254. Some Political Implications of Leibniz’s Principles of Continuity, Perfection, and Sufficient Reason

The enlightenment philosopher and polymath G. W. Leibniz (1646-1716) was a master at articulating various general and fundamental principles and applying these principles to philosophical problems. Principles are statements of basic laws, truths, or rules from which other laws, truths, or rules are derived. In this post I will discuss three of his most famous principles – the principle of continuity, the principle of perfection, and the principle of sufficient reason – and show how they have interesting and often overlooked political implications that can help us in our efforts to reduce the widespread polarization, demonization, and lack of civility around us.

***

The principle of continuity asserts, as he puts it in his Discourse on Metaphysics (1686), that “nature never makes leaps” (see Discourse on Metaphysics and Other Essays, Hackett Publishing, p. 56). This “entails that one always passes from the small to the large and back again through what lies between, both in degrees and in parts, and that a motion never arises immediately from rest nor is it reduced to rest except through a lesser motion” (56). To think otherwise is “to know little of the immense subtlety of things, which always and everywhere involves an actual infinity” (57).

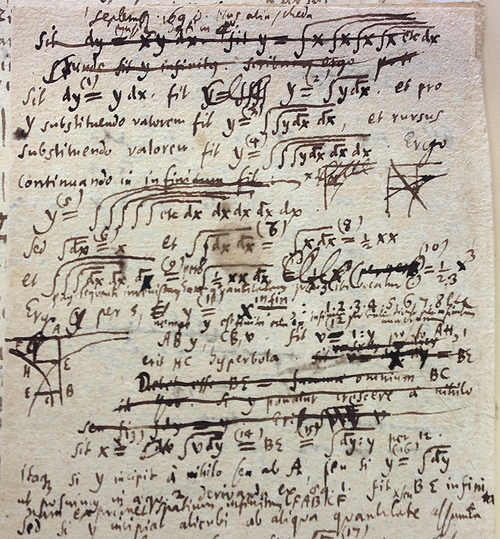

This principle has an impressive scope of application. For example, Leibniz claims it shows that atoms (in the literal meaning of indivisible objects) are unintelligible. He observes that when one thing collides with another and moves another, the movement can only take place continuously if each object has parts that are in turn made of parts, etc. It is the movement of these parts, however subtle and unseen, that allows for the continuous and partially elastic movement that is experienced in the collision as these images of a golf ball convey:

If atoms exist then they have no parts and therefore their movement—whether acceleration or deceleration—would not occur in a gradual, continuous manner as their internal parts shift this way and that; rather, their movement would be an immediate leap from one state to another unconnected to any previous event. Indeed, the leap would be preceded by nothing which would violate another of Leibniz’s favorite principles, the principle of sufficient reason, which asserts that for every fact and true proposition there is a sufficient reason why it is thus and not otherwise (see his Monadology section 32). This would leave us with absurd motions with no explanation – something obviously devastating for science.

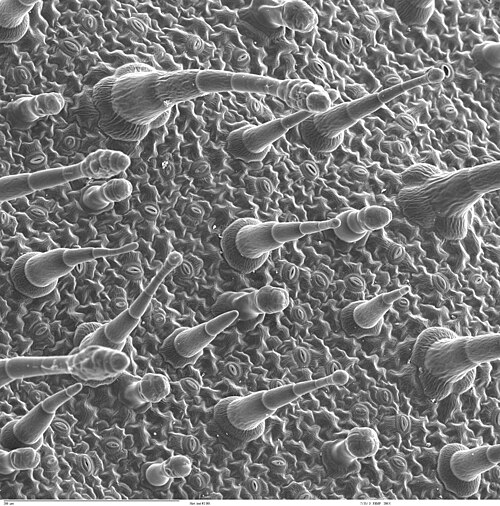

He also argues against the idea that a thing could become completely inactive. For then when it does act we would have an action that, rather than arising continuously, would be a discontinuous leap. So what appears to be at rest is actually imperceptibly active. Similarly, a soul with absolutely no thought at all is unintelligible. For then conscious thought would be a leap from non-thinking to thinking. So Leibniz postulates the existence of unconscious thought out of which conscious thought can continuously arise (Leibniz thereby made use of unconscious thought some 200 years before Freud). Leibniz also claims that “because of insensible variations, two individual things cannot be perfectly alike and must always differ in something over and above number” (57). Forms may seem to be the same but, upon closer inspection with a microscope, we will see endless variations. Thus our knowledge that insensible perceptions exist “serves to explain why and how two souls of the same species, whether human or otherwise, never leave the hands of the creator perfectly alike, and why and how each of them always has its original relation to the point of view it will have in the universe” (58).

