161. Some Notes on Sartre’s Existentialism

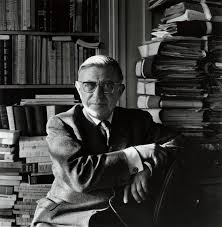

Here are some notes on Jean-Paul Sartre’s (1905-1980) existentialism that continue, on some level, to apply to the world around me more than any other set of philosophical propositions (for a more in-depth overview of the man and his many works go here).

In Being and Nothingness (1943) Sartre describes two fundamental types of beings in the world: the “in-itself” and the “for-itself.” The in-itself is what it is: it has no possibilities, no consciousness, no choice, and no sense of time. A stone is simply a stone and it has no sense of emptiness, experiences no lack, and is full. All objects fall into the category of the in-itself. The for-itself is what it is not and is not what it is. This means the for-itself can define itself by what it is not yet: a student sees herself as what she is not yet—a graduate—and acts in accordance with that projection of possibility (i.e., is what it is not). Moreover, at any moment the for-itself can say “I am not what I currently am” and move beyond present facts and circumstances by negating them (i.e., is not what it is). Sartre thinks consciousness is a power of negation, of nothingness, that allows a for-itself to freely make choices and give meaning to an otherwise meaningless world of objects.

Sartre then introduces two other terms that help clarify the dynamics of the for-itself, namely, “facticity” and “transcendence”. Facticity represents all those facts we need to face about ourselves such as acts committed, things that befall us, etc. In general, facticity is our past. To deny facticty is to remove a necessary condition for freedom. Freedom is not abstract and indifferent; it is always freedom from something to something. Transcendence represents our ability to not be reduced to our facticty. Through our power of negation we can see things differently, give new direction and meaning to past events, and imagine new possibilities. We can choose new courses of action not determined by the past. So transcendence is future-oriented. To deny our ability to transcend is also to remove a necessary condition for freedom.

Sartre argued freedom is a defining characteristic of human beings. The reality of genuine freedom in our lives means we can choose between transcendental possibilities, act, and then develop facticity from those acts for which we are responsible. Unlike many other theories of human nature (natural law theory for example) Sartre’s theory maintains we don’t have a fixed essence (rationality for example) that serves as the guiding principle for our development. Rather, he asserts, in a now famous existential slogan from his book Existentialism Is a Humanism (1946), that “existence precedes essence.” This means that while we exist our lives have a radical openness and who we essentially are will be the sum total of our actions once we are dead.

However, following Soren Kierkegaard analysis of anxiety in his book The Concept of Anxiety, he observes that humans typically try to escape freedom because of the anxiety and suffering it causes. Since freedom is germane to the human condition, this amounts to the impossible task of humans escaping their humanity. Sartre calls the impossible avoidance of freedom acting in “bad faith.” Bad faith occurs by denying our facticity and/or our transcendence. It is simply overwhelming to face all the transcendent possibilities that bubble up and threaten the so-called solid obligations, practices, and beliefs that make up one’s facticity. Indeed, existential anxiety differs from fear insofar as it is not directed toward a fearful object but towards the very notion of being able to do something else. But the trouble doesn’t stop with transcendence: for it is obviously painful to take responsibility for one’s facticity as well. We conveniently avoid guilt, forget shameful deeds, and are happy to stress the good and overlook the bad in ourselves. Taken together, this gives us a formula for an escape from freedom: bad faith occurs when we seek to run into total transcendence and deny facticity OR when we seek to reduce ourselves to our facticity and deny that we can transcend. Take note that the word ‘faith’ is here to capture our decision to move past evidence we have and embrace a freedom denying narrative. For example, a man may indeed have done terrible things in his past which make him wary about changing for the better in the future. But he then moves past that evidence in faith and chooses a narrative that defines himself as a terrible person so no change is undertaken (go here for some of Sartre’s memorable “patterns of bad faith” from Being and Nothingness and see links below for applications of Sartre’s ideas to racism). This would be opposite of the kinds of faith or confidence we often have in ourselves and others that move past certain facts and project a future with more freedom and growth.

If we are able to avoid the denials of bad faith then Sartre claims we have the opportunity to act authentically or in “good faith” which can also be put into a formula: authentic action or action in “good faith” occurs when we accept facts AND we don’t reduce ourselves to facts: we take responsibility for the past and accept that as free beings we can transcend into a new futures with new possibilities.

Authentic action, however, is very hard to realize as we have seen. Moreover, people are always trying to steal our freedom and we are seeking to steal freedom from them. We find ourselves temporarily losing our freedom when we are victims of the “look”: the gaze from the other that suddenly makes us act as they want us to or be what they think we are. Of course, we can also turn the look onto others and freeze them in our Medusa-like gaze. Whatever the case may be, we are enmeshed in a world of shifting power relations in which our efforts to be authentic are more often failures than successes.

Sartre gives an interesting account of this failure. He claims we all dream of being both a subject and an object at the same time; we wish to be free and indeterminate as a subject yet also finished and complete like an object. Moreover, we wish our lovers could be this way as well: we want them to be subjects to whom we can relate, yet we want them to be objects that we can control which won’t threaten our freedom. But if this is the case then we obviously can’t have what we want: we can never be both a for-itself (subject) and an in-itself (object) at the same time since this is contradictory and thus impossible.

