244. Life on the Railway Station: Agnes Heller on Losing and Making Homes in Postmodernity, Part 1

Introduction

Agnes Heller (1929-2019) was a Hungarian philosopher who, among many other things (see a bio here), was Hannah Arendt Professor of Philosophy at the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research for 25 years. I took four incredible classes with Agnes from 95′-99′ and continue to praise her ability to expose the meaning of seemingly impenetrable texts, her inspiring enthusiasm for the material, and the vast range of her knowledge. But if I had to point out the one thing that made her lessons so engaging, it was the way the material was explicitly linked to significant cultural changes and how these changes affect us today. She articulated and explored two closely connected changes which I found particularly intriguing: the loss of a sense of home for so many people and the fact that this loss of home is related to no longer having a world. These claims appealed to me when I was in my late twenties. I was overwhelmed by the vastness of the NYC, my lack of meaningful social relations, and the uncertainty about my abilities as a philosopher. I was having trouble envisioning a new home geographically, socially, and professionally. And this trouble appeared to be a function of me lacking a world. Some twenty five years later Heller’s views on home and world are still with me and, if anything, have become all the more fascinating and relevant as I have applied and developed them.

This three-post series aims to empower you to apply and develop them as well. In this post I begin by presenting her account of the modern and postmodern worldviews. We will see how Heller thinks postmodernism leaves us with “life on the railway station” or the state of being radically contingent beings confronted with the task of choosing ourselves. I then explore her closely related ideas of world and home in order to show how postmodernists are threatened with existential homelessness. Once these basic ideas are in place, in the next post I develop some of her suggestions for facilitating moral, beautiful, conversational, comic, and democratic relations that can reduce this homelessness. I refer to these suggestions as ways of home and world making and we will see that, once we are adequately capable of pursuing some of these ways, home can be a place we make wherever we go. This offers us hope that homemakers everywhere can integrate their worlds into one larger world which Heller refers to as a “mosaic of difference.” However, she also explores two forms of world closure in which people shut themselves up in their own world and see others as aliens to be ignored or, if this closure is evil, destroyed. The many manifestations of world closure, which include fundamentalism, racism, sexism, and totalitarianism, threaten to undermine world and home making efforts and especially democracy. So a close look at both forms of closure in the last post will be in order. Since some of her ideas can be as controversial as they are fascinating, I close with something Agnes would no doubt welcome: some questions to generate inquiry.

The Modern and Postmodern Worldviews

In order to understand Heller’s thoughts on home and world, we must first understand her distinction between modernist and postmodernist outlooks. This passage from her book A Theory of Modernity (Wiley-Blackwell, 1999) is helpful in understanding the former:

“The modernist man who was clinging to the grand narrative pretended to know what will happen to the human race in the distant future. He lived (and thought) in this distant future. He drew “knowledge” about the distant future from the story of mankind. Thus, he looked into the past as a storehouse of frozen memories, of the finally stamped and understood series of events which, out of necessity, lead to the future. The present did not count. It was an intermediary stage. The only present that existed was personal (one has to make a living). But the present-as-such has not fired the imagination” (TM, 183).

Modernists, of course, live in a temporal world and have to make practical and personal decisions with reference to the past, present, and future. But such decisions do not affect their understanding of time in a more general and fundamental sense. This deeper sense includes both an understanding of the goal towards which history is necessarily moving and the ways to best live in accordance with this goal. For example, a Christian might see the unfolding of history as a necessary progression to the second coming of Christ and believe that the means for obtaining salvation have been given in the past. The present is therefore a mere intermediary stage to an unavoidable end point. Naturally, the present may give rise to challenges that call for inquiry and decisions. A Christian might ask: how do I respond to this person in a way that best imitates Christ? But, given that the foundational narrative is understood and taken to be true, there is no decision making regarding that foundation and the guidance it provides. In this sense, then, “the present did not count.”

