrical coup, but a very profound thought” (131-132).

Music is often a helpful way to illustrate the sudden since the sudden is a temporal phenomenon and music unfolds in time. Typically demonic music will, like the disintegrated unfolding of a demonic life, violate continuity and there will be a sense that things are happening in a lawless manner. It will not seem like musical possibilities are organically emerging from past musical events. Indeed, it may seem at times that the piece can end anywhere; that there is no way to make a mistake; and that the so-called ending is not a consummation of what went before but rather just an end point. The more we say a piece can suddenly end anywhere the more we seem to miss the whole; and the more we miss the whole the more the work fails to be an analogue of a unified subject over time. It is disembodied and lacks the past-present-future existential context of an integrated subject. And in doing so it undermines our experience of being addressed by a subject who is meaningfully communicating to us. The great Christian composer Franz Liszt (1811-1886) composed many works with explicit or implicit demonic elements in order to explore the nature of evil and, by contrast, the Good. His Mephisto Polka, Mephisto Waltz (1-4), Sonata in B Minor, Reminiscences de Robert le Diable—Valse Infernale, Gnomenreigen, Reminiscences de Don Juan (after Mozart), Waltzes from Gounod’s Faust, The Night Procession, Dante Sonata, Dante Symphony, Faust Symphony, Bagatelle Without Tonality, Mazeppa, Totentanz, Unsrern!—Sinistre, Wilde Jagd, and Erlkonig are all rich with insights into the demonic. Other classical or operatic works that have demonic elements include Mozart, Don Giovanni; Carl Maria von Weber, Der Freischutz; Franz Schubert, Der Doppelganger; Richard Wagner, Faust Overture; Hector Beriloz, The Damnation of Faust; Charles Gounod, Faust; Jacques Offenbach, Orpheus in the Underworld and Tales of Hoffman; Ravel, Gaspard De La Nuit (Part III, Scarbo); Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring; George Crumb, Black Angels; Philip Glass, Dracula; and John Zorn, Goetia. These works offer us ways to aesthetically understand the abstract points Kierkegaard is making (go here for my post on demonic music for more details).

Franz Liszt

It should be noted that Kierkegaard claims the sudden, in violating continuity, is not a natural phenomenon that functions in accordance with the continuity established by the laws of nature and cause and effect. Rather, it must, unlike the many scientific attempts to grasp evil today, be understood with reference to the supernatural soul and its incoherent efforts to freely negate the freedom of the Good. Kierkegaard argues for this claim as follows:

“If the demonic were something somatic, it could never be the sudden. When a fever or the insanity etc, recurs, a law is finally discovered, and this law annuls the sudden to a certain degree. But the sudden knows no law. It does not belong among natural phenomena but is a psychical phenomenon—it is an expression of unfreedom” (130).

If Kierkegaard is right, then we should expect scientific efforts to understand evil without freedom and the soul – the “noumenal” aspects to which Roger Scruton referred when describing Iago – to fall short of a comprehensive explanation of demonic behavior. In any case, Kierkegaard’s analysis of the sudden should remind us of statements people say in the face of evil such as “the attack came out of nowhere”, “where the hell did that cruel comment come from?”, “no one could have seen that coming”, “it was like he was suddenly a different person”, and so on.

The Self-Defeating Aspects of The Sudden

A demonic person seeks to be isolated from others and would, ideally, do without others. All the selfishness associated with evil and the devil is here given philosophical expression: the demonic person wants to be alone and thus discontinuous with others since “freedom is always communicating” and “communication is in turn the expression for continuity….” (124, 129). But if he defies continuity then he risks becoming afflicted with the sudden himself: his own personal identity, his own continuity from the past into the future, will be compromised. Kierkegaard likens this state to the “dizziness a spinning top must have, which constantly revolves upon its own pivot” and notes that the “monotonous sameness” of this state can “drive the individuality to complete insanity” (130). In part two of his book Either/Or, Kierkegaard has his character Judge William offer a warning to a young seducer by the name Johannes: remaining hidden from the Good will lead to involuntary manifestations of a disintegrated self. This warning captures the self-defeating aspect of the sudden:

“Are you not aware that there comes a midnight hour when everyone must unmask; do you believe that life will always allow itself to be trifled with; do you believe that one can sneak away just before midnight in order to avoid it? Or are you not dismayed by it? I have seen people in life who have deceived others for such a long time that eventually they are unable to show their true nature. I have seen people who have played hide-and-seek so long that at last in a kind of lunacy they force their secret thoughts on others just as loathsomely as they proudly had concealed them from them earlier. Or can you think of anything more appalling than having it all end with the disintegration of your essence into a multiplicity? So that you actually become several, just like that unhappy demoniac became legion, and thus you would have lost what is the most inward and holy in a human being, the binding power of the personality?”

