145. The Cognitive and Moral Worth of Halloween

A still from Ingmar Bergman’s thoughtful horror film The Hour of the Wolf

Aesthetic expressions of horror are produced and enjoyed by people all over the world. But some bemoan such horror and do their best to avoid it. Over the last few years I have spoken to quite a few students, colleagues, family members, and neighbors about their unease with Halloween imagery. Some told me they are pleased to see how little horror is present these days. And some would like to see it all eradicated! I disagreed with all them. But these encounters made me ask: Why would we support such horrific imagery? Why should we keep the horror in Halloween? Here are some suggestions that fall into the categories of (1) cognitive stimulation for understanding and (2) insights related to our moral development.

The Cognitive Value of Halloween

I think philosopher Cynthia A. Freeland, in her book The Naked and the Undead (Westview, 2000), offers one convincing justification of horror films in this passage:

“Films of uncanny horror prompt a complex cognitive and emotional response of appreciation for the worldview they represent. We may not endorse or accept their message, but we can find it worth considering and responding to….As a whole, the uncanny object, if it is an artwork like a film, can have an aesthetic power in the way it requires us to feel repulsion or dread, to “see” and reflect about the horrors it so evocatively presents. We could not think seriously about such a worldview if we did not picture it and respond to that image so thoroughly.” (239)

Do we, like Dracula, turn away from self-reflection when it comes to death and evil?

Like many good horror films, the varied imagery of Halloween can be seen as a means to contemplate a worldview that includes threats to the good, evil, repressed feelings and memories, ambiguous identity, death, injustice, abnormality, insanity, and so on. In doing so we have an opportunity to think about many elusive phenomena that, while difficult to deal with, are indeed part of our world. This would be a cognitivist or instrumental approach to Halloween, namely, one that sees it as a means to intellectual stimulation that can teach us something and help us see the world and ourselves in a more comprehensive, sensitive, and honest way. And Halloween is qualified to help us in this regard since there is, of course, an ample amount of fun which provides the distance needed to deal with the horror.

For example, we might investigate how the aesthetic category of the uncanny and see how it applies to Halloween-related material. An uncanny experience occurs when something familiar becomes unfamiliar at the same time in an unsettling way. This experience, as Sigmund Freud argued in his essay “The Uncanny” (1919), reveals a return of the repressed which can tell us something about our unconsciousness in a way different from other psychoanalytic approaches such as dream analysis, free association, parapraxes (Freudian slips), transference, and resistance to analysis. For example, Freud claims we were animists in our childhood, that is, we believed plenty of things without life were alive. We spoke to various toys and related to them as subjects. But then we grew up and learned that our beloved toys are just objects. However, in many people their animism don’t simply disappear: it is repressed in the unconscious. So, when an adult has an uncanny experience in the presence of a creepy doll or ventriloquist’s dummy (as in the film Magic), Freud would say that what is familiar—an object that is simply wood—has suddenly become unfamiliar in light of repressed beliefs about dolls being living subjects. By explaining the uncanny with reference to two levels of the mind, he is able to do justice to the fact that we experience familiarity and unfamiliarity at the same time. But he is also able to avoid contradiction since, while we experience these different perspectives at the same time, we do not do so in the same respect. In one respect, the conscious and scientific one, we see the doll as dead; in another respect, the unconscious and repressed animistic one, we experience it is alive.

Magic (1978)

Freud goes on to apply the same strategy to his other examples of the uncanny and unearths a unique form of repression for each whether an infantile complex or a primitive belief. For example, mechanical repetitions are related to a repressed death instinct with its compulsion to repeat; doppelgangers and ghosts are related to a repressed childhood denial of death which doubled the self; severed body parts and damage to our eyes are related to a repressed fear of castration; possession-like events such as epilepsy are related to a repressed belief that we are, despite our sense of freedom, determined by physical law; evil eyes and effects that correlate with our wishes are related to a repressed belief in the omnipotence of thought based on childhood narcissism; and premature burials are related to a repressed death instinct which pulls us back toward the womb or an “intra-uterine existence.” Some or all of his explanations may be wrong. But his strategy is promising and Halloween can offer plenty of opportunities to explore uncanny revelations and creatively transfigure them.

A return of the repressed can also reveal acts of social injustice, transgression, hubris, and so on: a return of the oppressed. The uncanny ghost or monster returns to reveal uncomfortable truths and call us to account. For example, John Carpenter’s classic film The Fog (1980) confronts us with an uncanny fog (it moves against the wind and has a purpose) which is the vehicle for ghosts who have returned to redress a grave injustice, one that was the means to establishing a flourishing and self-righteous community.