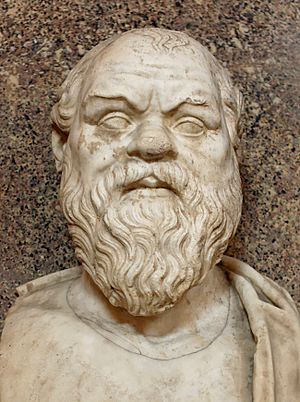

Postmodernists, however, are in the exactly opposite situation. For they live in “the absolute present tense” which means that the future beyond their horizon is unknown (TM 10). Like Socrates, they know that they know they know very little, “if anything at all” (TM, 4). Rather than experiencing history as a necessary progression, they experience history as radically contingent through and through:

Socrates

“The postmoderns do not claim to have a special, privileged position in history. They do not believe they know the future better than their ancestors ever did. (Maybe, they know it less.) They do not claim that science offers them the key to open up the future, because they are aware of the fragility of science. They think in terms of contingency; not just the contingency of the single individual (both cosmic and social), but also the contingency of historical times and ages – the contingency of their present” (TM, 10).

In her A Philosophy of History in Fragments (Wiley-Blackwell, 1993), Heller stresses that “‘contingency’ is an existential term” that denotes more than chance, the accidental, or the fact that things that can be otherwise (PHF, 1). Rather, it expresses the “shock” postmodernists experience when they realize they have been “stripped” of predetermined purposes (PHF, 4). And in Aesthetics and Modernity (Lexington, 2011) she notes that this contingency has, on the one hand, a cosmic dimension which reveals that “the belief in the pre-set telos of our earthly life” is gone and, on the other hand, a social dimension which reveals to postmoderns “the question mark that now replaces the fixed spatiality (country, city, rank) of their appointed destiny” (AM, 206). This shock of contingency will lead some to become nihilists who deny objective truth and morality. Others will go to the other extreme and become fundamentalists who claim to have access to absolute truth. Such people are “inauthentic” in their adoption of a destiny they take to be given (PHF, 243). But postmodernists choose to be authentic and keep “the wound of contingency bare” and face the challenge of critically assessing their past and future in order to figure out what to do in the present (PHF, 7). As a result, they find themselves with a heavy burden of responsibility for the present as well (TM, 183).

The lack of historical necessity in the postmodern view doesn’t mean it dispenses with the past and future as such. Rather, this “new model of contingency” incorporates both the “push” of the past and the “pull” of the future in a way that preserves radical freedom. On the one hand, past factors influence rather than necessitate and, on the other hand, future goals are “not destined from the outside but, rather, destined from the inside, by one’s own choice” (TM, 227). And this choice can be a function of “translating” external pushes into self-determined pulls. Indeed, it can be a function of translating all determining factors in a way that brings the self into existence: “The choice of the self means the choice of everything that one is: when I choose myself I choose all my determinations – I choose my drives, my infirmities, my mental abilities, my neuroses, just as I also choose myself as my self, with all of the predeterminations that define it: my age, my birthplace, my family, my religion, and so on” (TM, 227). And in choosing all our determinations “we make ourselves free” as she puts it in A Philosophy of Morals (Blackwell, 1990, p. 14). Heller, following Kierkegaard, refers to this existential choice as a “leap” which, while having access to plenty of “crutches” for guidance, is ultimately self-determined: through the leap “every life grounds itself” (TM, 14).