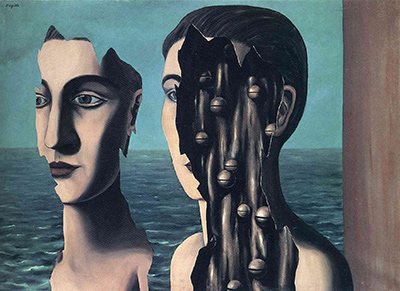

Rene Magritte, The Double Secret (1927)

Thus, in seeking to avoid continuity with others, demonic people become discontinuous: they begin to lose the very self they think their discontinuous isolation will liberate.

The Inscrutability of The Sudden

Like the above two aspects of the demonic, this violation of continuity has a disturbing implication for our understanding: the more demonic something is the less we will be able to understand it. After all, understanding presupposes continuity insofar as we seek to grasp how some past conditions gave rise to some event or might give rise to some future event. Such inquiries will presuppose the continuity of laws of nature. But the sudden is a rupture with natural continuity and therefore we should expect to have our search for continuous understanding thwarted to some extent. Therefore Eagleton puts it well in On Evil when he writes, “The less sense it makes, the more evil it is” (3).

Why are there Demons?

Why would anyone be so anxious about the good that he seeks to defy it? Why would anyone want to threaten their own freedom and the freedom of others? Why would anyone, when faced with possibilities of salvation, communication, and love say, as the demons in the Bible say to Jesus, What have I to do with you? (cf. Mark 5:17; also Matthew 8:28-34, Luke 8:26-39). Kierkegaard’s answer is that there is something in each of us that does not want the freedom of the Good. In a draft to his Concept of Anxiety, he writes: “Perhaps this may seem strange talk to some people, for who does not want to be free?” (203). But, as we briefly saw above with our analysis of the sudden, Kierkegaard thinks being a free self requires two things that cause anxiety for us: (1) we must face future possibilities for free choice and (2) we must face past necessities that flow from past choices and serve as the foundation for new ones. Obviously facing choices about our future can be overwhelming and facing our past can bring guilt, remorse, regret, and so on. As a result, people try to avoid, rather than integrate, possibilities and/or necessities to escape the burdens of freedom. But demonic people engage in a very specific pattern of this escape. Once we see this pattern many perplexities disappear and a vast array of perplexing and disturbing human behavior can be explained.

In The Sickness Unto Death (Penguin, 1989) Kierkegaard notes that the demonic begins when a person “wants to begin a little earlier than other people, not at and with the beginning, but ‘in the beginning’; he does not want to don his own self, does not want to see his task in his given self, he wants, by virtue of being the infinite form, to construct it himself” (99). The demonic individual seeks to be his own ground or a causa sui (cause of itself) by living in a limitless world of possibility alone. But attempts at self-creation, far from protecting the self from necessity, are incoherent and threaten to dissolve the self which requires the stability of necessity as much as it requires the instability of possibility. Indeed, “it is easy on closer examination to see that this absolute ruler is a king without a country, that really he rules over nothing; his position, his kingdom, his sovereignty, are subject to the dialectic that rebellion is legitimate at any moment. Ultimately it is arbitrarily based on the self itself” (100). R.D. Laing again provides a helpful description of this dialectic in The Divided Self (Penguin, 1989):

“The self, as long as it is ‘uncommitted to the objective element’, is free to dream and imagine anything. Without reference to the objective element it can be all things to itself – it has unconditioned freedom, power, creativity. But its freedom and its omnipotence are exercised in a vacuum and its creativity is only the capacity to produce phantoms” (89).