An image of a unique leaf under a microscope. As Leibniz says, “Never are two eggs, two leaves, or two blades of grass in a garden to be found exactly similar to each other.” Leibniz passionately welcomed Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovery of microorganisms in the 1670s as empirical evidence for his principle of continuity.

Perhaps most interestingly, the principle of continuity, in ruling out gaps or any kind of void in the universe, implies that nothing exists in isolation and that every agent affects, and is affected by, everything else: “All things conspire” (sympnoia panta) as the ancient Greek Hippocrates asserted (Monadology section 61). In fact, Leibniz goes further and claims that “each simple substance has relations that express all the others, and consequently, that each simple substance is a perpetual, living mirror of the universe” (Monadology, section 56).

Naturally, in all these examples we will not necessarily perceive all the continuities that exist and make our world rationally intelligible. But they are there as these three memorable passages from The Monadology assert:

“67. Each portion of matter can be conceived as a garden full of plants, and as a pond full of fish. But each branch of a plant, each limb of an animal, each drop of its humors, is still another such garden or pond.

68. And although the earth and air lying between the garden plants, or the water lying between the fish of the pond, are neither plant nor fish, they contain yet more of them, though of a subtleness imperceptible to us, most often.

69. Thus there is nothing fallow, sterile, or dead in the universe, no chaos and no confusion except in appearance, almost as it looks in a pond at a distance, where we might see the confused and, so to speak, teeming motion of the fish in the pond, without discerning the fish themselves.”

***

I think this brief overview gives us enough understanding to see how the principle of continuity might be applied to politics. We can approach this application with the help of this interesting passage:

“If we thought in earnest that things we do not consciously perceive are not in the soul or in the body, we would fail in philosophy as in politics, by neglecting the mikron, imperceptible changes. But an abstraction is not an error, provided we know that what we are ignoring is really there. This is similar to what mathematicians do when they talk about the perfect lines they propose to us, uniform motions and other regular effects, although matter (that is, the mixture of the effects of the surrounding infinity) always provides some exception. We proceed in this way in order to distinguish various considerations and, as far as is possible, to reduce effects to their reasons, and foresee some of their consequences. For the more careful we are not to neglect any consideration we can subject to rules, the more closely practice corresponds to theory. But only the supreme reason, which nothing escapes, can distinctly understand the whole infinite, all the reasons, and all the consequences” (57).

Since we are in a world full of infinite gradations and continuous complexity, since we are in a world of imperceptible changes or mikron, we must be incredibly vigilant as we employ useful abstractions in our language, diagrams, models, ideas, etc. Simplifying things has a place as long as we are aware that we are simplifying. But when it comes to truly understanding the nature of things we must be acutely aware of how our simplifications, and indeed all our intellectual efforts, are bound misrepresent the infinite continuities of the world which only God’s supreme reason can fathom. And, as he says, we are bound to fail in politics as well.