Life on a Railway Station

This brief overview of the modern and postmodern worldviews brings us to Heller’s intriguing metaphor of the railway station. Consider this passage:

“The postmoderns accept life on the railway station. That is, they accept living in an absolute present. They do not wait for the fast trains so that they should be rushed to their final destination. All final destinations are unmasked as harboring disaster. Thus the postmoderns claim ignorance in the matters of final destination; they accept the “provisory state,” the here and now, as the final stage – for them. The future is unknown.” (TM, 9)

Untitled (The Subway) by Mark Rothko (1937)

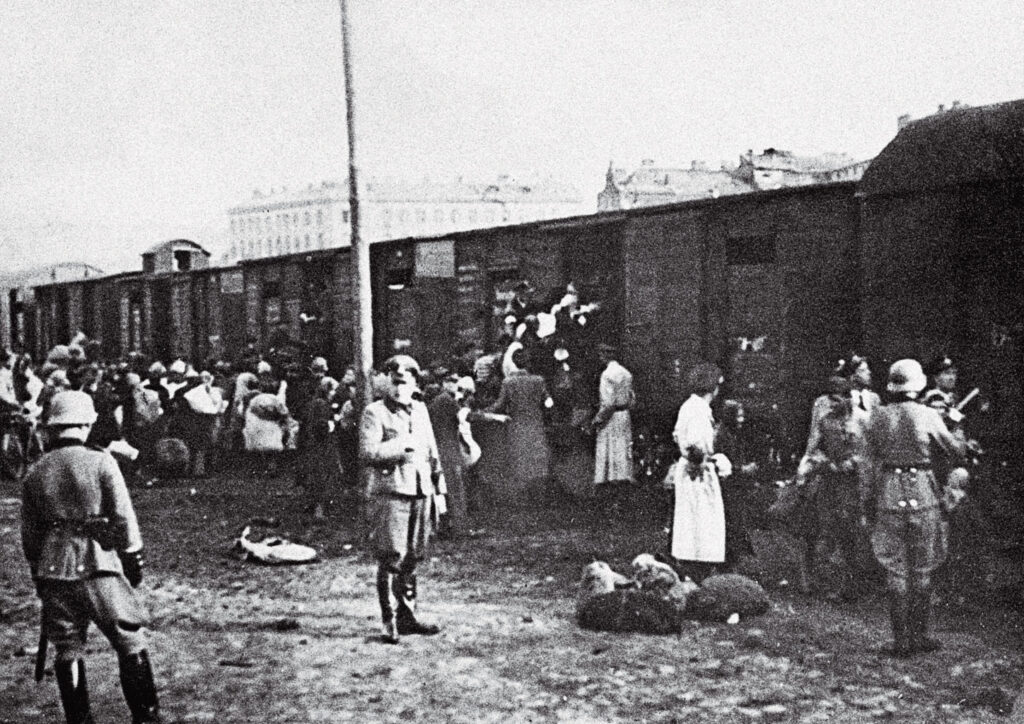

Those who embrace life on the railway station will always be asking the “fundamental questions of historicity” which are “an essential constituent of the human condition,” namely, “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” (TM, 74) As a result they can hope to guard against those journeys – she mentions journeys to Auschwitz, the arctic regions of Siberia, and the islands of the Gulag in particular – in which people are sent to a “Man-Made-Hell” which is “know by the planners, but not by the passengers” (THF, 217-18). This doesn’t mean postmodernists can’t travel from station to station. But they will always be acutely aware that their contingency offers departures rather than final destinations:

Jews being loading onto trains at the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw during the German occupation of Poland

“Men and women on the platform are already standing outside the tradition. But they are still dwelling on the soil of the city, they have not yet left, they could still stay and return. But returning, the great dream of the seafarer, is not the dream of the train-passenger; his absolute present is the moment of departure” (PHF, 220).

Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway by J. M. W. Turner (1844)

Being a traveler standing outside traditions can certainly be liberating. But it also brings with it a threat of losing one’s world and perhaps even one’s home. So let’s take a look at Heller’s meaning of these terms. We can begin to do so by considering the distinction she makes between knowing and having a world.

