109. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and J.S. Mill

Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer wasn’t allowed to join in those reindeer games. The games, that is, of the normal reindeer, the ones that looked like each other. He was shunned as a misfit who wasn’t worth much. After all, worth comes from how one looks and how well one can conform to the images that society deems acceptable. Right? Wrong! Rudolph’s glowing red nose ended up saving the day because it was so different. Maybe people who don’t fit in to the norm are useful after all, especially when abnormal conditions are at hand. In a diverse, changing world we cannot expect intelligent adjustments to occur if we don’t have diverse people with diverse powers. To be sure, it would’ve been nice if the other reindeer could’ve simply accepted Rudolph for who he was and not because he, like Thomas the Train, was useful after all. But the point of the story is still important despite the unfortunate limitations of the reindeer.

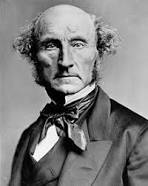

Indeed, the point of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was made, with a bit more philosophical finesse, by John Stuart Mill in his work On Liberty (1859). Mill argues that a truly free society will, among other things, allow people to pursue what makes them happy as long as they don’t harm other people by violating their rights. In chapter three he argues for this claim. One reason he gives is that human nature is not like a machine “but a tree which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing”. To not allow people to develop their interests and pursue happiness in their own way is to threaten the very essence of human nature. Not a bad reason. But a second and related reason he gives is that by allowing people to do their thing we might all benefit from the differences they develop. True, the differences that are developed aren’t always useful to say the least. But the ones that are useful “are the salt of the earth; without them, human life would become a stagnant pool”. But this salt cannot flourish in social contexts that do not celebrate differences. In 1859 Mill could write this: “At present individuals are lost in the crowd. In politics it is almost a triviality to say that public opinion now rules the world”. Are we any different, lost as we are in a world of images every where we turn? I doubt it. So what are we do to? Mill suggests, among other things, a cultivation and celebration of eccentricity: “Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric.” The fact that so few people are eccentric or tolerate eccentricity is “the chief danger of our time”. Mill goes so far as to say that whole societies can collapse if conformity rules the day. By celebrating eccentric individuality we can hope to gain “new truths”, “commence new practices”, and “set the example for more enlightened conduct and better taste and sense in human life”.

In other words, don’t frown on those strange red noses you don’t recognize. And don’t just tolerate them. Try and celebrate those who, to borrow a term Soren Kierkegaard used in his book Two Ages, have become “unrecognizable”. Try and celebrate the eccentricities as long as they don’t violate people’s rights. See them as potentials for developing a rich pool of life that can creatively and intelligently evolve rather than becoming a stagnant pool of conformity. After all, a society full of conformists “would not resist the smallest shock from anything really alive, and there would be no reason why civilization should not die out, as in the Byzantine Empire”. In doing so, you may find yourself and others in what Mill calls an “atmosphere of freedom” that can bring forth “a greater fullness of life”.

For an application of some of Mill’s ideas in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, go here.

For my post on Peter Simpson’s critique of the harm principle, go here.

For my post on the 2016 election and Mill, go here.