Thus it is not surprising that sooner or later the demonic person’s kingdom encounters some necessity that can’t be incorporated—a “thorn in the flesh” as Kierkegaard puts it—which, “in a Promethean way”, nails the “infinite self” to a finite restriction (101-102). Kierkegaard makes this point with reference to Macbeth whose ambition for power gets a reality check after he commits murder: “And yet despair over sin is conscious precisely of its own emptiness, of its having nothing whatever to live on, not even a self-image. The line Shakespeare gives to Macbeth (Act II, Scene 3) is a master-stroke of psychology: ‘For from this instant [having murdered the king and now despairing over his sin] there’s nothing serious in mortality: All is but toys: renown and grace is dead’” (143).

Henry Fuseli, Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers (1810–1812)

At this point something strange happens: the demonic person chooses to identify with the thorn that limits him, that is, he moves from escaping into possibility to escaping into necessity. Rather than try to integrate necessity together with possibility in order to face freedom, he substitutes one form of disintegration with another. Kierkegaard explains:

“It usually begins like this: A self which in despair wants to be himself, suffers some kind of pain which cannot be removed or separated from his concrete self. He then heaps upon this torment all his passion, which then becomes a demonic rage. If it should now happen that God in heaven and all the angels were to offer to help him to be rid of this torment—no, he does not want that, now it is too late. Once he would gladly have given everything to be rid of this agony, but he was kept waiting, and now all that’s past; he prefers to rage against everything and be the one whom the whole world, all existence, has wronged, the one for whom it is especially important to ensure that he has his agony on hand, so that no one will take it from him—for then he would not be able to convince others and himself that he is right. This finally fixes itself so firmly in his head that he becomes frightened of eternity for a rather strange reason: he is afraid in case it should take away from him what, from a demonic viewpoint, gives him infinite superiority over other people, what, from the demonic viewpoint, is his right to be who he is. Himself is what he wants to be. He began with the infinite abstraction of the self, and now has finally become so concrete that it would be impossible to become eternal in that sense, and yet he wants in despair to be himself. Ah! Demonic madness; he rages most of all at the thought that eternity could get it into his head to take his misery away from him.” (103)

The demonic person makes himself into the evidence needed to prove that existence is no good: “Rebelling against all existence, it thinks it has acquired evidence against existence, against its goodness” (105). Indeed, some demonic individuals will identify with their agony to challenge God: “No, I will not be erased, I will stand as a witness against you, a witness to the fact that you are a second-rate author” (105). So the demonic person essentially says: “If I can’t have it all then I will make myself and others as miserable as possible! In doing so I will prove the world is actually a miserable world not worth having in the first place.” This would also apply to individual things as well: if x can’t be controlled then x will be shown to be worthless.

So we see that demonic people defy the Good in order to try and escape from the anxieties and burdens of freedom that require us to forge an ongoing relationship between necessity and possibility over time. At first, demonic people escape into a dream of endless possibility and omnipotence. But they are quickly awakened from this dream by the necessities of the world and, upon awakening, go to the opposite extreme: they seek to embed themselves in necessity where they sulk, plot, and eventually attempt to neutralize the redemptive possibilities of the Good.

What can we do about the Demonic?

It is far easier to discuss the nature of demonic evil and how it comes about then to figure out what we can do about it. However, Kierkegaard offers some insights that can help us. I will first discuss one suggestion he makes about how to deal with someone who is truly demonic. I will then discuss what he prescribes for those of us who are not demonic but may have a tendency to be so on some level.

Silence and the Eye

As we have seen, part of the problem of dealing with demonic evil is that it is hidden. We did see how we can obtain hints of what is inclosed through involuntary disclosures. But typically these disclosures do not give us enough information — information we need in order to really understand, predict, and avoid evil. So is there any way we can gain more insight into the closed world of the demonic? It turns out there is. In a story in his book Stages on Life’s Way (Princeton) Kierkegaard writes: “Wrapped in oilcloth provided with many seals lay a box made of palisander wood. The box was locked, and when I forced it open the key was inside: inclosing reserve is always turned inward in that way” (189).

