250. Freud vs. the Socrates Syllogism: the Uncanny Denial of Death

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Introduction

I recently reread Sigmund Freud’s brilliant essay “The Uncanny” (1919) and I came across a fascinating claim which I failed to adequately process in the past. It has to do with his psychoanalytic analysis of one of the most famous and obviously sound arguments in the history of philosophy. If he is right then there are serious ramifications that should be considered. Let me set the stage with a few elementary ideas of logic so, if you don’t know them already, you can fully appreciate his critique.

A Few Basic Ideas in Logic

Logic is the study of arguments. But in logic an argument is not a disagreement. Rather, it is a set of statements that are given in support of another statement. The supporting statements are called premises and the statement that is supported is the conclusion. Typically we divide arguments into two categories: deductive and inductive.

Inductive arguments present a conclusion as only following from the premises with some degree of probability. Such arguments are very common: we use them when we generalize from a sample, when we argue based on analogies, when we infer effects from causes (predictions), and when we infer causes from effects (arguments to the best explanation). When we evaluate inductive arguments we (1) want to see if the premises are true and (2) if they provide strong or weak support for a more or less probable conclusion. If the premises appear to support a highly probable conclusion then the argument is strong; if not, the argument is weak. If we have a strong argument and true premises then we say the induction is cogent; if we don’t have all true premises and/or weakness then we have an uncogent induction. Consider this example:

“I have met about 8 philosophers in my life and they were all annoying people. So most likely this philosopher I will meet today will be annoying.”

This is a weak induction. But we can make it much stronger if we had, for example, premises that reflect a random and much larger sample. If the information in such premises was indeed true, then we would have both a strong and cogent inductive argument.

Now a deductive argument presents a conclusion as following necessarily from the premises. If the premises are true then the conclusion is guaranteed to be true as well. When we evaluate deductive arguments we are looking for soundness. A sound deductive argument is one which (1) has premises that are true and (2) has validity which means the conclusion logically follows from the premises. Consider this example:

All men are elephants.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore Socrates is an elephant.

Valid…but not sound! The conclusion logically follows from the premises but premise 1 is false and thus the conclusion is as well.

Socrates

The Socrates Syllogism

A syllogism is a deductive argument that have two premises each of which (1) shares a term with the conclusion and (2) shares a common or middle term not present in the conclusion. The science of syllogisms, which goes back to Aristotle, is quite complex and very fascinating. For example, it turns out there are 256 possible syllogisms in categorical logic but only 24 valid forms. And of these 24 only 15 are unconditionally valid and 9 are conditionally valid. But for now let’s look at the most famous example of a syllogism:

All humans are mortal

Socrates is a human

So Socrates is mortal.

This appears to be a sound deductive argument since we have both validity and true premises (humans may, of course, become immortal someday but for now things looks grim). As a result, the conclusion is guaranteed to be true. As mentioned above, most of our reasoning is inductive in nature and we live in an uncertain world of probabilities with few guarantees. So it is nice to know we can always return to the air tight logic of the Socrates Syllogism and find an argument, even one about our mortality, which is actually convincing. Right?

Freud’s Essay “The Uncanny”

Wrong! Or, at least, if Freud’s critique of it is right. To approach his critique, let’s take a brief look at the thesis of his essay “The Uncanny” (first published in Imago, Bd. V., 1919; reprinted in Sammlung, Fünfte Folge. I’ll be using a translation by Alix Strachey). Obviously Freud is well known for claiming our unconscious mind influences our actions, motives, and beliefs in many ways. One of the goals of his psychoanalysis was to unearth the motives and contents of the unconscious in order to give people some degree of freedom from various afflictions. This unearthing was typically undertaken with the help of dream interpretation, free association, the analysis of parapraxes (Freudian slips), resistance to analysis, and the phenomenon of transference. But the aesthetic experience of the uncanny can also help in this effort since, according to Freud, it betrays a return of the repressed: something that we have repressed is activated by the uncanny thing and this activation is what generates the unease that what we take to be familiar is now strangely unfamiliar at the same time. In section one he begins with an impressive etymological analysis which finally leads him to this insight:

