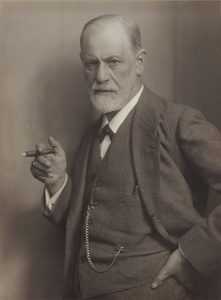

152. Freud vs. Plato

In chapter 4 of his book Civilization and its Discontents (translation by James Strachey) Freud writes:

“Before we go on to enquire from what quarter an interference might arise, this recognition of love as one of the foundations of civilization may serve as an excuse for a digression which will enable us to fill in a gap which we left in an earlier discussion. We said there that man’s discovery that sexual (genital) love afforded him the strongest experiences of satisfaction, and in fact provided him with the prototype of all happiness, must have suggested to him that he should continue to seek the satisfaction of happiness in his life along the path of sexual relations and that he should make genital erotism the central point of his life. We went on to say that in doing so he made himself dependent in a most dangerous way on a portion of the external world, namely, his chosen love-object, and exposed himself to extreme suffering if he should be rejected by that object or should lose it through unfaithfulness or death. For that reason the wise men of every age have warned us most emphatically against this way of life; but in spite of this it has not lost its attraction for a great number of people.

A small minority are enabled by their constitution to find happiness, in spite of everything, along the path of love. But far-reaching mental changes in the function of love are necessary before this can happen. These people make themselves independent of their object’s acquiescence by displacing what they mainly value from being loved on to loving; they protect themselves against the loss of the object by directing their love, not to single objects but to all men alike; and they avoid the uncertainties and disappointments of genital love by turning away from its sexual aims and transforming the instinct into an impulse with an inhibited aim. What they bring about in themselves in this way is a state of evenly suspended, steadfast, affectionate feeling, which has little external resemblance any more to the stormy agitations of genital love, from which it is nevertheless derived. Perhaps St. Francis of Assisi went furthest in thus exploiting love for the benefit of an inner feeling of happiness.”

Freud claims that genital stimulation is the “pattern” on which we base our search for happiness and our value judgments. If we agree with his views then we have to see our love of friends, politics, art, God, and so on as mere substitutes for genital pleasure rather than as positive sources of happiness. To be sure, they can be sublimations of our libidinal urges into socially acceptable channels that provide some degree of growth and happiness. But they would be substitutes nonetheless. Moreover, many of these efforts at substitution will not lead to healthy sublimations. Rather, they will lead to neurotic traits that, in being socially unacceptable, will bring discontent.

So someone who sublimates his libidinal drive into a love for “all men alike”, like St. Francis of Assisi, is just “avoiding the uncertainties and disappointments of genital love.” In doing so he will either have, on the one hand, an impoverished yet socially respected form of happiness or, on the other hand, an opportunity for repression that leads to neuroses. Either way there is a real loss of the genuine happiness that only comes through sex. Not a very encouraging dilemma.

***

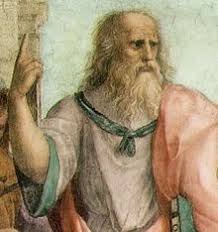

We can turn to Plato for a far more optimistic view of love and it’s relation to our happiness. In his Symposium (Socrates’ speech) we learn that erotic love can lead us away from sexual pleasure towards more comprehensive objects of desire. Socrates describes this process as a movement of the soul away from the changing, imperfect aspects of beauty to the unchanging, perfect Form of Beauty itself. Here is a description of this Form:

“He who has been instructed thus far in the things of love, and who has learned to see the beautiful in due order and succession, when he comes toward the end will suddenly perceive a nature of wondrous beauty (and this, Socrates, is the final cause of all our former toils) – a nature which in the first place is everlasting, not growing and decaying, or waxing and waning; secondly, not fair in one point of view and foul in another, or at one time or in one relation or at one place fair, at another time or in another relation or at another place foul, as if fair to some and foul to others, or in the likeness of a face or hands or any other part of the bodily frame, or in any form of speech or knowledge, or existing in any other being, as for example, in an animal, or in heaven or in earth, or in any other place; but beauty absolute, separate, simple, and everlasting, which without diminution and without increase, or any change, is imparted to the ever-growing and perishing beauties of all other things.” (210e-212b)