World and Home

According to Heller, one has a world when one spends enough time in a location to be experientially and sensually integrated into its people, language, customs, laws, and especially traditions in such a way that one can enact significant change for oneself and others: “For one “has a world” only if one can change it, not only for oneself, but also for the denizens of that world” (TM, 189). We can also know a world by grasping facts about it indirectly through books, stories, descriptions, films, art, news, and so on. Unlike the action-based criterion of having a world, knowing a world “requires the attitude of the spectator” (PHF, 228) and the translation of actual places into virtual ones through the imagination (TM, 186).

There are people who know very little about other worlds and in some cases make an effort to know as little about them as possible. But plenty investigate worlds and are open to expanding the world that they have. Heller points out that in the past, there were “representative microcosms,” such as Rome, London, and Paris, where one could go to get informed of world culture in an attempt to know as many worlds as possible and perhaps even come to have more of them. But the sheer diversity of worlds has made even these former microcosms inadequate. So many seek to fill the gap with tourism which is “not just a pastime or a way to fill the empty hours of boredom. It is also a mad attempt to fill the gap between the world that we know (about) and the world that we have” (TM, 188).

Cartoon by Otho Cushing (1871-1942) published in Life Magazine January 12, 1911.

Now the world that we have can be called a home: “Our own world is called Home. Having a world begins at home” (PHF, 229). Heller articulates many distinguishing factors of a home. Here are a few of the most important. First, home is the place which is “close” to us and this closeness can be discerned by (1) “the briefer the length (the path) of communication is, for “close persons” understand one another without words, by allusions, in an abbreviated manner – they speak shorthand” and (2) “whether the communicated message belongs to the function that a person performs in the division of positions and ranks of the social arrangement” (TM, 191). If the communication can take place without reference to such positions and ranks – if there are no “footnotes” needed – then there is more closeness than remoteness.

Saint George’s Day Festival by David Teniers the younger (1645)

Second, the sense that we are at home provides a fundamental “emotional disposition” or “framework emotion” that accounts for the presence of many other emotions including “joy, sorrow, nostalgia, intimacy, consolation, pride, and absence of others.” All these emotions include a cognitive and evaluative aspect as well. This shows how important a sense of home can be to our perception of the world and how the lack of home can lead to certain unwelcome emotions and cognitive privations (AM, 207). As Heller notes with reference to a comment by Wittgenstein, “the world of a happy man is different from the world of an unhappy man” (PHF, 240).

Third, Heller distinguishes between the spatial homes, temporal homes, and the home of high culture or, to use a phrase from Hegel she prefers, “absolute spirit.” A spatial home is marked by the same characteristics as having a world: it has a certain geographical location with a rich network of people, language, traditions, etc. A temporal home is made possible once one leaps into a self-appointed destiny that is pursued over time: “I follow my destiny on the wings of Time, and while exercising my talents, I will find my appointed home” (AM, 207). And the home of absolute spirit is the home of high culture which offers profound expressions of the human condition open to all who can appreciate them.

Finally, our experience of homes usually include commitments, norms, and obligations since every home we have entails activities of following standards, observing requirements, participating in a language game, and making evaluations. One might think the experience of, say, being at home in nature would be commitment free. But “even the song of the nightingale and the shade of the chestnut tree oblige, for we cannot take it for granted that they will be here tomorrow” (AM, 221).

The Chestnut Tree at Saint-Mammes by Alfred Sisley (1880)

Naturally, we are all born into a world not the world which is “the world people normally know about”, i.e., the world which is the totality of worlds (PHF, 228). But it is possible to expand into other worlds and extend our home since “Expanding the world one already has is to expand home.” But, given the time and experience it takes to have a world, we cannot have “too many, and certainly not all of them” (PHF, 229).