Joseph Cornell, Hôtel de la Clef d’Or [hotel of the gold key] (1962)

This passage shows us that the demonic person with inclosing reserve has locked himself away: the key to the silence of evil is inside. It doesn’t exist somewhere outside the person in the form of some lost good, deed, family dynamic, societal influence, etc. The outside phenomena might be occasions that influenced the move to shutupness and can, upon occasion, generate enough anxiety to invoke an involuntary disclosure. But according to this account, real openness can only come about if the evil person opens himself.

Now, in the above passage we saw that the box, which can represent a demonic soul, was opened by force. But to use force on someone to reveal their secrets is, in many cases at least, immoral. Luckily, Kierkegaard offers us another method in chapter four of The Concept of Anxiety. Consider these remarkable passages:

“An obdurate criminal will not make a confession (the demonic lies precisely in this, that he will not communicate with the good by suffering the punishment). There is a rarely used method that can be applied against such a person, namely, silence and the power of the eye. If an inquisitor has the required physical strength and the spiritual elasticity to endure without moving a muscle, to endure even for sixteen hours, he will succeed, and the confession will burst forth involuntarily. A man with a bad conscience cannot endure silence. If placed in solitary confinement he becomes apathetic. But this silence while the judge is present, while the clerks are ready to inscribe everything into the protocol, this silence is the most penetrating and acute questioning. It is the most frightful torture and yet permissible. However, this is not as easy to accomplish as one might suppose. The only thing that can constrain inclosing reserve to speak is either a higher demon (for every devil has his day), or the good, which is absolutely able to keep silent, and if any cunning tries to embarrass it by the examination of silence, the inquisitor himself will be brought to shame, and it will turn out that finally he becomes afraid of himself and must break the silence” (125).

Gerhard von Kügelgen, Portrait of Caspar David Friedrich (c. 1810–1820)

So we see that silence and the eye, administered by someone who is good and has the prerequisite spiritual and physical strength, may offer a method which forces the demonic individual to open himself up from the inside. The key, rather than being sought after outside the person, is waiting inside the person in silence. Perhaps it is no surprise then that it can only be opened with the help of silence. Of course, we may find, as we have seen with reference to the contentless and the sudden, that what we discover inside is too impoverished and/or incoherent to be of much use. But if we arrive in time there may be hope of obtaining important information and helping the person turn toward the Good before he harms others and himself.

Anxiety, Faith, and Being Open to the Good

The demonic is, as we have seen, closing oneself and others off to the Good. We have also seen how opening up to the Good can be difficult. But Kierkegaard’s analysis shows us that, to be self at all, we must be receptive to what is transcendent to ourselves whether other humans, beauty, truth, God, and so on. Kierkegaard was a passionate Christian who believed we can only actualize real integrated selfhood by acknowledging God as the standard of our development and the sustaining force of our freedom. But his basic overall vision can be embraced by non-theists as well. I think David J. Kangas describes this vision well in his book Kierkegaard’s Instant: On Beginnings (Indiana University Press, 2007):

“True freedom is not to be found in self-positing, but in the receptive turn toward what remains transcendent. Freedom is not positing but receptivity, a becoming open to what interrupts self-positing and ungrounds the self. That is the decisive turn: the Good interrupts. Hence, strictly speaking, the good cannot be willed; or rather, it can be willed only where to will has become identical with to suffer, where willing has become a letting happen. To let happen, to turn toward, to welcome: these are the gestures of the self where it is thought according to its freedom, which is always communicating.” (180)

Of course being open, suffering, communicating, and being existentially interrupted by something larger than ourselves can be overwhelming and we, as David Roberts points out in his Kierkegaard’s Analysis of Radical Evil (Continuum, 2006), “move from setting our designs upon the beautiful and the Good, and put our eyes only on what we have done, and on those aspects of existence we can control” (150). This effort to bring the world into the orbit of what we can control is a function of our selfishness, our pride, and, ultimately, our cowardice. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Book IV of his romantic classic Emile, tells us that

‘the good man orders himself in relation to the whole, and the wicked man orders the whole in relation to himself. The latter makes himself the center of all things, the former measures his radius and keeps to the circumference. Then he is ordered in relation to the common center, which is God, and in relation to all the concentric circles, which are the creatures.”