The process of approaching the Beautiful Itself is as follows: Eros is detached from individual people and we come to see beauty can be present in many bodies; then we come to value the beauty of the soul and the virtuous laws of the state which guide it; then we come to grasp the beauty of truths found in mathematics and science—truths which are eternal and thus transcend the moving aspects of the body, the soul, and the state (210a-e). Finally, we transcend even these intellectual truths and see, with the eye of the soul, the eternal Form of Beauty that grants beauty to all the previous imperfect imitations of it. This seeing comes suddenly upon the soul after many years of preparation and is wonderful (210e-211d). It enables a new form of procreation to take place—a spiritual or non-physical form. Rather than making something like children or works, the soul is able to give birth to itself as wise and therefore virtuous. The procreation is not an imperfect external image but an internal transformation of the soul that bypasses images completely; and this form of inner procreation has the capacity to bring forth a virtuous soul (212a-e). This transformed soul would have the wisdom capable of intelligently directing its desires. In doing so, it would be divine-like in its autonomy or self-governance. Beautiful bodies, souls, societies, and truths can still pursued. But after the ascent to the Beautiful Itself they can be been enjoyed in ways that lead to virtue and fulfillment.

This journey is what has become known as Plato’s “ladder of love.” It is a venerable, highly influential account that shows just how closely connected desire, even base sexual desire, is to a Form of supersensible beauty that shines to our soul from another world.

***

These two views of Eros and its relation to our happiness are radically opposed as Francis Cornford points out in his article “The Doctrine of Eros in Plato’s Symposium” (quoted in Plato II: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Gregory Vlastos):

“The Platonic doctrine of Eros has been compared, even identified, with modern theories of sublimation. But the ultimate standpoints of Plato and of Freud seem to be diametrically opposed. Modern science is dominated by the concept of evolution, the upward development from the rude and primitive instincts of our alleged animal ancestry to the higher manifestations of rational life. The conception was not foreign to Greek thought. The earliest philosophical school had taught that man had developed from a fish-like creature, spawned in the slime and warmed by the heat of the sun. But Plato had deliberately rejected this system of thought. Man is for him the plant whose roots are not in the earth but in the heavens.” (128).

It seems to me that Cornford is right to draw this strong contrast. Must we choose between them? Not necessarily: both views might be wrong. And perhaps we can take aspects of both and forge a new account. But, supposing for a moment we must choose between them, we can ask:

Could it be that Plato’s breathtaking and influential vision of Eros and psyche is nothing more than an eloquent and elaborate sublimation of his libidinal energy? Was Plato, like St. Francis, playing it safe and retreating into a philosophical world of transformed Eros in order to protect himself against “the loss of the object”? Is he really moving us away from fulfillment with his vision of directing Eros to more and more abstract and comprehensive objects of enjoyment?

Or is it the case that Freud, in reducing our happiness to the lowest level on Plato’s ladder of love, is actually orienting us towards a life of vice and unhappiness in which there is little to no awareness of that which we need to become virtuous, namely, the Beautiful Itself?

Go here for my posts on Plato.

Go here for my posts on beauty.

Go here for my posts on love.

Interesting pints of both these Gentlemen. I, on the other hand, not only believe, but have experienced a great happiness that comes from walking away from the physical act as sexual things (though some of it has to do with my aging years, in which I have found much more important things, as well as my physical chemistry having changed and thus has helped me in this endeavor). I have reached a point, where as St. Francis had done, am able to focus my concentration more and more on the spiritual things rather than attempting to gain pleasures from material objects all of which MUST decay and rot, in accordance with the Laws of Physics)