***

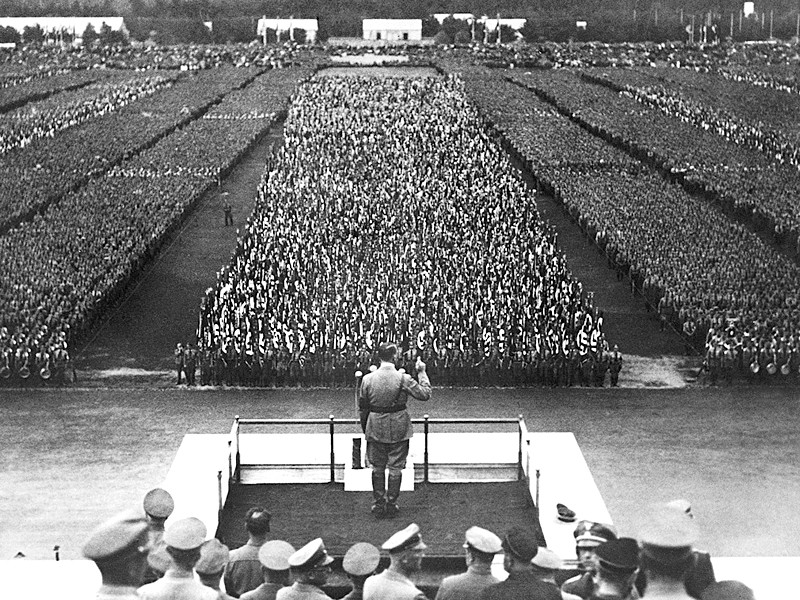

As we all know, we currently live in a highly politicized world permeated with differences that divide people and make them think they have little or even nothing in common. Such thoughts lead people to sort themselves into like-minded and exclusive groups where they become more extreme versions of themselves and judge others as the extremists. Fascism is an extreme version of this group polarization dynamic insofar as it requires a strictly exclusive form of nationalism. It also takes to an extreme the negation of individuality we see in polarized scenarios with their group think mentality. Hannah Arendt, in her classic work The Origins of Totalitarianism (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), perfectly expresses this negation when she observes that “Total domination, which strives to organize the infinite plurality and differentiations of human beings as if all of humanity were just one individual is possible only if each and every person can be reduced to a never-changing identity of reactions, so that each of these bundles of reaction can be exchanged at random for any other” (438).

Nazi Nuremberg rally: so-called aesthetic and intellectual uniformity concealing the mikron which insures unique individuality and undermines any dream of exclusivity

But given the implications of the principle of continuity sketched above, we can see that this dehumanizing pathology of uniformity is doomed since no two people are the same and everyone’s perspective on the world matters. And nationalistic appeals to a master race discontinuous with others are doomed as well since the fact that “all things conspire” means humans are connected genetically, psychologically, culturally, and, as far as Leibniz is concerned, spiritually. So, whether we are talking about fascism or less extreme forms of group polarization, a world full of continuity and the mikron implies the uniqueness of every individual and “always provides some exception” to our inadequate labels and stereotypes. And such a world includes points of contact between us all whether we realize it or not (one way Leibniz explores these points is through language since we “must interrelate the languages of various peoples, and one should not make too many leaps from one nation to another remote one unless there is sound confirming evidence, especially evidence provided by intervening peoples.”).

I think these two consequences of continuity result in many things helpful to political action, namely, a strong sensitivity to context, a respect for unique individuals with unique perspectives, a suspicion of generalizations, a desire for theory to correspond to practice, a realization that ongoing inquiry with others is crucial since we are all finite and fallible beings enmeshed in a world of infinite changes, and a belief that we are all connected in many ways. Perhaps acting in accordance with these results can help reduce things that are usually a function of denying them such as widespread polarization, demonization, and lack of civility.

***

Towards the end of his essay On the Ultimate Origination of Things (1697), Leibniz makes the optimistic claim that there is unbounded progress in the universe despite various temporary setbacks. This fits well with his Christianity and vision of a world governed by God who created, as he famously put it, “the best of all possible worlds.” But he also thinks progress follows from his principle of continuity as his concluding words to the essay show:

“And there is a ready answer to the objection that if this were so, then the world should have become Paradise long ago. Many substances have already attained great perfection. However, because of the infinite divisibility of the continuum, there are always parts asleep in the abyss of things, yet to be roused and yet to be advanced to greater and better things, advanced, in a word, to greater cultivation. Thus, progress never comes to an end” (48).