Blake and his men returning for justice in The Fog

The injustice in the film is based on a true act of injustice in the early 1800s in which indigenous people were massacred in the vicinity of Goleta, California. But we don’t need to know this in order to think about what acts of injustice may lie at the foundation of our communities and, perhaps, what our ignorance of such injustice does to perpetuate it. We can also think here of the many monsters which serve as cautionary symbols of environmental destruction. One of my favorites is still the eccentric and entertaining Godzilla vs. Hedorah (or “The Smog Monster”) from 1971 in which we encounter a creature that, after growing from a tadpole to a massive land and air monster by feeding off our excessive pollution, returns our selfish destruction of the earth to us in the form of toxic fumes and sludge:

These monstrous returns of the oppressed help us realize that all too often it is humans who are the real monsters.

Expressions of horror can also offer us insights into types of action and people that can teach us universal truths about the human condition. Obviously, many works of horror feature superficial depictions of character and, sadly, pop culture often ends up substituting such depictions for the rich ones offered in, for example, novels such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, Franz Kafka’s The Trial, Stephen King’s The Shining, Thomas Harris’ Silence of the Lambs, and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian to name a few. By engaging with profound works of horror we can delve into universals of human nature which less horrific material may fail to portray.

And we can gain insights by investigating musical representations for horror as well. The great Franz Liszt (1811-1886) composed many works with explicit or implicit demonic elements such as Mephisto Polka, Mephisto Waltz (1-4), Sonata in B Minor, Reminiscences de Robert le Diable—Valse Infernale, Gnomenreigen, Reminiscences de Don Juan (after Mozart), Waltzes from Gounod’s Faust, The Night Procession, Dante Sonata, Dante Symphony, Faust Symphony, Bagatelle Without Tonality, Mazeppa, Totentanz, Unsrern!—Sinistre, Wilde Jagd, and Erlkonig (for a good introduction to Liszt’s demonic works, get Earl Wild’s album Liszt: Masterpieces for Solo Piano, Vol. 2 whose second part includes a nice sample).

Franz Liszt, the Christian Master of Demonic Music!

Other classical or operatic works that have demonic elements include Mozart, Don Giovanni; Carl Maria von Weber, Der Freischutz; Franz Schubert, Der Doppelganger; Richard Wagner, Faust Overture; Hector Beriloz, The Damnation of Faust; Charles Gounod, Faust; Jacques Offenbach, Orpheus in the Underworld and Tales of Hoffman; Ravel, Gaspard De La Nuit (Part III, Scarbo); Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring; George Crumb, Black Angels; Philip Glass, Dracula; and John Zorn, Goetia. I have learned a great deal by studying such works which, in offering musical forms of disintegration and destruction, offer insights into the nature of evil and, by contrast, the nature of the good with its integration and creation.

The Moral Value of Halloween

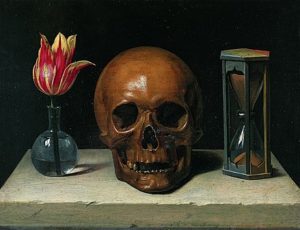

So far I have briefly discussed a few ways we might glean some cognitive stimulation from Halloween-related material. But we can also glean some moral dimensions to the holiday as well. The memento mori (remember that you have to die) tradition “is the medieval Latin theory and practice of reflection on mortality, especially as a means of considering the vanity of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits. It is related to the ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) and related literature. Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character, by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.” (Wikipedia). Memento mori art, far from coming out once a year, was integrated into people’s homes and, of course, places of worship. It served a cognitive and moral function despite its horror. For example, Philippe de Champaigne’s Vanitas (c. 1671) presents the three essentials for us to contemplate, namely, Life, Death, and Time:

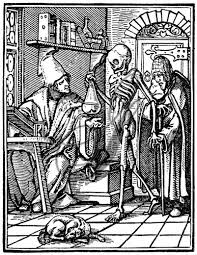

We could also consider the many depictions of the dance of death in which Death appears to take everyone away regardless of their stations in life. Hans Holbein’s (c. 1497-1543) disturbing yet funny woodcuts are excellent examples. Here is his image of Death coming to take away even the doctor who helps preserve life:

These works aren’t only instrumental to understanding something. They were the means to practicing something and becoming a better person. Cultures all around the world have different ways of remembering death and incorporating such memory into their lives. But all too often we deny death and overlook that our lives may not last another year, day, or even minute. Seeing strange images of death in the environment for a few weeks can, perhaps, put some things into perspective so we can lead more fulfilling lives and focus on what really matters. And, in some cases, they can be the means to a catharsis, a purging of certain negative and repressed emotions, which can help us restore balance to our characters.

Finally, horror can serve a moral function if we invoke something which Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), in his book Critique of Judgment, referred to as the dynamic sublime. Typically this form of the sublime occurs when we make judgments about mighty things that have the capacity to hinder, resist, and destroy our physical well-being. Kant gives some examples: “Bold, overhanging, and, as it were, threatening rocks, thunderclouds piled up the vault of heaven, borne along with flashes and peals, volcanoes in all their violence of destruction, hurricanes leaving desolation in their track, the boundless ocean rising with rebellious force, the high waterfall of some mighty river, and the like, make our power of resistance of trifling moment in comparison with their might.”