Sartre discusses the self-defeating strategies of sadism and masochism to dramatically illustrate his points. He points out that the masochist wants to be an object, but tragically wants to know himself as an object. But such knowledge would imply that he be an object and a subject at the same time—a contradictory task which is impossible. Similarly, the sadist seeks to possess another’s freedom by reducing this other to a mere object. But he also wants the person so reduced to be aware of their humiliated state. This is yet another absurd attempt to make an object into a subject at the same time. Underneath both these strategies is a self-defeating desire to escape freedom. If someone can just be an object of sexual pleasure he doesn’t have to worry about transcendence, about the future, about possibilities. If someone can reduce other people to objects then he doesn’t have to be threatened by a future with that person, doesn’t have to be judged by that person, etc. The masochist wants his freedom to be possessed; the sadist wants to possess it. Given all these power relations, Sartre tended to be quite pessimistic about the prospects of two equal subjects coming into a meaningful relationship. To be sure, we are doomed to love since we are nothing ourselves and find being in the other; but in the end our failures may lead us to say, with Sartre’s character Garcin from his play No Exit (1944), that “hell is other people.”

It is important to note that Sartre thought this analysis implies that God, who needs to be a pure subject that is nonetheless complete, doesn’t exist. But this makes way for our freedom since if God did exist we would be predetermined by his plan for us: we would have an essence prior to existing and this would undermine our freedom. Thus Sartre championed atheism along with his version of existentialism (Kierkegaard’s existentialist philosophy is, by contrast, theistic).

So those are some basic notes on Sartre’s existentialism. They certainly seem to, as my late, great colleague Jim Kuehl once said, “explain everything.” After all, aren’t we endlessly denying aspects of our past in lies, fantasies, excuses, and acts of scapegoating? Aren’t we endlessly denying we can be otherwise with fatalistic narratives about how it is too late, how we simply can’t, how there is just no way? And don’t our experiences of anxiety, the look, and sadism and masochism reveal our freedom in clear and visceral ways? The more we look on ourselves and others with an honest gaze the more supporting evidence we appear to find.

Nonetheless, many questions can be asked: do we even have the radical freedom he thinks we have? Many now argue, especially in light of the results of neuroscience, against the existence of free will and so the basic premise of Sartre’s analysis may be mistaken. And even if we do have freedom, are we really capable of transcending to the extent Sartre thinks we are? Are we really in flight from freedom to the extent he thinks we are? Are things really so bleak when it comes to love? And is our freedom really incompatible with God’s existence? Moreover, it seems false that we have no nature. Don’t we find plenty of good potentials in our nature – to reason, be social, love, imagine, create, pursue justice, appreciate beauty, and so on – that can serve as an objective ground for moral guidance? Aren’t these potentials verified by science? Shouldn’t we avoid transcending them and do our best to actualize them for human flourishing? Isn’t it bad faith to do otherwise? We could also raise questions about Sartre’s lifelong commitment to socialism and the existential form of Marxism he forged in Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960) as a way to empower people to overcome the economic anxiety he thought radically delimited their transcendence. Later in his life he correctly saw that resisting oppression requires both individual freedom and institutional support. But can’t the negative aspects of capitalism that do smother people’s freedom be reduced, reformed, and even removed to make room for freedom? Wouldn’t socialist and Marxist-inspired alternatives be worse? And even if not, is Sartre’s vision of individual freedom really consistent with any system that advocates the social ownership of the means of production?

Perhaps questions like these led Sartre, who was once a 1964 Noble Prize winner (he refused to accept it) and the most famous intellectual in the world, to no longer be a household name. But, as this article in The Guardian points out, he may be more relevant now than ever since “The existential plight of humanity, our absurd lot, our moral and political responsibilities that Sartre so brilliantly identified have not gone away; rather, we have chosen the easy path of ignoring them. That is not a surprise: for Sartre, such refusal to accept what it is to be human was overwhelmingly, paradoxically, what humans do.” Surely we still face opportunities to see ourselves as determined objects – things – necessitated by forces in physics, chemistry, biology, society, politics, and so on. Perhaps, in the end, we are necessitated by such forces. But if you agree with the key idea of his existentialism – that we are far more free than we realize and can indeed transcend our facticity in many cases at least – then that you might find the above notes as a helpful means to diagnose and hopefully overcome to an extent the various attempts in yourself and others to flee this freedom in bad faith. That is, you might find them helpful as a means to reduce the cowardly sadistic and masochistic excuses, lies, scapegoating strategies, groundless fantasies, rationalizations, and hopeless narratives and be more authentic.

Go here for my critique of Sartre’s argument for freedom.

Go here for overview of Sartre’s account of racism.

Go here for my post on George Floyd and Sartre.

Go here on my post that explores Sartre’s account of sadism and masochism in the context of Kant’s moral theory.

Go here for my post on R.D. Laing’s existential psychology that features Medusa.

Go here for my posts arguing for free will.

Go here for my posts on Kierkegaard.