Hannah Arendt

These ideas have political implications as well. In her book The Human Condition (1958), Hannah Arendt wrote: “The fact that man is capable of action means that the unexpected can be expected from him, that he is able to perform what is infinitely improbable. And this again is only possible because each man is unique, so that with each birth something uniquely new comes into the world” (see chapter 5). She believed this “natality” or capacity to begin anew was crucial to political action which can easily be smothered by pessimistic acquiescence to the status quo and fatalist narratives. Leibniz offers us similar ideas some three centuries earlier. In a world of the mikron we can never say never since there is always the possibility that some dynamics asleep in the abyss of things will awaken and contribute to a better world. Thus Leibniz’s principle of continuity offers us hope by reminding us that causes for pessimism or cynicism, while real enough to us from our limited perspective, are concealing a vast number of positive potentials just like a sterile-looking pond is concealing a vast number of organisms. We should remain open to such potentials and be prepared to actualize them for a better world. To be a pessimist is, as we saw above, to know little “of the immense subtlety of things, which always and everywhere involves an actual infinity.”

However, the key word is better since Leibniz believed, in accordance with the principle of continuity itself, that our happiness lies in the very activity of striving – continuously striving – for perfection since “progress never comes to an end.” Leibniz defines perfection as an optimal combination of variety and order: as much diversity of life as possible with as few underlying laws as possible. The infinite gradations of the principle of continuity follow from this principle of perfection since the existence of discontinuous gaps and exact repetitions would demonstrate less diversity than there could be – something impossible given God’s perfection. Now, scientists are certainly guided by this principle (for example in their search for a theory of everything which seeks one fundamental force capable of explaining all the phenomena in the universe). But it should also guide those in politics to maximize as much human diversity, freedom, and interconnection as possible within the confines of a simple set of just laws. This would be the opposite of the fascist vision we saw above where freedom, diversity, and various forms of interconnection with others are undermined by unjust laws. Leibniz’s preferred way to realize this limited vision of perfection would be through a just monarch, wise senators, and rational citizens.

Chateau de Versailles – Galerie des Glaces (photo by Myrabella/Wikimedia Commons). The seemingly infinite richness existing within geometrical order of Baroque art nicely expresses Leibniz’s principles of perfection and continuity.

***

It is important to keep in mind that for Leibniz human governments are imperfect manifestations of the perfect Government of God. Leibniz thinks the best way to do one’s duty as a citizen of this Government is to love others by helping them understand manifestations of God’s perfection in metaphysics, physics, psychology, mathematics, and, most intimately, the soul since the soul itself is a monad, a simple immaterial substance or pure unity, in which there is a rich diversity. This unity within diversity is found in perception: “The passing state which involves and represents a multitude in the unity or in the simple substance is nothing other than what one calls perception” (Monadology section, 14). It is also manifested in any conscious thought whatsoever: “We ourselves experience a multitude in a simple substance when we find that the least thought of which we are conscious involves variety in its object” (Monadology section, 16). Leibniz argues governments should cultivate an understanding of these manifestations of perfection by supporting institutions of learning which expand the “Empire of Reason” to all humans who, by possessing self-consciousness and reason, are “images of divinity” (Leibniz was a tireless advocate of such institutions).

Obviously these individual and institutional efforts to make a more rational world are bound to have far reaching political implications since unjust political power often thrives when people are incapable of rational evaluation and especially incapable of seeing both the rich diversity and underlying unity in the world. And Leibniz’s theism adds an encouraging support since, despite all the failures, tragedies, and evil of the world, justice will be served by God’s “supreme reason” which, as we saw above, “can distinctly understand the whole infinite, all the reasons, and all the consequences” of the world’s sublime variety:

“Finally, under this perfect government, there will be no good action that is unrewarded, no bad action that goes unpunished, and everything must result in the well-being of the good, that is, of those who are not dissatisfied in this great state, those who trust in providence, after having done their duty, and who love and imitate the author of all good, as they should, finding pleasure in the consideration of his perfections according to the nature of genuinely pure love, which takes pleasure in the happiness of the beloved” (Monadology, concluding section 90).

Of course, if we are to find any of these theological reflections philosophically convincing we will need an argument for God’s existence. My favorite Leibnizian argument for God is his argument from eternal truths which I discuss here. But, staying with principles in this post, we can turn to Leibniz’s argument for God from the principle of sufficient reason. This passage from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry “Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz” offers a helpful summary:

“As we have seen, the Principle of Sufficient Reason is one of the bedrock principles of all of Leibniz’s philosophy. In the Monadology, Leibniz appeals to PSR, saying that even in the case of contingent truths or truths of fact there must be a sufficient reason why they are so and not otherwise. (Monadology §36) But, since each particular truth of fact is contingent upon some other (prior) truth of fact, the reason for the entire series of truths must be located outside the series, and this ultimate reason is what we call God. (Monadology §37)” (See section 7.1.2).