John Martin The Great Day of His Wrath (circa 1851)

In such cases we experience the might of nature and, to be sure, experience displeasure in the revelation that our physical powers, even when extended by technology, are so exceedingly small. But if we are making a judgment of the sublime we also come to realize that we are free to stand up to such overpowering might. We come to see that, while our body and personal belongings are obviously dependent on the forces of nature, our personhood exists as free and independent of these forces. This awareness of our freedom allows pleasure to follow displeasure. Thus the sublime is able to edify us as free souls even as it shows us the limits of our bodies. This is important since for Kant our capacity to act freely is what makes morality possible.

We can easily connect this account of the sublime to horror as follows: certain fictional depictions of terror offer us, on the one hand, ways for our imagination to experience absolute defeat in the presence of dark forces as far as our finite bodies are concerned and, on the other hand, this very defeat can allow us to experience our capacity to freely stand up to such might should the real occasion arise. Some horror films show us there are forces over which our natural bodies and technology have, ultimately, no control. But such pessimism can end up invoking an optimistic view concerning our lives as free moral agents. This, I think, is one of the non-sadistic ways horror brings pleasure: it can offer us an aesthetic experience of the sublime that reveals our freedom and dignity as moral agents.

Given this instrumental analysis, we see that Halloween can be a means to cognitive and moral development by helping us understand, express, transfigure, share, and have fun with our fears in a communal way. Therefore I say, against some efforts underway to the contrary:

Keep the horror in Halloween!

A creepy still from John Carpenter’s classic Halloween

For my blog series on the uncanny go here.

For my blog on Freud and the deinal of death, go here.

For my post on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” and COVID-19, go here.

For my series on Dracula here

For my more thorough account of the sublime in Kant’s philosophy go here.

For my blog on demonic music go here.

For my essay on Kierkegaard’s account of demonic evil, go here.

For more on art and its ability to give us understanding, go here.

For my post on Medusa, go here.

For my post on ugliness in art, go here.

Love your blog and its message, Dwight. Philippe de Champaigne’s still life and Holbein’s woodcuts are great references for your theme as well as visual reminders of our vulnerability. I particularly love the Mexican celebration of Day of the Dead (Nov.1st) where people laugh at death and joyously honor the passing of loved ones by laying flowers (marigolds) on their graves.

Your conclusion is perfect; keep the horror in Halloween (but also the fun)!

Great work professor Goodyear, I really liked the part which you talked about reflecting on death. It fascinating everything is born and then dies. Or does it? Reading philosophers such as Epicurus, Lucretius etc.

Keep up the good work!

Most definitely, “keep the horror in Halloween!”. I enjoyed writing about, Freud, for my psychology classes. This has sparked my interest, of “The Uncanny”. I truly want to see what stage it falls on, or if there are any to begin with. Michael Meyers standing behind the clothes-lines, still gives me the creeps! This iconic Halloween movie of the late 70’s never gets boring. I am intrigued to know, that philosophy has a theory on Halloween, very interesting. However, does Halloween celebrate death of others, or is it to glorify the goodness or means of our own lives? Good blog, and thank for the information.

I am glad you enjoyed the blog, thanks for reading. Yes, the uncanny is a fascinating topic. If we try and relate it to Freud’s stages, then I suppose, based on his examples in his essay “The Uncanny,” that it would appear from the genital stage on since young children exhibit and enjoy various behavior (animism, doubling themselves with imaginary friends, and enjoying repetition for example) that adults find uncanny. However, many children (including myself) have uncanny experiences. So I wouldn’t accept this analysis. You also ask about Halloween as a means to celebrate the death of others. Well, here we can certainly acknowledge Freud’s emphasis on the sadistic tendencies in so many humans and note that Halloween offers plenty of ways to express such tendencies in ways that are sublimated rather than neurotic. Such sublimations, through imagery, movies, role playing, fantasy, and so on, can serve as a catharsis which can (following Aristotle’s analysis of tragedy) purge negative emotions and help bring more control to the soul (a moral benefit). And it can be cognitively interesting to study sadism in creepy literature and film from a safe distance to better understand it (a cognitive benefit). Now, this is not about “celebrating” the death of others: if someone genuinely celebrates the harm of the others then that is obviously a problem and is not what most people are up to on Halloween. But I think exploring the death of others (and oneself) can be beneficial within the limits of the points just made. Such benefits need not, as you say, be about glorifying the goodness of our own lives. But if my analysis based on the sublime and remembering death makes sense, then Halloween can at least be a means to becoming a better person.