John Martin, Satan Presiding at the Infernal Council (c.1823–1827)

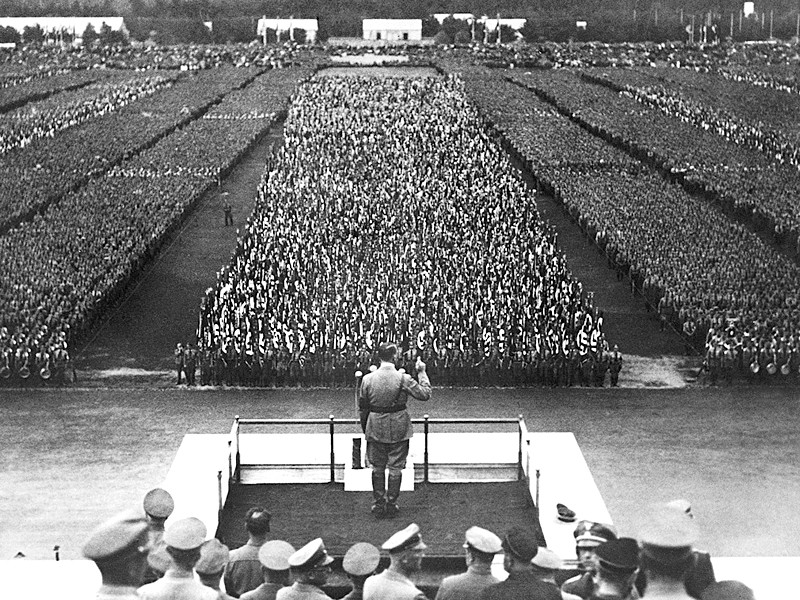

Nazi Nuremberg Rally

The demonic person seeks to make himself into the whole rather than finding his place in the whole and facing all the limitations, dependencies, and uncertainties such a place implies. Indeed, as Agnes Heller points out in Immortal Comedy (Lexington, 2005), “daemonic evil is “totalitarian” and treats others as would any totalitarian despot” (67). In her study of Nazi Germany The Origins of Totalitarianism (second edition, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), Hannah Arendt tells us how a such a despot treats people: “Total domination, which strives to organize the infinite plurality and differentiations of human beings as if all of humanity were just one individual is possible only if each and every person can be reduced to a never-changing identity of reactions, so that each of these bundles of reaction can be exchanged at random for any other” (438). Now, it might seem as if this demonic agenda to dominate doesn’t apply to most people. But Kierkegaard notes “that there are traces of it [the demonic] in every man, as surely as every man is a sinner” (122). Assuming he is right, how can we reduce these traces that can lead us to, in some form or another, defy the Good?

Kierkegaard suggests we see anxiety as something which, rather than precipitating closure and doing us harm, can help us by revealing all our finite modes of control to be deceptive. In the conclusion to The Concept of Anxiety we read:

“Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way, has learned the ultimate… Anxiety is freedom’s possibility, and only such anxiety is through faith absolutely educative, because it consumes all finite ends and discovers all their deceptiveness. And no Grand Inquisitor has such dreadful torments in readiness as anxiety has, and no secret agent knows as cunningly as anxiety to attack his suspect in his weakest moment or to make alluring the trap in which he will be caught, and no discerning judge understands how to interrogate and examine the accused as does anxiety, which never lets the accused escape, neither through amusement, nor by noise, not during work, neither by day or night.” (155)

James Sant, Courage, Anxiety and Despair (circa 1850)

The terrors of anxiety can reveal to us our limits and the deceptions we use to hide them. And it is precisely this revelation that allows for faith. Indeed, “With the help of faith, anxiety brings up the individuality to rest in providence” (161). So we see that anxiety, the very thing which can lead to the demonic, is now revealed as a way to liberate oneself from the demonic.

Kierkegaard’s vision of theistic faith may not be embraced by everyone. But his vision of having faith in order to remain open to manifestations of the Good — communication, love, forgiveness, redemption, hope, salvation, friendship, solidarity, and so on — is, I think, wise advice. To be sure, we can all improve, learn, and seek out ways to empower ourselves and others to face existential anxiety in ways that prevent the demonic. Certainly a good education, a strong sense of self-worth, encouragement of one’s abilities by a loving family and supportive community, an ability to see that we can learn and grow stronger by encounters with people who think and act differently, and the capacity to intelligently and experimentally face change are common conditions of empowerment. But how can these conditions become a common possession throughout society? What economic, psychological, sociological, religious, legal, political, and physiological aspects are involved in both the enhancement and prevention of these conditions? What can each of us do to move positive development along? There are many practical answers to these questions that offer us guides for action. But I think Kierkegaard’s point is that there will always be those anxiety-inducing factors over which we have little or no control. These factors require us to have faith in the Good as we move forward in our efforts. And this faith can help us keep at bay those cynical, pessimistic, and embittered traces of the demonic which tempt us to turn away from the Good and thus from ourselves and others.