Homelessness and its Consequences

The process of knowing about other worlds need not threaten the world we have. In fact, this knowledge can help us enrich and evaluate it. But in some cases the imaginative exploration of worlds ends up alienating us from our own traditions, beliefs, people, laws, religion, and so on to such an extent that we lose a sense of home. Heller points out that there are “united tourists” who are estranged even from their native worlds. These tourists enter into a new world of people who, in constantly moving around the globe, share certain experiences (of restaurant chains, hotels, TV shows, consumer goods, etc.) but lack the traditions that accompany having a world. In this case there is no world center and thus no home: “If the world is many centered, so that no center has a privileged position (in the world that we have), there is “multiculturalism,” for all centers are de-centering identities but, in all likelihood, men and women are nowhere really “at home”” (TM, 191). This loss of home certainly applies to those of us who live on the railway station since, as we saw above, those “on the platform are already standing outside the tradition.” Indeed, since “we are born contingent – and aware of our contingency – we are strangers, aliens, wherever we are born” (TM, 194).

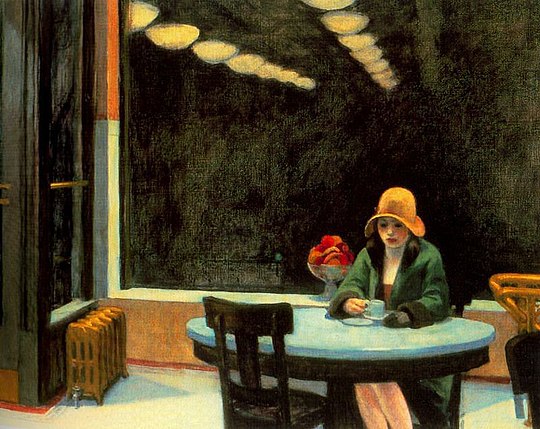

Automat by Edward Hopper (1927)

This homelessness has many troubling consequences. For example, it can lead people to treat things as expendendable since the care we have for things is typically a function of our home-centered relations to them. Rather than being integrated in a network of inherently valuable objects, one only establishes temporary functional relations that can easily be dropped and replaced. Heller notes that a “watch was still a family heirloom a century ago; grandsons inherited it from their ancestors. Today, one buys a new watch every year…The modern world is a cemetery of things that had been used but not used up, just replaced and thrown away” (PHF, 231). This expendability leaves us with the “ugliness, dirt, and stink” of the “necropolis of things” which seem to have never been a part of any world (PHF, 235).

Unfortunately, cosmic contingency extends this expendability to people as well: “The threat of cosmic contingency is coeval with the emergence of the modern mechanistic view of the universe, with the substitution of the infinite matter of the immense necropolis for the living and ensouled divine Cosmos, and of the brave new world where the single person is just a Zero, where he or she does not count, and where God is dead, for the Eternal Governance is lost” (TM, 6). Human expendability can manifest itself on a massive scale as we know from the nightmares of totalitarianism, widespread alienated labor, unjust war, genocide, sexual trafficking, slavery, and so on.

Finally, threatening psychological effects emerge in the “uncanny space” of homelessness (AM, 206). In her book The Time is Out of Joint: Shakespeare as Political Philosopher (Lexington, 2002), Heller distinguishes between three types of identity disturbance Shakespeare illuminates for us: problematizations, disorder, and world loss (TJ, 36). World loss is about “being stripped naked,” that is, realizing the radical existential contingency of things and that we are just a throw of the dice (TJ, 52). This “collapse of a world” can lead to a collapse of the ego. She exemplifies this point with reference to King Lear since for the king “losing himself means losing the world” (TJ, 55). Those who experience world loss in this fashion run the risk of being seen as mad by those in one’s previous inhabited world (TJ, 56). This is certainly the case with Lear. And the perception that one is mad threatens to make one actually mad. There is also plenty of anxiety, melancholy, and depression associated with homesickness or a “longing to go back to the bosom of the protection of the Certainty, the Absolute” (TM, 194).

King Lear and the Fool in the Storm, Act III Scene 2 from King Lear by Louis Boulanger (1836)

Is there any way to deal with these threats to our well-being and even sanity? There certainly is and in part two (go here) we will consider Heller’s suggestions for making homes and worlds while living on a railway station.

© Dwight Goodyear 2025