And this passage shows how Leibniz builds on this argument for a necessary being to offer a more comprehensive account of the nature of God:

“In the Theodicy, Leibniz fills out this argument with a fascinating account of the nature of God. First, insofar as the first cause of the entire series must have been able to survey all other possible worlds, it has understanding. Second, insofar as it was able to select one world among the infinity of possible worlds, it has a will. Third, insofar as it was able to bring about this world, it has power. (Leibniz adds here that “power relates to being, wisdom or understanding to truth, and will to good.”) Fourth, insofar as the first cause relates to all possibles, its understanding, will and power are infinite. And, fifth, insofar as everything is connected together, there is no reason to suppose more than one God. Thus, Leibniz is able to demonstrate the uniqueness of God, his omniscience, omnipotence, and benevolence from the twin assumptions of the contingency of the world and the Principle of Sufficient Reason. (Theodicy §7: G VI 106–07/H 127–28)” (See section 7.1.2).

***

Leibniz is not known for being a political philosopher and it is true that his writings prioritize other concerns. But I hope to have shown that his closely related principles of continuity, sufficient reason, and perfection have plenty of interesting political implications which can empower us to deal with contemporary political problems. Of course, both the principles and the implications I’ve drawn raise many questions and require more analysis than I provide here (for a helpful critical assessment of all three principles and much more in Leibniz’s philosophy, see Benson Mates’ The Philosophy of Leibniz: Metaphysics and Language, especially chapter 9). But I think the foregoing shows they are clear enough for us to glean some helpful insights from them. Let’s review these insights.

We first saw how an understanding of the principle of continuity can result in a sensitivity to context, a respect for unique individuals with unique perspectives, a suspicion of generalizations, a desire for theory to correspond to practice, a realization that ongoing inquiry with others is crucial since we are all finite and fallible beings, and a belief that everyone is connected in an infinite number of ways. All these ideas can inspire us to look for ways to reduce the widespread polarization, demonization, and lack of civility that so often follow from denying one or more of these results.

We then saw how continuity implies never-ending progress and that, contrary to our limited and often discouraging perspectives, conditions for growth may be lurking in the mikron or imperceptible changes around us. The belief in such conditions of progress can help us avoid various forms of pessimism and cynicism that destroy political action by destroying the belief that things can change for the better.

Finally, we saw how the principle of sufficient reason can be used to demonstrate the existence of God whose creation of the universe is guided by the principle of perfection, namely, making as much diversity as possible with as few laws as possible. One political implication of this principle is that societies and governments should maximize as much human diversity, freedom, and interconnection as possible within the confines of a simple set of just laws. Another is that we should help others understand manifestations of perfection in metaphysics, physics, psychology, mathematics, and so on in order to spread the “Empire of Reason” throughout the world. Being part of this Empire requires we see people as neighbors worthy of love rather than strangers worthy of hatred. We are, after all, related to them in an infinite number of ways through the principle of continuity. And according to Leibniz loving is a matter of cultivating understanding in others and engaging in ongoing rational inquiry with them for a better world. In the end, this idea of cultivating an Empire of Reason is perhaps the most political of all of Leibniz’s ideas since without reason and love we can’t expect intelligent and just societies to emerge and continue.

Naturally, all these political implications can be difficult to transfer from theory to practice. Leibniz certainly acknowledged the depths of evil in the world and was no delusional optimist despite many who, like Voltaire, have claimed otherwise. But he would be beseech us to keep striving for political perfection with the belief that in God we have an eternal political ally whose infinite mind contains the truths upon which we continuously draw and whose omnipotent will ensures perfect justice and a greater good will ultimately prevail.