Summary of Kierkegaard’s Account of the Demonic

The demonic person is anxious (both attracted and repelled) about the Good and its promises of freedom, unification, love, solidarity, redemption, salvation, etc. This anxiety leads to a self-conscious defiance of the Good in order to escape the choices, responsibilities, and regrets freedom entails. The primary mode of defiance is shutupness or voluntary isolation. However, to maintain isolation demonic people will pursue contentlessness by destroying any meaningful content that threatens to draw them out: they will negate the continuity, communication, meaning, and life of the Good leaving behind isolation, muteness, meaninglessness, and even death. This freely chosen and destructive defiance of the Good is evil. Since integrated selfhood presupposes meaningful communication and relations with others, the more demonic people’s defiance succeeds—the more they are isolated and shun modes of the Good—the more they are marked by the sudden and begin to disintegrate. In many cases, the process of disintegration results in unfree or involuntary disclosures of what was hidden. But we must accept that the understanding such disclosures bring will be limited insofar as the evil of the demonic is profoundly hidden, loses content as its negation develops, and violates the very continuity any act of understanding presupposes. Unfortunately, demonic evil will, in many cases, remain inscrutable. But silence and the power of the eye can be used as a means to obtain much needed information. Finally, demonic evil can best be prevented by helping people develop the capacity to remain open to manifestations of the Good and avoid seeking to control it. One powerful way this openness can be facilitated is by allowing anxiety to show us our limitations in order to make room for faith which is a necessary condition for the possibility of action that can enhance the freedom of the Good both individually and collectively.

© Dwight Goodyear 2017

Soren Kierkegaard

For my series on Kierkegaard’s philosophy that can place much of the above in a larger context, go here.

For my post on demonic music that uses Kierkegaard’s theory, go here.

For my posts on Hannah Arendt’s theories of evil, go here.

For my posts on Shakespeare’s Richard III and various forms of evil, go here.

For a post that contrasts natural evil and moral evil, go here.

For a three-part series on the privation theory of evil, go here.

For a post that explores utilitarianism and evil, go here.

For my five-part series on solitude which explores some of the above themes, go here.

aye. nice text.

somebody posted this on 9gag. (was it you?)

i read some passages.

i would define it much simpler:

some people have the possibility to understand, comprehend, etc

and some just don’t. hence they choose a simpler path and take what they can get. by force, or compensating with status symbol products. which utimativly leads to aggressiveness and a kind of zombiefication.

just an ungraceful way of dying.

and they at least create a surrounding in which sensitve people can’t possible exist.

so i kind of agree.

but what’s the solution for the problem in your opinion?

Hi Valentin

Thanks for your comment. I had no idea my post was on 9gag – I certainly didn’t post it. An odd place for a long essay on Kierkegaard I suppose. Anyway, I agree with you that one explanation for how people can become aggressive and, as you say, “create a surrounding in which sensitive people can’t possibly exist”, is that they have limits of comprehension that lead them to choose a “simpler path.” Your account might be simpler than Kierkegaard’s – I’m not sure. But we aren’t after simplicity here. We are trying to get a grasp of one particular form of human evil and its motives that, I think, needs to be understood and is, as Kierkegaard says, far more common than people suppose. Kierkegaard’s very specific explanation is that demonic people have anxiety about the good – attracted and repelled by the good – and, to escape this anxiety, they end up defying and even destroying the good that they admire. This willing defiance and destruction of the good that is known to be good is, I think, a unique form of evil that is consistent with traditional visions of the devil. People who have limitations, choose an expedient route (through force, aggression, crime, bullying, etc.), and end up hurting others need not be demonic in their motivation: they are more likely moved by their ignorance, cowardice, greed, and so on to do the things they do. We can, in the end, refer to extreme cases of what you describe as evil since I think it is wise not to argue that there is ONE form of evil. There can be a set of forms with family resemblances that bring understanding without resorting to one shared essence. But one form, the demonic, has its own twisted logic that I think resists being reduced to the more common forms of human viciousness. Now, you ask: what do I think we should do about demonic evil? Well, I lay out some suggestions in the post in the final section: “What Can We Do About the Demonic?” So check that out.

