93. Is Art Just Imitation?

The imitation theory of art is the oldest philosophy of art we have in the Western philosophical tradition. The theory has its philosophical roots in ancient Greece with Plato and Aristotle and continues to be one very popular way to identify and evaluate art. The theory proposes that art is essentially an imitation of something like nature or human action. This theory takes issues of resemblance, depiction, representation, and interpretation to be central. The process of identifying art will obviously involve reference to an original and the imitation. Traditionally, this process of identification opens up an ontological distinction, that is, a distinction about existence, between reality and appearance: the original is considered real and the imitation is less real than the original. And this distinction often maps onto an epistemological distinction, or a distinction regarding knowledge: the imitation, being an appearance of reality, is sometimes not considered an object of knowledge like the original is (or is capable of giving us less knowledge than the original is). The process of evaluation will often focus on the accuracy of the imitation, the value of that which was imitated, why the imitation was undertaken, and whether the imitation has desirable political, moral, or sociological consequences.

Obviously this approach can work in many cases. We can see a painting of a landscape by Van Gogh and immediately identify it as art from all the other things in the room that were made without any imitative dimension whatsoever like a chair, a spoon, and a television set. And based on the details and skill of the imitation we can evaluate the painting as much better than a picture of the landscape by, say, a five year old. But like all theories of art, it runs into a set of criticisms. Here are two for your consideration.

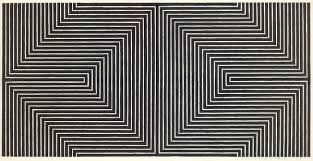

(1) One way to object to the imitation theory is to point out that plenty of art doesn’t seem to resemble or depict any object. Thus while some art does, like landscape painting and realistic sculpture, plenty does not such as abstract painting, instrumental music, lyric poetry, and avant-garde expressive dance.

Frank Stella, Black Study 1 (1968) Does this painting really imitate anything?

This would be a disaster for any theory that seeks to account for all or most of art rather than exclude it. To be sure, there may be ways to stretch our understanding of imitation to account for these elusive art forms. For example, philosopher Richard Eldridge thinks instrumental music may convey ideas about action despite its inability to literally depict something:

“Works of pure instrumental music do not normally visually or audibly depict particular sensible objects, scenes, or even emotions, but they do invite us to think about action, in particular about abstract patterns of resistance, development, multiple attention, and closure that are present in actions, and they invite us to these thoughts in and through perceptual experience of the musical work itself”.[1]

Is this convincing? And can we make similar adjustments for other forms of art? If not, then the imitation theory would seem far too restricting and we would have to supplement it with other theoretical approaches in our account of art.

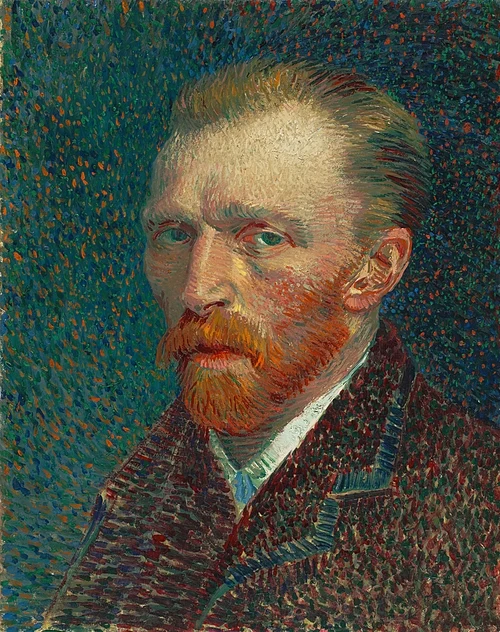

(2) The second main objection to the theory arises when we realize that imitation typically does not—and probably should not—mean exact duplication of something. We typically assess the worth of an imitation by how, on the one hand, it resembles the object it depicts and, on the other hand, how it adds to this depiction something imaginative from the artist’s perspective: something new and non-realistic. We typically do not praise art for copying. We want to see how a certain imitation, say a portrait of a face, brings out the character of the person by both depicting clearly certain things and emphasizing, exaggerating, and highlighting others. Thus we might agree with philosopher Nelson Goodman who has argued that resemblance is neither necessary nor sufficient for representing a subject matter. After all, when we try to create a resemblance we are always selecting, including, and excluding aspects of the subject. For instance, is the human being I am depicting a set of sub-atomic particles? A friend? A politician? A generous person? The choice of what to include and exclude is indeed a choice and an unavoidable one. Imitation implies interpretation. So perhaps the project of getting to the object or person itself is impossible and misguided to begin with.[2] In any case, here we should think of Vincent Van Gogh’s groundbreaking portraits: they do give a sense of the reality of the person; but they also introduce unrealistic colors and distorted forms to express something. In doing so, we have come to praise his work and see his imitations as unique and revelatory.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait (1887)

But if this is the case, then we see that these nuances the artist adds to the reality, these imaginative additions that add a new perspective, are usually not evaluated in terms of imitation; rather, they are seen as interesting formal innovations, new modes of expression, or new ways to help the art serve as a powerful instrument of some sort. But if this is the case then all our evaluations of imitations will end up adding elements from others theories of art—formalism, expression, and instrumental—and in doing so reveal that the imitation theory is not sufficient as a general and fundamental theory of art.

For my many other posts on aesthetics, go here.

[1] Richard Eldridge, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Art (New York: Cambridge, 2003), p. 29.

[2] See Nelson Goodman’s Languages of Art, second edition, (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1976), p. 4.