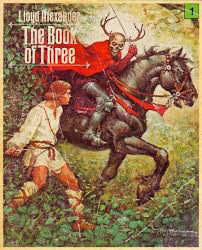

173. A Riddle about Evil from Lloyd Alexander

Lloyd Alexander

Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007) was one the greatest authors of novels for young people. His five book series Chronicles of Prydain is one of the most entertaining and profound fantasy epics of all time. Before becoming an author of over 40 books and winning many coveted awards, Alexander translated some of Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophical novels, such as Nausea and The Wall, from French into English. Sartre’s philosophy, which emphasizes freedom, choice, and authenticity, seemed to leave a powerful mark on Alexander whose stories typically portray characters facing existential decisions. Indeed, my ongoing love of existentialism can be traced back to my early love of the Prydain series which I read when I was ten. These decisions leave the reader, both young and old, with a lot of food for thought. But his writing includes many other philosophical insights about morality, politics, love, art, society, and so on.

Recently I read the series to my son, also ten, and I was amazed at the many insights I missed, or couldn’t adequately process, as a child. One insight I would like to share – really a bit of a riddle – comes up in chapter 19 of the first book in the series, The Book of Three, and has to do with evil. Consider these passages in which the wise and courageous Prince Gwydion is speaking to young Taran, the great hero to be, about the evil Horned King:

***

“He, too, realized the one thing that could destroy him.”

“What was that?” Taran asked urgently.

“She knew the Horned King’s name.”

“His name?” Taran cried in astonishment. “I never realized a name could be so powerful.”

“Yes,” Gwydion answered, “Once you have courage to look upon evil, seeing it for what it is and naming it by its true nature, it is powerless against you, and you can destroy it.”

***

What is Gwydion talking about here? How can we make sense of this? If you have any suggestions, please post them! I think one insight worth sharing is this: if evil people are, as Soren Kierkegaard pointed out, in part defined by their effort to defy the good by shutting themselves up in hidden isolation, then seeing into this isolation might indeed mark the end of evil. For an overview of this approach, see my posts on demonic evil here.

“

Came here looking for an answer to whether the translator of Sartre was the same Lloyd Alexander whose books I loved as a child. Turns out it was! Thanks, and like you I think this helps account for my own later affection for all things existential.

I terms of you question about evil, two quick thoughts. First, the tradition that if you can call something by its “true name” you will have power over it is common I think in accounts of mages and other magic-workers, and perhaps is reflected too in the story of Adam naming the animals in Eden.

Second, in a more existential vein, there’s the idea in both Sartre and Kierkegaard that we use language to hide the truth from ourselves, we take refuge in vagueness or in euphemisms in order to avoid facing the truth. SK thinks most people who call themselves Christians have no idea what they are talking about. Sartre calls this bad faith. From this perspective, even calling something “evil” might be a way to avoid confronting it while kidding ourselves that we are being brave, speaking the truth, etc.

I’m glad the post helped CJ. And thanks for your comments. I think your first suggestion about the magic-working tradition of true naming fits in well with Alexander’s mythology in the text. Your second comment is interesting and applies well to all the ways the concept and the word ‘evil’ are thrown around so carelessly in ways that generate ignorance. It is certainly consistent with the view, widely maintained by those who deny the existence of free will, that ‘evil’ is an archaic word that helps prevent us from understanding the determined neurological grounds for so-called evil actions. But if we think the word ‘evil’ has a real moral reference, then your insight leaves the mystery in place: if, according to many existentialists, language hides truth from us, then how can we make sense of Gwydion’s point that it is precisely in naming the true nature of evil that it can be destroyed? Here the naming, far from obscuring the truth of evil, seems to reveal it and, in doing so, annihilates it.