The Penguin book which includes “The Uncanny” and Freud’s other essays on aesthetics

“In general we are reminded that the word heimlich is not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas, which without being contradictory are yet very different: on the one hand, it means that which is familiar and congenial, and on the other, that which is concealed and kept out of sight….Thus heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops towards an ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich. Let us retain this discovery, which we do not yet properly understand, alongside of Schelling’s definition of the “uncanny” [F.W.J. Schelling, German philosopher (1175-1854)]. Then if we examine individual instances of uncanniness, these indications will become comprehensible to us.”

He then moves onto various examples such as damage to one’s eyes, dolls, doppelgängers, repetitions, improbable coincidences, severed limbs, epileptic seizures, evil people, silence, darkness, the belief that thoughts and intentions can generate real effects (for example, the evil eye), psychoanalysis itself, and, yes, women’s genitals. After his overview and analysis of examples, he offers his groundbreaking explanation:

“This is the place now to put forward two considerations which, I think, contain the gist of this short study. In the first place, if psychoanalytic theory is correct in maintaining that every emotional affect, whatever its quality, is transformed by repression into morbid anxiety, then among such cases of anxiety there must be a class in which the anxiety can be shown to come from something repressed which recurs. This class of morbid anxiety would then be no other than what is uncanny, irrespective of whether it originally aroused dread or some other affect. In the second place, if this is indeed the secret nature of the uncanny, we can understand why the usage of speech has extended das Heimliche [the homely, familiar] into its opposite das Unheimliche [unhomely, unfamiliar]; for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or foreign, but something familiar and old—established in the mind that has been estranged only by the process of repression. This reference to the factor of repression enables us, furthermore, to understand Schelling’s definition of the uncanny as something which ought to have been kept concealed but which has nevertheless come to light.”

Magic (1978)

For example, when we were children, we saw things around us as alive, as animated. We spoke to toys and related to them as subjects. The books we read and the images we saw often depicted a world of talking objects and animals to which we related in a meaningful way. According to Freud, we were animists. But then we grew up and learned that our beloved toys are just objects with no life and that plants and animals are not human. We came to see the world as matter in motion and became scientific, realistic, mature, etc. But in many people these animistic tendencies don’t simply disappear: they are repressed and disappear into the unconscious. So, when a mature adult gets unsettled by a ventriloquist’s dummy like the one above from the movie Magic, Freud would say that what is familiar—an object that is simply wood—has suddenly become unfamiliar in light of repressed beliefs about dolls having life and being subjects. Thus the doll is perceived as both dead and alive, both familiar and unfamiliar, at the same time. But not familiar and unfamiliar in the same respect which would be contradictory. Rather, we (1) see the doll in one respect as alive from the perspective of our repressed, animistic tendencies in the unconscious and (2) see the doll in another respect as dead from the perspective of our conscious, scientific outlook. So Freud’s introduction of the unconscious helps us avoid contradiction and offers an explanation of how we can have such a disturbing and ambiguous feeling.

Freud’s Attack on the Socrates Syllogism

We are now ready – as ready as we can be with Freud’s surprising ideas – for his critique of the Socrates Syllogism. Here is Freud’s argument that, despite the undeniable conscious logical appeal of the deduction, our uncanny experiences associated with death show that no one actually believes they will die from the perspective of the illogical unconscious. And this means that no one really believes the first premise that all humans are mortal – an outlandish claim for sure but one which Freud thinks various aspects of culture support:

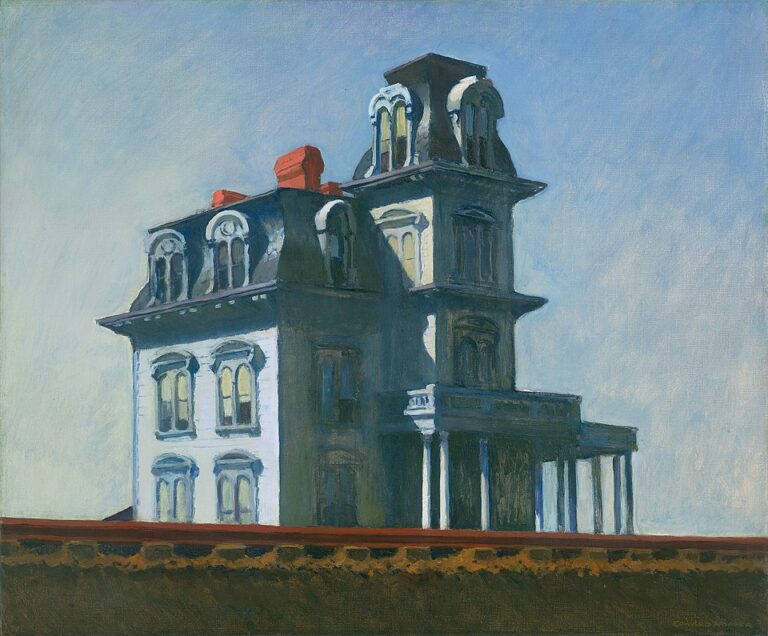

Edward Hopper, House by the Railroad (1925)

“Many people experience the feeling in the highest degree in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead, and to spirits and ghosts. As we have seen, many languages in use today can only render the German expression “an unheimliches house” by “a haunted house.” We might have begun our investigation with this example, perhaps the most striking of all, of something uncanny, but we refrained from doing so because the uncanny in it is too much mingled with and in part covered by what is purely gruesome. There is scarcely any other matter, however, upon which our thoughts and feelings have changed so little since the very earliest times, and in which discarded forms have been so completely preserved under a thin disguise, as that of our relation to death. Two things account for our conservatism: the strength of our original emotional reaction to it, and the insufficiency of our scientific knowledge about it. Biology has not yet been able to decide whether death is the inevitable fate of every living being or whether it is only a regular but yet perhaps avoidable event in life. It is true that the proposition “All men are mortal” is paraded in text-books of logic as an example of a generalization, but no human being really grasps it, and our unconscious has as little use now as ever for the idea of its own mortality. Religions continue to dispute the undeniable fact of the death of each one of us and to postulate a life after death; civil governments still believe that they cannot maintain moral order among the living if they do not uphold this prospect of a better life after death as a recompense for earthly existence. In our great cities, placards announce lectures which will tell us how to get into touch with the souls of the departed; and it cannot be denied that many of the most able and penetrating minds among our scientific men have come to the conclusion, especially towards the close of their lives, that a contact of this kind is not utterly impossible. Since practically all of us still think as savages do on this topic, it is no matter for surprise that the primitive fear of the dead is still so strong within us and always ready to come to the surface at any opportunity. Most likely our fear still contains the old belief that the deceased becomes the enemy of his survivor and wants to carry him off to share his new life with him. Considering our unchanged attitude towards death, we might rather inquire what has become of the repression, that necessary condition for enabling a primitive feeling to recur in the shape of an uncanny effect. But repression is there, too. All so-called educated people have ceased to believe, officially at any rate, that the dead can become visible as spirits, and have hedged round any such appearances with improbable and remote circumstances; their emotional attitude towards their dead, moreover, once a highly dubious and ambivalent one, has been toned down in the higher strata of the mind into a simple feeling of reverence.”