Thanks for reading.

the monk that burned down the shrine because its beauty became repulsive seems to be oxymoronic. evil detests beauty (the good) because its own inherent flaw is revealed. i recall frankenstein, the monster, chasing after its creator shouting “you made me!” the good did not make man the monster. the good made man upright. seems evil gravitates to if i can’t the author, then no one else can be. there is no sense that evil can ever justify its being.

Hi Rickey

I’m not sure exactly what two terms are oxymoronic. But on Kierkegaard’s account, which is based on anxiety (being both attracted and repelled by something), the demonic person is both attracted and repelled by the good, one manifestation of which is beauty. So here it is not the case that evil simply, as you say, detests beauty. It does, but it is also attracted to it (since everything is attracted to the good). This attraction calls evil out of its hiddenness and desire to be completely self-centered and independent and, in doing so, needs to be neutralized in some way (“the contentless”). If the manifestation of the good remains (the temple for example) then the demonic person would have to face judgment, grow morally, accept responsibility, drop pride, etc. Of course the good always remains! So evil, as a privation of the good, always remains ontologically dependent and the more evil it becomes, the more self-destructive it is.

If the small talk of the crowd is ‘an evil element in the world’, and I live in a society which is fairly superficial and small talk is the overwhelming means of interaction, what am I supposed to do to avoid being demonic? If I retreat from small talk I am demonic, because I then fall into the trap of ‘shut-upness’ and isolation. Equally evil. (I do not agree with the harsh assessment of small talk and it makes me wonder about the entire tendency of K. to find evil in harmless social interactions and ordinary means of coping). Finally, can you help me understand the crucial difference between the kind of ‘profound stillness’ that is discussed favorably in post 4, versus incriminating solipsism and reserve (labelled demonic by Kierkegaard) addressed here? Thank you. I very much enjoyed your post on Agnes Heller’s world and will keep reading.

Thanks for your perceptive comments and thanks for reading Sharon. To answer your first question we can focus on intent: if one’s intent is to avoid the gossip and demoralizing small talk then one is admirably resisting the demonic and its trait of removing meaningful content, communication, love, and so on from the world. Kierkegaard explores this withdrawal towards positive spiritual development in Fear and Trembling when he discusses the silence of the knight of faith. He also discusses it in Two Ages when he speaks of people who resist the “chatter” of the “public” and “the press” as being “unrecognizable”, that is, resisting by being silently steadfast in their moral commitments. Here you can think, as Kierkegaard often does, of Socrates and how he would periodically be frozen – still and silent – as he would work out some philosophical problem. And, of course, the many religious prophets who withdraw from secular life, go into the desert, and so on to cultivate their religious awakening. But if, on the other hand, one’s intent is to be silent to undermine the good rather than pursue it then we have the demonic. So Kierkegaard explicitly draws a distinction (see part two of Stages on Life’s Way) between two types of withdrawal: one away from and one towards the good and the deepening of moral/spiritual commitment. Given all this, you can see a way to not engage in small talk and avoid being demonic (thank goodness!). Of course the real task for Kierkegaard the Christian is to figure out ways to help others become less enclosed and more connected to the good through the kinds of works that he explores in his book Works of Love.

As far as your other question is concerned, I would say that the stillness of contemplation, balance, and so on can be the means to the spiritual form of withdrawal mentioned above: one that helps us center ourselves (like so many meditation traditions do) so that we can avoid being caught up in all the noise and manipulation of the world. It can help us retain a sense of timelessness that can put our world of process in a radically new perspective. Engaging with minimalist art has always helped me do just that.

Anyway, hopefully these ideas help a bit – let me know if you have any other thoughts or questions.

Pingback:The Necessity of Invented Devils: Humanity’s Eternal Dance with Evil