***

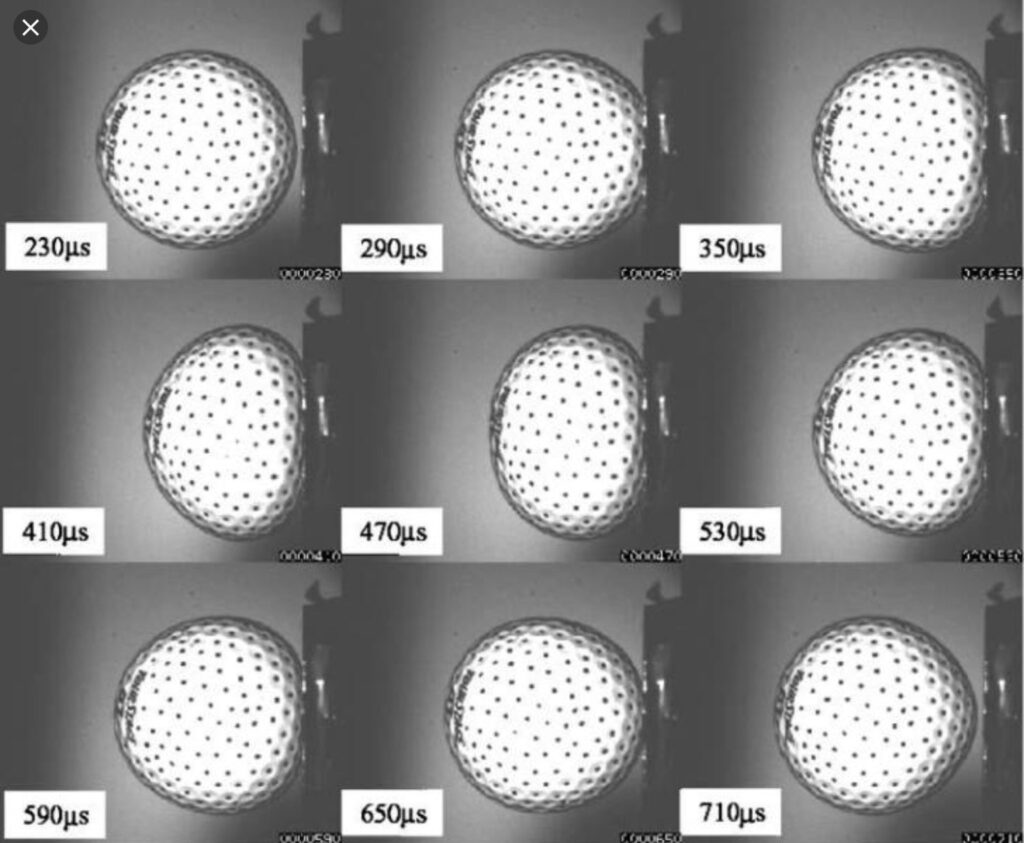

A page from Leibniz’s notes on calculus which he invented (independently of Newton) and which mathematically expresses his principle of continuity. Nicholas Rescher, in his essay “Leibniz and the Concept of a System,” points out how it also expresses Leibniz’s new vision of a system based on his vision of perfection: “For him, the ideal model of a cognitive system was provided not by the geometry of the ancient Greeks but by the physics of seventeenth century Europe. In his view, the calculus was not just a convenient mechanism for solving mathematical problems, it provided a new model of rational systematization, for implementing that “principle of determination in nature which must be sought by maxima and minima.” Such an instrument provides, as Leibniz saw it, a tool for discerning, amidst an infinite variety of diverse phenomena, those operative principles (e.g., Snell’s law in optics) through which the desiderata of rational economy are instituted in the nature of things. With the Euclidian axiomatization we have a finite basis of elements (axioms and definitions) from which these are extracted by finite deductive processes. With the calculus-and especially the calculus of variations-we are put in a position of being able to survey an infinite range of alternatives and to discern amidst a literally endless variety of possibilities those particular determinatives indicated by the principles of rational economy. Here, with this system-oriented resort to the mechanism of the calculus, we once again see at work the thought of Leibniz a Renaissance-inspired busting of the classical bonds.” Thus calculus expresses the principle of perfection, the principle of continuity that flows from it, and the principle of sufficient reason as well. See Rescher’s book On Leibniz (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), p. 115.

For my other posts on Leibniz, go here.