Science & Society Picture Library – Getty Images

One thing to keep in mind here is that, according to Freud, our unconscious is marked by, among other things, “exemption from mutual contradiction, timelessness, and replacement of external by psychical reality” (see his 1915 essay “The Unconscious”). Given these traits, he can maintain that, despite our grown up and conscious understanding of our mortality, our unconscious can still – and always – maintain its commitment to immortality based on the primary narcissism of childhood. The fact that the reality principle has taught the ego it will die means nothing since the unconscious can replace truths about external reality with a psychical reality of its own and won’t be bothered if reality contradicts it. Indeed, in his essay “Thoughts on War and Death” (1915) Freud argues nothing can contradict it since contradiction requires negation and there is no negation in the unconscious:

“What, we ask, is the attitude of our unconscious towards the problem of death? The answer must be: almost exactly the same as that of primaeval man. In this respect, as in many others, the man of prehistoric times survives unchanged in our unconscious. Our unconscious, then, does not believe in its own death; it behaves as if it were immortal. What we call our ‘unconscious-the deepest strata of our minds, made up of instinctual impulses-knows nothing that is negative, and no negation; in it contradictories coincide. For that reason it does not know its own death, for to that we can give only a negative content. Thus there is nothing instinctual in us which responds to a belief in death. This may even be the secret of heroism.”

The Dangers of Death–Denying Heroism

If Freud is right then there are bound to be serious ramifications since an awareness of our mortality is an important aspect of a healthy personality. Ernest Becker (1924-1974), in his Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death (New York: Free Press, 1973), argues that “the problem of heroics is the central one of human life, that it goes deeper into human nature than anything else because it is based on organismic narcissism and on the child’s need for self-esteem as the condition of his life. Society itself is a codified hero system, which means that society everywhere is a living myth of the significance of human life, a defiant creation of meaning” (7). He goes on to claim that healthy self-development is intimately connected to an awareness of the heroics one is practicing and whether or not this heroics satisfies two “ontological motives”: the need to affirm oneself and the need to yield (251). Unfortunately most of us are shaped by what he calls the Oedipal Project “which is a flight from passivity, from obliteration, from contingency” (36). To exist is, of course, to be enmeshed in all sorts of relations that create dependencies and make us vulnerable. In the face of these relations we long to be self-born. Recall that Oedipus, in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, killed his father and married his mother. By marrying his mother Oedipus is, symbolically, his own father: he is a causa sui or a cause of himself. Such a being would, like God, be necessary, would avoid all contingency and dependency, and would be fully active with no passivity. Alas, existence breaks through and threatens our projects to be necessary and live forever. As a result, we engage in all kinds of destructive and even evil actions to hold contingency and death at bay. But if we can learn to stop denying death then we can learn to avoid the repressions, failures, and dangers of a life lived in accordance with the Oedipal Project. Indeed, we can learn to recognize our limits and be more humble.

I have some issues with Becker’s overall argument but these insights are, I think, important. I agree that the Oedipal Project should be avoided. But if Freud is right then there is little hope that it will be avoided since, as we saw, “it is true that the proposition “All men are mortal” is paraded in text-books of logic as an example of a generalization, but no human being really grasps it, and our unconscious has as little use now as ever for the idea of its own mortality.” This means that we can expect humans, on a regular basis, to engage in the kinds of unhealthy heroics and delusions that continue to cause suffering to themselves and others. Not a nice thought.

Final Thoughts

But is Freud’s attempt to psychoanalyze our confidence in the Socratic Syllogism convincing? My opinion is that he goes too far in claiming that NO human being grasps mortality. In fact, I think his fascinating use of the uncanny to reveal our denial of death may itself be one way we can come to face death. He is certainly right to point out how little we change and this may help us understand the suffering that flows from superstition, irrationality, regression, delusion, phobias, and so on. But in section three he notes: “An uncanny experience occurs either when repressed infantile complexes have been revived by some impression, or when the primitive beliefs we have surmounted seem once more to be confirmed.” “The Uncanny” certainly provides plenty of fascinating candidates for such complexes and beliefs. He may, of course, be wrong about some or even all of them. But if he is right in his general approach then we can use uncanny experiences to understand and address repressed content in order to grow. And we should note that uncanny art can help as well since, as Freud points out towards the end of his essay, there are many more ways to explore uncanny effects in fiction than in real life: “fiction presents more opportunities for creating uncanny sensations than are possible in real life” as long as “the setting is one of physical reality” rather than “an arbitrary and unrealistic setting” such as we find in fantasy, fairy tales, ghost stories, and so on. Freud discusses E.T.A Hoffman’s tale “The Sand Man” at length and thinks Hoffman’s works fit his criterion (“Hoffmann is in literature the unrivalled master of conjuring up the uncanny”). But we can use many other uncanny works of literature, film, and art (see my blogs on the uncanny below for some examples) in our efforts to have aesthetic experiences which can help us honestly face grim facts about death despite various forms of repression. We may fail to to do so. But to rule out success would, I think, go against Freud’s own inspirational dictum which exhorts us to push as far as we can into the underworld: “Where id was, so ego shall be.”

Death’s appearance in Ingmar Bergman’s classic The Seventh Seal

Read Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” here.

For a good overview and critical evaluation of Freud’s thought, go here.

For my other posts on the uncanny go here.

For my post which goes into a little more detail about syllogisms go here.

For my Freud vs. Plato post go here.

For my post on the cognitive and moral value of Halloween which features the uncanny go here.

For my post on the psychology of Medusa go here.

For my post on demonic music which can be uncanny go here.

For my three-post series on Agnes Heller’s theory of home/world which connects to the uncanny go here.

Hi Dwight, I enjoyed this blog post. I especially like your point in the end about how uncanny experiences can serve as growth experiences since it allows insight into the unconscious and our repressed complexes and beliefs.

There are some interesting empirical questions that arise from this. There are certainly individual differences in the experiences of the uncanny in response to a stimulus. This might be connected to early life experiences and associated with current attachment styles. There might be interesting cultural differences as well, based on religious enculturation. Catholics who believe in the body coming back to life might have enhanced uncanny experiences in response to dressed corpses, for example.

I was struck by this: “The answer must be: almost exactly the same as that of primaeval man. In this respect, as in many others, the man of prehistoric times survives unchanged in our unconscious.” This sounds similar in some ways to Jung’s collective consciousness. I wonder what kind of debate Freud and Jung would have about that.

Thanks for reading and commenting Kamil. I think Freud would agree with your point that individual differences, often culturally conditioned, are involved when it comes to how uncanny stimuli are experienced. He does categorize uncanny reactions with reference to either cultural conditioning or universally shared infantile complexes. But he admits that in some cases both will be involved since “primitive beliefs” will condition how certain complexes play out. In some cases it will be hard to distinguish the two.

Interesting connection with Jung – I’ll have to look into it. One thing I do know was that Freud was committed to the death instinct and Jung disagreed with him on that. I wonder, as I type this, how exactly Freud’s claims about no one really accepting their death would fit with his claim that the aim of life is death. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Norton and Company: 1961) he writes:

“Every modification which is thus imposed upon the course of the organism’s life is accepted by the conservative organic instincts and stored up for further repetition. Those instincts are therefore bound to give a deceptive appearance of being forces tending towards change and progress, whilst in fact they are merely seeking to reach an ancient goal by paths alike old and new. Moreover it is possible to specify this final goal of all organic striving. It would in contradiction to the conservative nature of the instincts if the goal of life were a state of things which had never yet been attained. On the contrary, it must be an old state of things, an initial state from which the living entity has at one time or other departed and to which it is striving to return by the circuitous paths along which its development leads. If we were to take it as a truth that knows no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons—becomes inorganic once again—then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones’” (32).

I suppose his claim that no one accepts their death can be reconciled with this because the death instinct is unconscious and so our conscious ego can go on in accordance with Eros thinking it is growing when it is really seeking death in a roundabout way. But this, like his analysis of the uncanny, seems to be another example of Freud telling us all something about death that he has won from the underworld, something that suggests we can learn to accept death after all. If this is wrong then psychoanalysis seems to be in a tragic predicament indeed: it can unearth facts that we, as a conscious agents, can never accept or intelligently act upon. Also, in my post I quoted him saying that “Our unconscious, then, does not believe in its own death; it behaves as if it were immortal.” I wonder: if the seat of the death instinct is the unconscious how can the unconscious not believe in its own death?